Iraq after ISIL: Tikrit and Surrounding Areas

Shi’a PMF and local tribal Sunni Arab hashd hold off ISIL on the frontline in Dour, but their strong presence, and periodic outbreaks of violence and looting challenge ISF’s ability to maintain rule of law in Salah ad-Din’s capital area.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

The capital of Salah ad-Din governorate and birthplace of Saddam Hussein, Tikrit has long been an important Sunni Arab power center. However, when Tikrit and the nearby areas of al-Alam and Dour district (also discussed in this summary) were taken by ISIL, Iraqi forces collapsed, and Shi’a PMF forces were a leading part of the force that recaptured these areas in March and April 2015. Since then, Shi’a PMF forces have continued to play a strong role in the governorate. They have a sizeable force presence and local bases in the governorate, and local Sunni tribal forces are affiliated with and working under them in many areas. Although the Iraqi government and Iraqi federal and local forces are technically in control, Shi’a PMF act autonomously in practice and are unchecked and uncontrolled by local authorities and Iraqi forces.

The PMF dynamics in the Tikrit area are heavily intertwined with the larger political competition in Salah ad-Din and with local tribal rivalries, which only heightens political instability. In addition, although these forces were mobilized to defend and stabilize, both the larger PMF forces from outside Salah ad-Din and local tribal PMF forces have been involved in revenge attacks, abuses of the local population, and extrajudicial detention. These acts of violence, combined with the overall fractured control that results from the presence of so many security actors, significantly undermine the rule of law and stability in Salah ad-Din.

ISIL Capture and the Camp Speicher Massacre

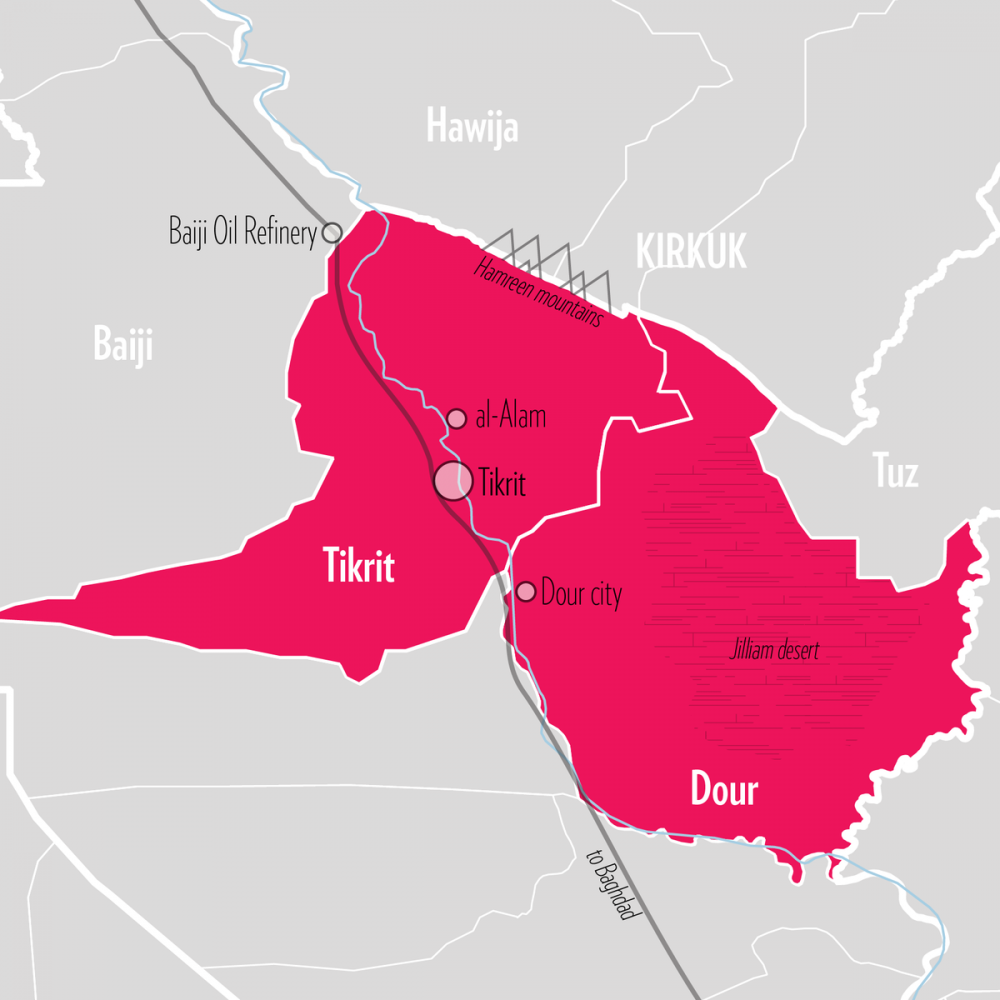

Tikrit is the capital and main population center of Salah ad-Din governorate with an estimated population of over 200,000.2 This research summary will also discuss some of the LHSF dynamics in two nearby areas, Dour district and al-Alam subdistrict, which each have an estimated 60,000 and 30,000 residents, respectively.3 All three are predominantly Sunni Muslim. Even the more urbanized, central area of Tikrit, called Tikrit Markaz, is 90% Sunni Muslim.4

The reason this summary stretches across district and subdistrict boundaries is that the trends and dynamics in these nearby areas often overlap and interact. The three sites run along the main road that stretches from Ninewa governorate down to Baghdad: first al-Alam to the north, then Tikrit, and finally Dour. Many officials from al-Alam are active in Tikrit, and vice versa. The main external security threat facing Tikrit and al-Alam emanates from the Jilliam Desert frontline, which runs across the territory of Dour district. As a result, the security dynamics and actors across all three areas are interlinked. In addition, common trends have emerged in terms of the LHSFs and their relationship with local communities and officials.

Key Facts: Tikrit & Surrounding Areas

Population: 200,000

Ethnic Composition: 90% Sunni Muslim

Date Officially Retaken: March 14, 2015 (al-Alam, Dour); April 17, 2015 (Tikrit)

Ground Forces Engaged: Iraqi Security Forces, Shi’a PMF, Federal Police

Overall Control: Officially under Iraqi gov’t control, but unconstrained and significant Shi’a PMF activity

LHSFs Present: Badr, AAH, and Hezbollah, range of Sunni tribal PMF

Key Issues:

- Shi’a PMF competition for control, with unchecked abuses

- Acts of revenge and retaliation escalating local conflicts

- Reconstruction from initial destruction and looting

Shortly after the fall of Mosul, on June 10, 2014, ISIL forces continued pushing west and south, capturing Hawija in Kirkuk and a significant swath of territory across Salah ad-Din. By the evening of June 11, 2014, they had seized Tikrit and then Dour. Many of the Iraqi army and police had fled, so resistance was minimal. Some of the population, frustrated at harassment or discrimination under the previous al-Maliki government, appeared to even welcome the change. Locals in Dour told Human Rights Watch (HRW) that the population had felt alienated by the Shi’a‑dominated Iraqi government under Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and had believed ISIL’s narrative of supporting them against Shi’a oppression.5 (A backgrounder on recent historical event relevant to this study discusses the conditions under the al-Maliki government and the effect on LHSFs to a greater extent).

At roughly the same time, ISIL fighters surged north and seized an Iraqi Army base just north of Tikrit, called Camp Speicher. On June 12, they executed several hundred Shi’a recruits based there and distributed a propaganda video publicizing what came to be known as the “Camp Speicher massacre.”6 ISIL claimed they killed 1,700 men, but a HRW investigation estimated that the number was closer to between 560 and 770 men.7 The killings had a definite sectarian bent to them, with news reports suggesting the Shi’a recruits were separated from their Sunni comrades before being executed; some sources suggested that local Sunni tribes took part in the massacre or generally supported ISIL, which caused tensions with other tribes in the region.8 The incident enraged the Shi’a community and was seen as a driving factor behind an immediate and harsh Shi’a PMF intervention into Salah ad-Din, including acts of retaliation and revenge against Sunni residents (to be discussed shortly).9

Locals in al-Alam said there was greater local resistance from tribes in al-Alam, many of whom had long been engaged in local government. However, following heavy casualties, including the loss of civilian family members, and no support forthcoming from the Iraqi government, on June 24, 2014, al-Alam tribes concluded an agreement with ISIL to cease fighting and relinquished control to ISIL.

During their occupation of Tikrit and its surrounding areas, ISIL introduced their version of Sharia law, and executed or meted out harsh punishment against those who had worked for the Iraqi forces or the government, or who disobeyed their rules.10 Higher-level police fled with the army as ISIL advanced, but many local police and officials, particularly in the more rural areas surrounding Tikrit (e.g., in Dour), stayed behind and were executed or punished. In Dour, ISIL detained some 40 people while there, most of whom were police. Some were killed publicly, and others were taken away, presumably to other ISIL strongholds, and never returned. ISIL also reportedly destroyed most of the police stations and some detention facilities, according to locals and officials in these areas, but residents report the group caused a relatively minor level of damage to homes during their occupation. Locals in Dour estimated the level of damage at perhaps a dozen homes, and in al-Alam, which is more of a stronghold for local government authorities, an estimated 50 homes were damaged under ISIL.

The mayor of Tikrit estimated that in the initial weeks of ISIL’s occupation, 70 percent of the city of Tikrit fled. Locals who were in al-Alam and Dour, outside Tikrit, said the ISIL capture sparked some initial displacement, but that it was more of a gradual process, with residents continually fleeing in small numbers throughout the ISIL occupation. The first to leave were members of the Iraqi Army, local police, and government officials and their families. As ISIL began engaging in wider detentions and abuses, more and more of the population fled.

Retaking Tikrit and Surrounding Areas

Repeated efforts to retake Tikrit, which began as early as the end of June 2014, failed, and major assaults in August and December 2014 were rebuffed.11 A coalition that was primarily made up of Iraqi forces and Shi’a PMF groups, significantly supported and advised by Iranian forces, reassembled and began a major assault in March 2015.12 The total number of fighters was estimated between 20,000 and 30,000.13 A much smaller number of local Sunni tribal forces from the captured areas, including Dour, al-Alam, and Tikrit, also joined the larger PMF forces, with many formally registering under the PMF umbrella in Baghdad.

Media reports and local sources suggest that Dour and al-Alam came under government control between March 5 and March 9, 2015, with a full declaration that they were liberated on March 14, 2015. It would take another month of intensive fighting until Tikrit was officially declared liberated on April 17, 2015.

The primary Iraqi forces engaged included the Iraqi Army, Special Forces, and Federal Police, supported by the Badr Organization, Kata’ib Hezbollah (the Hezbollah Brigades), the Imam Ali brigades, and AAH. Although the Shi’a PMF played a significant role in the early part of the Tikrit offensive, in late March 2015 they were officially pulled back due to US objections. Kata’ib Hezbollah are officially on the US terrorism watch list, and several former leaders of AAH were designated global terrorists.14 The US refused to work with the PMF militias and withheld critical aerial support until they were withdrawn.15 The results of this objection on the ground were mixed. Spokesmen for several militias stated that they chose to withdraw from Tikrit in protest of the US involvement,16 and conflicting reports suggest that many PMF groups continued to fight, or rejoined the fighting later, regardless of their official withdrawal.17 They were certainly present and visibly active in Tikrit, al-Alam, and Dour in the immediate aftermath of the fighting.

The clearing operations were shared among all parts of the liberating force, with different parts of the Iraqi forces and PMF forces appearing to divide tasks and take different areas (down to a neighborhood level of specificity) on an ad hoc basis. This makes it difficult to say precisely which force led in clearing, for example, Dour, al-Alam, or parts of Tikrit specifically. One local journalist, who had interviewed military and civilian sources present during the fighting, suggested that the Iraqi Special Forces took on most of the direct fighting and that the Shi’a PMF followed closely on their heels (often claiming the victory for themselves), but accounts differ from one area to another. Locals reported that Federal Police were active in taking control of Dour and al-Alam immediately after liberation.

The Aftermath: Mass Displacement, Looting, and Destruction

The retaking of Tikrit and surrounding areas sparked mass displacement, to the level of nearly 100 percent of the civilian population at periods of peak fighting. HRW reported that by February 2015, most of Tikrit’s population had fled – for Samarra, Baghdad, Kirkuk, or Iraqi Kurdistan – with only around 10 percent remaining in the city.18 A REACH report concluded that no residents were left in Tikrit city at the end of the conflict in April 2015.19 Locals who were in the areas said displacement was total but that the patterns and locations of displacement shifted frequently; residents fled from one area to another as the frontline moved and often returned to their homes when it became possible. One local in Dour said that as Iraqi government-led forces advanced on Dour from the south, many families fled north into Tikrit, but when the military advanced on Tikrit, Dour civilians reversed course and went the other way. “They were fleeing the fighting and trying to get behind the front lines, to get safe, in whatever way was the easiest way possible.”

In addition to avoiding the open fighting, many civilians fled in this period because they wished to avoid being associated with ISIL and feared retaliation from incoming Shi’a forces. “The local Sunni population,” in the words of Al-Jazeera political analyst Marwan Bishara, seemed, “no less frightened of the Shi’a militias than they are of ISIL.”20 A representative of the Tikrit police from al-Alam stated that people who stayed in the area for a longer time were presumed to have joined, or collaborated with, ISIL and were detained on those grounds.21

Given Tikrit’s legacy as the birthplace of Saddam Hussein and the significant number of former Baathists who joined ISIL,22 the fighting in Tikrit was always likely to have borne a sectarian tinge. However, the Camp Speicher massacre inflamed these tensions, and the Shi’a PMF (as well as some Shi’a members of Iraqi forces) came to Tikrit looking for revenge against these Sunni-perpetrated abuses.23 The local population largely bore the brunt of this anger. Dour and al-Alam were taken first, and residents reported that although the overall damage was very small – about 10 percent of homes in each – the damage to infrastructure was predominantly caused by PMF forces and was either facilitated or not prevented by the Federal Police, who were nominally in control. According to one local report, after the Federal Police (predominantly) cleared Dour, Kata’ib Hezbollah took control for several days (from shortly after Dour was liberated through March 16), and the looting and destruction started. A HRW analysis of satellite imagery suggested that large sections of Dour town were damaged or destroyed between March 8 and 9, and stated that locals interviewed blamed the destruction on Kata’ib Hezbollah.24 HRW found evidence of 540 destroyed homes, 430 torched houses, and 95 damaged shops.25 Although most residents had fled by this point, there are also allegations of Hezbollah fighters rounding up nearby IDPs. One Dour resident said that many of the families in the district fled populated areas into the Jilliam Desert area, on the other side of the district. Upon taking control of Dour, Hezbollah fighters came to this area and detained 300 men, aged 14 to 50, only 11 of whom had been confirmed as released in summer 2017. There were similar reports of looting, detentions, and destruction in al-Alam, presumably perpetrated by both the PMF and Federal Police, which were the only forces in the area immediately after its liberation.

Although much of the damage in al-Alam and Dour was blamed on Shi’a PMF, there are also some allegations against the Sunni tribal PMF. According to HRW research, the local tribal council in al-Alam stated that a local Sunni tribal PMF, working with the Shi’a PMF, destroyed the homes of suspected ISIL collaborators.26 Airstrikes also caused some damage in both al-Alam and Dour, but it was relatively limited. One local Dour resident estimated that airstrikes had damaged no more than a dozen houses in the main populated areas.

Looting and Destruction in Tikrit

While the damage caused in the recapture of al-Alam and Dour was significant, the looting in Tikrit was more extensive and had much greater political consequences. HRW found that Shi’a PMF looted, torched, and blew up between 160 and 200 civilian housing and buildings in Tikrit.27 They also found that the PMF unlawfully detained around 200 men and boys. The whereabouts of 160 of these men and boys was still unknown at the time of HRW’s research. Officials, residents, and Reuters correspondents also witnessed several extrajudicial killings by the Badr Brigades, AAH, and the Federal Police.28

The looting of Tikrit caused a public uproar; even Prime Minister al-Abadi spoke out against it and noted that some 168 homes or properties had been damaged. On April 4, 2015, al-Abadi met with Salah ad-Din province officials, and they issued a joint decision for all PMF fighters to leave Tikrit, placing the city in the hands of the federal and local police.29 The looting of Tikrit and the political backlash was a major reason given for holding back the PMF forces in the liberation of Mosul.

The local narrative of what happened in Tikrit differs somewhat from the larger political narrative at the time. Local officials interviewed for this study confirmed that hundreds of homes and shops were looted but estimated that the damage was relatively targeted and contained. Both a provincial council member and a leader of the Sheikh’s council estimated that the level of damage did not exceed 20 percent of public and private properties and that it predominantly affected those who had been affiliated with ISIL. Locals also tended to split the blame, ascribing some of the damage to Shi’a PMF acting out of sectarian motivations and in retaliation for Camp Speicher, but much more of it to the local Sunni tribal PMF affiliated with the Shi’a PMF.30 As evidence, they pointed to the fact that looting and destruction was quite targeted against rival tribes whom the Sunni PMF forces blamed for supporting ISIL and, in many cases, who had directly targeted their properties and family members when ISIL was in control.

Fractured Control and Shi’a PMF Dynamics

Although Tikrit and its surrounding areas have been under Iraqi government and local governorate control since April 2015, this control is divided and shaky. With the main frontline with ISIL only 15 kilometers away at the Jilliam Desert in Dour, Tikrit and surrounding areas experienced frequent attacks throughout 2015. Another major offensive in March 2016 pushed this frontline back somewhat, relieving security pressures on Tikrit and Samarra and shifting the fighting to Shirqat. However, even in 2017, ISIL sleeper attacks and threats in Tikrit continued. Some analysts speculated that Tikrit was so under-manned that it was still vulnerable to being re-taken by ISIL.

ISIL is far from the only source of instability in the Tikrit area or the governorate as a whole. Perhaps even more concerning is the overall effect of competing security actors in Salah ad-Din on rule of law and stability. Although the Shi’a PMF forces are not formally in control and are often not visible, they rival Iraqi official forces for control, and some interviewees argued that they are “the true power holders” in Salah ad-Din. The most frequently mentioned and influential Shi’a PMF in the Tikrit, Dour, and al-Alam areas at the time of writing were Badr, AAH, and Hezbollah (for more on these groups, please see the Annex of quick facts on key LHSF groups).31 The Khorasani Brigades are also active in the nearby area. Many of the forces for these groups are based outside the main population areas – for example, Badr in the Himreen mountains on the border between Tikrit and Kirkuk governorate. However, through free access across the governorate and local forces affiliated with them, these PMF forces retain a substantial influence on the Tikrit area.

Interviewees, including governorate officials, said that the Shi’a PMF follow their own orders and do not defer to local authorities. The degree of PMF forces’ autonomy is so great that they even maintain their own detention sites in Salah ad-Din, in Baiji, Samarra, Balad, and Hamra. Member of Parliament Badr al-Fahal confirmed this fact publicly on television (and later said he received threats as a result of his disclosure). Given their significant force size and political autonomy, local governorate authorities are not able to control or check PMF behavior, even where it violates the law. As an example of the power dynamics, local officials cited conflicts between the Shi’a PMF and Iraqi forces, of Shi’a PMF disregarding Iraqi officials at checkpoints, and even of clashes between both forces. As an example, one local journalist cited an incident in the summer of 2016, in which – after an initial disagreement – members of Kata’ib Hezbollah detained members of Iraqi SWAT forces stationed in Tikrit. To resolve the issue and have their members released, the involved Iraqi and local authorities eventually had to back down from their position. Describing overall conditions in the governorate and local areas, as one provincial council member noted: “The Iraqi police are available [and] try to apply the rule of law, but…the existence of different types of forces and sometimes clashes with [these forces] weakens their performance.”

Most of the allegations of misconduct or abusive behavior – most frequently kidnapping and detention of locals and looting and destruction of property – were attributed to Hezbollah and AAH. Local officials and tribal elders generally agreed that most Badr fighters were law-abiding and that the Badr Organization (both higher-level authorities and fighters) was more cooperative with and supportive of locals than other PMF groups, but still reported to their own command.

The contest for authority between the Shi’a PMF and local authorities is enmeshed in local political rivalries. At one pole is Governor Ahmed Abdullah al‑J’bouri, who most recently took up the governorship in April 2016 but had previously served in the same position in 2009 and 2013. The governor is generally opposed to PMF engagement in the governorate. However, though influential and stronger than other governors (i.e., in Ninewa), he is not able to prevent or contain their interference in the territory because the Shi’a PMF, in addition to their large numbers, weaponry, and entrenched positions, are politically supported by Governor J’bouri’s main rival, Yassin al‑J’bouri. The son of another prominent Sunni leader, Meshaan Al‑J’bouri, Yassin also controls his own Sunni PMF, predominantly from Shirqat.32

The fact that a prominent Sunni tribal leader would back Shi’a PMF to be active in his own governorate seems at odds with the more antagonistic rivalry that characterizes Sunni-Shi’a dynamics in much of the liberated areas. However, local analysts suggest that this may be a case of common enemies banding together. As one framed it, “Whatever is necessary to create chaos and make the area unstable is in the interests of both Yassin and the Shi’a PMF.” Several key informants interviewed suggested that the outcome of the ongoing competition between these two rivals would determine role the PMF would continue to play in Salah ad-Din in the future, and the overall level of stability. There were also significant concerns that these competing PMF groups, both local and Shi’a, could influence future political control and the dynamics of the upcoming elections. Several locals interviewed worried that the Shi’a PMF in the governorate could tip election results toward their close local ally, Yassin al‑J’bouri. As one local politician argued, “Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis [a key PMF leader] has a strong relationship with Meshaan al‑J’bouri and his son Yassin, and they all work against Abu Mazin (the governor). The next elections will be under their control, and they will choose whomever they wish. The winners will be one of their allies.”

Overall, interviewed local tribal and community leaders shared a great degree of mistrust in the Shi’a PMF, particularly AAH and Hezbollah, and viewed their intervention in the governorate as the most significant source of instability.33 One local official reflected the sentiments of those interviewed, saying, “The hashd [the Shi’a PMF] have played two roles in the cities they entered: one is positive, when they helped the Iraqi forces and the tribes to liberate their cities, and the other is bad, when some bad individuals accompanied them and perpetrated abuses. They tried to create problems on some occasions. They have looted some public places and private ones like the oil refineries.” While most cited Shi’a PMF abuses, some of the mistrust of Shi’a PMF appeared to be as much about cultural and political divisions as actual incidents of abuse; several interlocutors said that the Shi’a PMF were outsiders, with a different background and culture, who did not deal easily with local tribal culture and customs. Plus, while there were frequent reports of PMF violence, according to locals, some of this violence was actually perpetrated by Sunni forces working under the PMF, like the looting in Tikrit, rather than to Shi’a PMF themselves. The next section will discuss the Sunni-Shi’a PMF dynamics and how this relationship might influence incidents of violence.

Sunni Tribal PMF

Another layer of complexity in the security landscape lies in the role played by local Sunni tribal forces. Although these local tribal forces are a small part of the overall force – with some estimates that they number no more than 1,200 in the governorate as a whole34 – they can extend PMF influence (or government influence) over local areas. In addition, because they are embedded in tribal dynamics and conflicts, their engagement in local security roles may sharpen existing local divisions, making their impact more significant than their small numbers would suggest.

As ISIL swept through Salah ad-Din, it played into existing tribal divisions and rivalries, with some tribes directly supporting and joining ISIL forces, and other, pro-government leaning tribes opposing them. Many of those opposing ISIL had participated in local government, been members of the Iraqi forces or local police, or had joined the US-backed Sunni Awakening against ISIL’s predecessor, Al Qaeda in Iraq, in years prior – all of which would put them, their families, and property at risk of direct ISIL retaliation. As ISIL took control across Salah ad-Din, many of these pro-government Sunni tribal leaders fled with the retreating Iraqi forces and re-constituted local, tribal defense forces under the then-newly created PMF umbrella.

Although Sunni tribal leaders in many cases took the decision to join in popular mobilization independently, all of those interviewed confirmed that once they joined the Shi’a‑led PMF forces, they would then come under or be affiliated with one of the larger Shi’a PMF in practice. Once a member of the PMF, the much smaller, tribal PMF would depend on Shi’a PMF resources and salary. Even if they desired greater independence, they are too weak to directly challenge them in any given area and would not be protected by the government.

How these local Sunni PMF became affiliated with different Shi’a PMF varied on a case-by-case basis. In some cases, there appears to have been an informal assignment process once these groups registered in Baghdad, and, in other cases, Badr and AAH directly recruited local tribal forces in Salah ad-Din as they entered or cleared areas. Illustrating some of these trends, Khalid al-Gibara, a former leader of the local Sunni tribal PMF force in al-Alam that calls itself the Sons of Alam, described how his forces formed. He said that when ISIL captured al-Alam, he and many of his tribal family members had fled to Samarra, beyond the group’s control. Al-Gibara reached out to a personal contact, someone affiliated with AAH, to register his al-Alam tribal forces under the PMF. In addition to making his initial connection through AAH, al-Gibara said that financial payments and other supporting weaponry and supplies arrive from Baghdad irregularly. As a result, to effectively establish his forces, he had to affiliate with a larger PMF force – in this case, AAH.

The mobilization of the oldest and most operational of the Sunni PMF in ad-Dour, the Shammari brigade (drawn from Shammar tribesmen), followed a different pattern. Leaders of the local Shammar tribe were called to Baghdad in 2015 specifically to ask them to form a local force, which would work on the ground with both Badr and AAH. This ad hoc formation and assignment process continued as of the time of writing. In late Spring 2017, a new Sunni PMF force was started by a local Dour Sunni leader based in Baghdad, and was specifically created to act as auxiliaries to Khorasani brigades in the area.

The number of distinct Sunni PMF units in an area, the strength of these individual units, and the role they play varies considerably and is continually evolving. In addition to al-Gibara’s AAH-affiliated force in al-Alam, there is at least one other prominent Sunni PMF in al-Alam, under the leadership of a tribal leader known as Masa’ab al-Fahal. It was stood up shortly after ISIL’s capture of al-Alam in August 2014, and although it initially worked closely with the Badr organization, in 2017 it began to work more directly with ISF and local police in al-Alam, as Badr and other PMF forces’ direct intervention and activities in al-Alam and Tikrit waned (al-Gibara’s unit has also reportedly begun to affiliate more closely with local authorities than AAH for similar reasons).

In Dour, at least four distinct Sunni PMF units were operative as of the time of writing:

- The Shammari Brigade noted above was the most advanced and supported the 9th Brigade of the Badr Organization in their operations on the frontline along the Jilliam Desert in Dour. While not an advanced security task, it certainly placed them closer to the frontline and active fighting than many other tribal forces, which are maintaining checkpoints in liberated and relatively stable areas (for example, in places like Qayyara in Ninewa). The Shammari Brigade also was known to coordinate with the Khorasani Brigade, which was operating out of the Hamreen mountains, although they did not report directly to them.

- Separate from the Shammari forces, another tribal force was established shortly after Dour was captured by ISIL. Since liberation, it has mostly been active in Dour city, and assigned to primarily checkpoint and patrol duties within Dour city and at the entry points to other districts. They have worked most closely with the local police and authorities but, given Badr’s influence in Dour, also sometimes coordinated activities with them.

- The exact role that would be played by the Dour Khorasani-affiliated brigade noted above was not yet defined, as most of the forces were still undergoing training at the time of writing. However, the Khorasani brigades have so far engaged primarily in combat activities in Salah ad-Din, and kept a distance from any hold or stabilization role, suggesting that any auxiliary force would be engaged more in a fighting support role than in manning checkpoints, and would likely be operative in a wider area of operations than just their local area.

- The last and newest group within Dour had only been established in July 2017, and its numbers were still growing at the time of writing. It was not clear at the time what their exact role in security dynamics and affiliation would be.

Although dependent on Shi’a PMF for protection and resources, the local Sunni forces tended to have a different agenda than the Shi’a PMF and no natural allegiance to these outside forces. Nearly all tribal leaders interviewed expressed skepticism about the Shi’a PMF’s motivations and argued for a return to full government control. Al-Gibara, who had recently handed over leadership of his group to another commander in order to resume his normal job, said that he and his fighters did not always agree with AAH’s behavior and conduct toward locals. He said they had joined the PMF to liberate and defend their homes, and that the reason that his and other PMFs had begun to distance themselves from Shi’a PMF in 2017 was because of their different interests.

The tribal force engagement in Tikrit has manifested differently than in al-Alam and Dour, and has been dominated more by tribal forces originating from outside Tikrit than by home-grown forces. There is reportedly a relatively new, Tikrit-specific PMF unit that is run by Omar Thamir Sultan, whose father was an officer under the last regime, and draws fighters from different parts of Salah ad-Din. However, there was sparse information about the role of this recently formed and very small force and its affiliation.

More prominently, in the year following liberation, there were frequent reports of Sunni PMF from other areas periodically residing in Tikrit. For example, the Knights of J’bour (a group that includes J’bouri tribesmen from Ninewa and Salah ad-Din) and the Shirqat PMFs under Yassin al‑J’bouri might support the Iraqi army or the PMF when fighting in frontline areas, but then reside in Tikrit outside active fighting periods. The additional presence of these tribal forces has only contributed to the overall number of armed groups in Tikrit, making it more difficult to control security and limit lawlessness. Sunni PMF from other areas have been directly connected to some of the violence in Tikrit. As noted earlier, locals attribute much of the looting and property destruction in Tikrit at the time of its liberation to Sunni tribal PMF fighters who were affiliated with the Shi’a PMF but essentially out to settle their own scores. Many attributed the destruction to Yassin al‑J’bouri’s Shirqat tribal forces.

There are mixed views on the degree of Shi’a PMF culpability in Sunni abuses. While Sunni tribal forces’ acts of revenge were undoubtedly self-motivated, they also frequently served Shi’a PMF interests. Many argue that Sunni PMF, like Yassin’s Shirqat brigade, could not act so freely and with impunity were it not for the protection of their larger Shi’a PMF backers. One local analyst framed it as a quid pro quo between the Shi’a PMF and the Sunni tribal forces affiliated with them – in the case of the Tikrit looting, Sunni tribal forces got to exact revenge on local tribal rivals who had supported ISIL and attacked their families only months before. By supporting the Sunni tribal forces in doing this, Shi’a PMF also got their revenge for the Camp Speicher massacre without violating the official ban on their presence in the city (following US demands that Shi’a PMF withdraw), and this revenge would have a Sunni face on it.

However, while some see Shi’a PMF as instigating (or at least enabling) local violence, other analysts have suggested that in many cases Shi’a PMF are the ones playing a limited role in inter-tribal violence. One Baghdad-based Iraqi analyst suggested that the level of inter-tribal violence in Sunni tribal areas like Salah ad-Din is so high that Shi’a PMF leaders, notably Hadi al-Amri and Hezbollah’s Al-Muhandis, frequently act as neutral mediators to halt the violence, and negotiate ceasefires or call off local tribal forces.

Attitudes Toward and Impact of Local and National PMF Actors

The looting and lawlessness perpetrated by tribal PMFs in Tikrit and other areas begets the much larger question of how these PMF groups (both Shia and Sunni) are impacting stability and the restoration of everyday life and regular rule of law in the Tikrit area. Most interviewees argued that the behavior of PMF was causing nearly as many problems as they had addressed in eliminating ISIL. Nearly all the Sunni tribal interviewees and local residents, described known abuses by the Shi’a PMF in their areas: most commonly the looting in Tikrit and Baiji, as well as regular unlawful detentions and kidnappings and other incidents of abuse against local citizens and their property. However, while most local actors were more critical of Shi’a PMF than Sunni PMF, the research uncovered equally significant levels of Sunni PMF abuses and property destruction, as occurred with the largely Sunni PMF looting of Tikrit. The collective result of these Sunni and Shi’a PMF abuses, the impunity for any unlawful acts, and the divisions in security control, was an extremely fragile rule of law situation in Salah ad-Din.

PMF dynamics have also strongly influenced the rate of return, another metric of whether the situation in Salah ad-Din is on its way to ‘normal.’ Although overall returns have been high in the Tikrit area – between 80 and 90 percent – those not returning are strongly deterred from doing so by the presence of the different PMF actors.35 Local interviews and other organizations’ studies on obstacles to return suggest that there is a distinct pattern, in three areas, in which members of tribes affiliated with ISIL do not return, and fear retaliation from the PMF groups in control. In IOM’s survey of families from Tikrit city center who had not returned (most of whom were predominantly from this tribal background) 11 percent mentioned fear of security actors as the main reason they had not returned, while 26 percent mentioned fear of reprisals or acts of violence.36 Seventy-six percent of these IDPs also reported that they were “very dissatisfied” with the role “militias” are playing in Tikrit.37 Although the IOM study did not extend to Dour and al-Alam, those interviewed suggested a similar dynamic in these outlying areas – they said that those who had not returned mostly came from tribes or families that were strongly associated with ISIL, and they would not return because they faced threats of retaliation.

While the PMF dynamics certainly inhibit return, the obstacles of return are much broader and deeper. Lack of return has not only been a question of fear of reprisals, but directly blocked access partly by PMF but also local government authorities and communities. There certainly have been fewer overall returns in PMF controlled areas, as discussed in the research summary on Baiji, than in areas like Tikrit or al-Alam where there is full government control. However, the exclusion of certain groups – notably those considered to be “ISIL families” – has been a joint effort of governorate and local authorities, often enforced by PMF actors, both Shi’a and Sunni, with the support of local communities. In August 2016, the Salah al-Din governorate council issued a decree stating that anyone found to have been complicit or affiliated with ISIL had no right to return to the governorate.38 There are mixed reports of whether this decree has actually been implemented. However, it is widely known and interviews and other research studies suggest it has been the basis for local authorities or PMF forces at checkpoints and vetting centers to deny IDPs the right to return, and for members of the local community to destroy the property of those associated with ISIL.39

Local tribes have also established a high bar for these ISIL families to be accepted back into communities. One prominent sheikh and provincial council member, Sheikh Khamis, noted a tribal agreement in al-Alam to pardon tribes that had supported ISIL and integrate their members back into the community if they: 1) openly declared that their members who had joined ISIL had been wrong; 2) they rejected contact with them and refused to support them; and, 3) demolished their homes. ISIL families who did this (including by cutting off contact with, or support for, sons and fathers who were ISIL fighters) would be allowed back into the community, according to this agreement. However, Khamis noted that few ISIL families had taken this pathway to return because they mistrusted the local community’s guarantees and feared for the safety of male family members who had some affiliation with the group but had not yet been detained.

Given the unstable security situation, it would be hard to describe the situation in the Tikrit area as fully normalized. The ongoing political competition – which was all the more volatile due to one side (Yassin’s) affiliation with strong and unchecked Shi’a and Sunni PMF forces – foreshadowed a rocky political and security situation for the near future. Overall, the divided security landscape, between a range of Iraqi, Shi’a PMF, and local tribal forces, makes it difficult for any one actor – particularly the local Salah ad-Din authorities – to control security in the governorate and provide for an even rule of law. Most locals and analysts interviewed said that the divided security architecture was not able to enforce law and order on a daily basis to protect civilians, and would be unable to withstand future attacks, or contain instability produced by future political competition.

In the future, most local officials and community leaders favor returning full control to government actors and disbanding, or removing, PMFs from major security responsibilities in the governorate. Those interviewed argued that the presence of multiple, competing armed groups was unhelpful and, similar to Sunni leaders in Ninewa, most expressed a desire to have the Iraqi government resume full control of security. As the Provincial Council Member Mr. Aday argued, “it is better if the southern hashds [PMF] return to their cities in the future, but the local hashds should be integrated into military institutions and be part of a security establishment, provided for by law and under a legal framework.”

References

1 Ibrahim Khalaf led field research. Mahmoud Zaki also contributed significantly to the research and analysis.

2 Population estimates vary. In interviews for this study, the mayor and local security officials estimated that the population of Tikrit was between 200,000 and 225,000. Other reports have estimated it at approximately 150,000 pre-ISIL. “More than Three Million Iraqis Displaced by Fighting,” Al-Jazeera, June 23, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/06/million-iraqis-displaced-fighting-150623165038442.html.

3 United Nations Development Program, Recovery and Stabilization Needs Assessment Report. Al Dour District and Mkeishifah Town (Baghdad: United Nations Development Program, 2015); Human Rights Watch, Ruinous Aftermath. Militias Abuses Following Iraq’s Recapture of Tikrit (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2015), https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/09/20/ruinous-aftermath/militias-abuses-following-iraqs-recapture-tikrit.

4 There are a variety of tribes and subtribes in all three areas. In al-Alam, two tribes, D’jbour and al-Obaid, are dominant. In Dour, the Shammari tribe and a number of subtribes of the D’jbouri tribe, including the Schwoghat, Albou Haider, Albou Madalal, and Albou Jama’a subtribes, are present.

5 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath.

6 Hayder al-Khoei, “Why ´Emotional´ Battle for Tikrit Will Defeat ISIS,” CNN, March 4, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://edition.cnn.com/2015/03/04/opinion/tikrit-battle-opinion/index.htm.

7 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath.

8 al-Khoei, “´Emotional´ Battle for Tikrit”; Michael Knights, “Iraq: Are Shi’a Leaders Ready for Sectarian Healing,” Al-Jazeera, April 5, 2016, accessed June 27, 2017, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/04/iraq-Shi’a‑leaders-ready-sectarian-healing-isis-sunni-160405060514772.html; Belkis Wille, Executions in Iraq Not Real Justice for Speicher Massacre (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), www.hrw.org/news/2016/08/23/executions-iraq-not-real-justice-speicher-massacre; Sanad, Speicher Conflict Intervention (Baghdad: Sanad, 2015), http://sanad-iq.org/?project=speicher-intervention.

9 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath; al-Khoei, “´Emotional´ Battle for Tikrit.”

10 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath.

11 Ibrahim Al-Marashi, “Tikrit is the Battleground for Iraq’s Past and Future,” Al-Jazeera, March 24, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2015/03/tikrit-battleground-iraq-future-150324070351169.html.

12 Iran provided significant weaponry and direct tactical support throughout much of the initial offensives in Salah ad-Din, including the reported direct engagement of the commander of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Quds Force during the start of the March 2017 advance on Tikrit. Al-Khoei, “´Emotional´ Battle for Tikrit”; Lora Moftah, “Tikrit ISIS Battle: Top Iranian Commander on Iraq Frontlines of Crucial Offensive against Islamic State,” IB Times, March 3, 2015, http://www.ibtimes.com/tikrit-isis-battle-top-iranian-commander-iraq-frontlines-crucial-offensive-against-1834142. http://edition.cnn.com/2015/03/04/opinion/tikrit-battle-opinion/index.htm

13 Al-Khoei, “´Emotional´ Battle for Tikrit”; Sharif Nashashibi, “The Risks of Mishandling the Tikrit Offensive,” Al-Jazeera, March 11, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2015/03/risks-mishandling-tikrit-offensive-150311051311135.htm.

14 Mapping Militant Organizations, Stanford University, “Kata’ib Hezbollah,” last updated August 25, 2016, web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/361; Bill Roggio, “US Airstrikes in Amerli Supported Deadly Shi’a Group,” Long War Journal, September 2, 2014, www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2014/09/us_airstrikes_in_ame.php; U.S. Department of Treasury, “Treasury Designates Individual, Entity Posing Threat to Stability in Iraq,” Press release. July 2, 2009, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg195.aspx.

15 Saif Hameed, “Iraq Special Forces Advance in Tikrit, U.S. Coalition Joins Fight,” Reuters, March 26, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-idUSKBN0MM0R220150326.

16 “Shi’a Militias Pull Back as US Joins Battle for Tikrit,” Al-Jazeera, March 27, 2015, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2015/03/Shi’a‑militias-step-joins-battle-tikrit-150327010352355.html.

17 Ibid.

18 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath; Salah al-Din police director, Ibrahim’s interview.

19 REACH, Humanitarian Overview of Five Hard-to-Reach Areas in Iraq (Geneva: REACH, 2016), 12, reliefweb.int/report/iraq/humanitarian-overview-five-hard-reach-areas-iraq-december-2016.

20 Marwan Bishara, “Analysis: Liberators or Invaders,” Al-Jazeera, March 11, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/03/analysis-liberators-invaders-150311004415129.html.

21 Salah al-Din police director, Ibrahim’s interview.

22 Al-Marashi, “Tikrit is the Battleground”; Caleb Weiss, “Iranian-Backed Shiite Militias Still Operating in Tikrit,” ThreatMatrix, March 30, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/03/%d9%8diranian-backed-shiite-militias-still-operating-in-tikrit.php; Suadad al-Salhy, “ISIL’s Fall in Tikrit May Show the Way for Iraqi Army,” Al-Jazeera, April 1, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2015/04/isil-fall-tikrit-show-iraqi-army-150401085105863.html.

23 Nashashibi, “The Risks of Mishandling.”

24 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath.

25 Ibid.

26 HRW, Ruinous Aftermath.

27 Ibid.

28 “Special Report: After Iraqi Forces Take Tikrit, a Wave of Looting and Lynching,” Reuters, April 3, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-tikrit-special-re-idUSKBN0MU1DP20150403.

29 Karim al-Noori, a spokesman for the Shi’a PMF, confirmed that 80% of Shi’a volunteer fighters had left Tikrit. “Shi’a Fighters Leave Tikrit amid Looting Complaints,” Al-Jazeera, April 4, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/04/Shi’a‑fighters-leave-tikrit-looting-complaints-150404194947715.html.

30 “Shi’a Fighters Leave Tikrit amid Looting Complaints,” Al-Jazeera; “Special Report: After Iraqi Forces Take Tikrit, a Wave of Looting and Lynching,” Reuters, April 3, 2015, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-tikrit-special-re-idUSKBN0MU1DP20150403.

31 Less influential but present are the Khorasani Brigades and the Ali al-Akbar Brigade.

32 Nour Samaha, “Iraq’s ´Good Sunni´,” Foreign Policy, November 16, 2016, accessed June 27, 2017, foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/16/iraqs-good-sunni/.

33 Access to Tikrit, al-Alam, and Dour for international researchers was denied, and there was sensitivity surrounding the nature of this study and its questions. For that reason, it was not possible to survey as wide a sample of local officials, community leaders, and residents as in other areas. Those interviewed may reflect a particular leaning toward Sunni tribal fighters, given their affiliation.

34 Other interviewees suggested much higher estimates. One leading tribal elder and political representative, Shaikh Marwan Nagi al-Gibara, estimated that the number of forces in the different Sunni tribal PMF units in both Dour and al-Alam totaled some 2,000 fighters, with another 1,000 fighters active in the unit that operates in Tikrit.

35 Local officials estimated that approximately 80 percent of the displaced had returned to Dour and al-Alam, and an April 2017 IOM study found that 80 to 90 percent of families who were displaced from Tikrit city center had returned. The IOM found that an estimated 21,160 families had returned, of an estimated 23,500 to 26,500 who had originally been displaced from Tikrit city center. Seventy percent of those returned between June and August 2015. International Organization for Migration, Obstacles to Return in Retaken Areas of Iraq (Baghdad: International Organization for Migration (Iraq Mission), 2017), 62, http://iraqdtm.iom.int/specialreports/obstaclestoreturn06211701.pdf.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 According to HRW, individuals whose immediate relatives joined ISIL are to be expelled from Salah al-Din unless cleared of affiliation with ISIL. The decree also provides a legal basis to confiscate those families’ property. The decree was reportedly based on tribal law and so included a provision that exempts families who kill their ISIL-affiliated relatives or surrender them to the Iraqi authorities. Human Rights Watch, Iraq: Displacement, Detention of Suspected “ISIS Families” (Erbil: Human Rights Watch, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/05/iraq-displacement-detention-suspected-isis-families. Judit Neurink, “Islamic State Families Fear Persecution in Iraq,” Al-Monitor, June 7, 2017, accessed June 27, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/06/iraq-isis-families-shahama-camp-fallujah-tikrit.html#ixzz4kRg9ZYLT; HRW, Iraq: Displacement, Detention.

39 The decree also seems to be one of the reasons for corruption in the vetting process, with IDPs who were not affiliated with ISIL nonetheless blackmailed into paying bribes to avoid being branded with an ISIL affiliation. Sanad, Update on IDP’s Return Status in Beiji District – Saladin Governorate (Baghdad: Sanad, 2017).