Iraq after ISIL: Kirkuk

ISIL’s advance on Kirkuk created opportunities for Kurdish forces to tighten control over oil resources and Kirkuk city in this most coveted part of the Disputed Territories; however, a strong (for now officially accepted) PMF presence in the south, anchored with local Turkmen PMF forces, threatens future stability once ISIL is pushed out of Hawija district.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

ISIL’s advance on Kirkuk, the most coveted part of the Disputed Territories, created opportunities for Kurdish forces to seize control over oil resources and Kirkuk city. However, although Peshmerga forces held the line when Iraqi forces fled, they could not prevent continued ISIL security threats, nor retake the predominantly Sunni Arab areas taken by the group in 2014. This led to an agreement in February 2015 that allowed the entry of Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) into the governorate. Since then, both Kurdish forces and PMF forces have coordinated in the fight to hold off ISIL, both directly and through the mobilization of various, local and minority forces in Kirkuk. The strongest of these forces, drawn from Kirkuk’s Shi’a Turkmen minority, provides an anchor for the Badr Organization and facilitates a line of control that reaches from just south of Kirkuk city into the adjacent Tuz Khurmatu district (“Tuz”) of Salah ad-Din.

This research summary discusses broader LHSF trends over all in Kirkuk, but with a particular focus and a greater number of interviews in Kirkuk city and surrounding areas. At the time of writing, all forces were preparing to expel ISIL from one of its last remaining strongholds in and around Hawija district. However, the positioning of different local and sub-state security forces (LHSFs, as this study refers to them) within Kirkuk seemed to guarantee future rounds of conflict between the governorate’s different ethnic, confessional, and political stakeholders. Concerns about security and political conflicts have resulted in significant consequences for civilians – Kurdish authorities ejected Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen IDPs from the government, and Kurdish and Shi’a Turkmen forces forcibly displaced resident Sunni Arabs in areas under their control on the grounds of military necessity and in acts of retaliation for ISIL attacks. Such expulsions were often accompanied by mass property destruction and the demolition of Arab villages. With Kirkuk’s status still unresolved, such actions carry a whiff of ethnic gerrymandering.

Background: Historical Divisions and Demographic Politicking

Historically an important waystation along an important Ottoman trade route, Kirkuk has long been a melting pot of different ethnic, confessional, and political groups. Today, Kirkuk city is home to Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, and a variety of Islamic, Christian and other sects. Population estimates have tended to be heavily politicized and widely mistrusted; however, reporting by groups like the International Crisis Group tended to estimate between 500,000 and 700,000 residents in Kirkuk as of 2007, roughly half of the total population of the governorate.2

Kirkuk grew in regional importance when exploratory drilling near the eternal fires of Baba Gurgur, directly northwest of Kirkuk city, led to a spectacular gusher that flooded the area with oil in 1927. Kirkuk governorate’s oil fields contain today an estimated 12 percent of Iraq’s total reserves. Kirkuk’s oil resources have made it a significant bone of contention among different national and local stakeholders since that time, which has led to waves of significant demographic shifts as different stakeholders and groups try to benefit from its oil revenues or control them. Following the opening of the Baba Dome of the Kirkuk oil field, Arab, Assyrian, and Kurdish oil workers migrated to Kirkuk, shifting the ethnic demographics of the region. Prior to the Baath regime, Kirkuk city had a Turkmen majority and the ethnic composition of the governorate as a whole was roughly 48 percent Kurdish, 28 percent Arab, and 21 percent Turkmen.3

After the Baath Party came to power in 1968, Kirkuk was increasingly subject to “Arabization” policies, which attempted to shift the ethnic demographics in favor of Arabs. The regime in Baghdad limited Kurdish property ownership, expelled Kurdish civil servants from Kirkuk, deported Kurds suspected of membership in Kurdish insurgent parties, prevented the return of Kurdish residents who left the governorate, and resettled hundreds of thousands of Arabs from other parts of Iraq there.4 Arabization policies in the 1980s included the mass killing of Kirkuk’s Kurdish residents, and the levelling of Kurdish villages.5 This reached its peak in what became known as the “Anfal” (“the Spoils”) campaign from February until September 1988.6

Locals interviewed for this study said that during this Arabization period, the lands of (Shi’a) Turkmen groups in Turklan, Taza, Bashir and Daquq areas were also seized and subsequently leased to Arab settlers. These events have a direct bearing on Kirkuk’s security today. As an official from Taza Khurmatu, a Shia Turkmen city directly south of Kirkuk city, explained, the source of ongoing strife between Arabs and Turkmens goes back to the forced demographic and property shifts of Saddam’s rule.

Key Facts: Kirkuk

Population: 1 million

Ethnic Composition: Kurdish and Arab majority, sizeable Turkmen population

Date taken by ISIL: June 2014

Date reclaimed: August 2014-ongoing; most Sunni Arab areas (e.g., Hawija) still under ISIL control

Forces engaged: PUK-Peshmerga, Turkmen PMF, Shi’a Arab PMF (Abbas Combat Division, Imam Ali Brigades, Karrar’s Sons Brigade), local police

Overall Control: PUK-Peshmerga

LHSFs present: PMF Turkmen Brigades 16 & 52 (Badr), Abbas Combat Division

Key Issues:

- Continued ISIL presence in Hawija

- PMF and Peshmerga forces limiting Arab Sunnis resettlement and IDP presence

- PMF and Peshmerga role and area of control after the defeat of ISIL a potential clash point

Following the US invasion of Iraq and the fall of the Baath regime, Kurdish political parties finally gained a dominant influence in Kirkuk.7 Kurdish parties, with significant international advice and support, were also able to negotiate for the inclusion of Article 58 in the 2003 Iraqi Transitional Administrative Law (TAL), which functioned as an interim constitution.8 Article 58 called for measures to “remedy” the forced demographic changes that had taken place under the previous regime, specifically in Kirkuk, including the establishment of a property claims commission, some form of compensation or alternate employment for those who lost their jobs, and a “permanent resolution” to the status of Disputed Territories once these restorative measures were taken. The main provisions of Article 58 were transferred into the 2005 Iraqi Constitution through Article 140, which required all steps of Article 58 to be completed; a referendum – to be held no later than end of 2007 – would then determine the status of Kirkuk and other Disputed Territories based on the “will of their populations.”9 This referendum has never been scheduled.

Articles 58 and 140 triggered a new round of demographic shifts. The Iraqi Property Claims Commission established under Article 58, had the authority to allocate property and land to returning Kurds. Particularly after the announcement of compensation schemes and property re-allocations, thousands of Kurdish families flooded into Kirkuk district.10 Many of the Kurdish returnees’ original homes and villages were destroyed, so many squatted in Kirkuk city. The flood of Kurdish returnees, and other Kurdish parties efforts to increase local political control increased tensions with other communities, who felt their status in Kirkuk was threatened.11

These new sources of intercommunal tension, the unresolved political status, and the growing Sunni Arab insurgent violence in Iraq led to a fraught security situation in Kirkuk. Much of the worst violence took place in Kirkuk city and the district of Hawija, on the southwest border with Salah ad-Din. According to Michael Knights, “When Baghdad was at its worst in 2007, urban Kirkuk matched its per capita incident rate of one attack per month per 5,000 residents.”12 He further noted that as Baghdad’s security improved in 2010, Kirkuk’s incident rate per capita was three times higher than the capital’s.13 However, unlike other areas wracked by Sunni insurgent violence at this time, there was no major American counterinsurgency push in Kirkuk (with the exception of two smaller Sahwa groups in Kirkuk city and Hawija). Due to political sensitivities, the primary security actor in Kirkuk since 2003 has been the local police, which reports to both the Provincial Council and the Ministry of Interior in Baghdad.14 Despite this dual reporting structure and the multi-ethnic make-up of most units, the local police was effectively a Kurdish-led force.15

Although local forces and political actors were dominant, both the Baghdad-led Federal Government and the KRG maintained a security presence in Kirkuk prior to 2014. The Iraqi Army’s 12th Division was fully operational in 2008 and had 15,000 soldiers in 2013.16 The PUK-led Peshmerga (Unit 70) and Kurdish Asayish forces affiliated with the KDP and the PUK were also present, even though the presence of Kurdish Security Forces was legally questionable in areas outside the Kurdistan Region’s borders. The Kurdish Security Forces’ conduct led to resentment among non-Kurdish communities, as did their construction of a fortified barrier around Kirkuk city in 2013, which separated the city from Sunni Arab areas but left a corridor open to the north, toward the Kurdistan Region.17

As a result of this background, the demographic composition of different areas is crucial to understanding the current lines of control and conflict points in Kirkuk. The following summary (with population estimates based on 2007 data from the United Nations) illustrates the mixed demographic nature:18

- Kirkuk (ca. 570,000) – Mixed demographics by sub-districts (see below)

- Hawija (ca. 215,000) – Sunni Arab majority in all sub-districts (Hawija, Rashad, Riyadh)

- Daquq (ca. 75,000) – Shi’a Turkmen majority, with a significant share of Kaka’i Kurds and Arabs

- Dibis (ca. 40,000) – Mostly Kurdish, but a Sunni Turkmen majority in its largest settlement, Altun Kupri; Arab villages in areas close to Kirkuk and Hawija districts

Kirkuk district’s demographics are strongly divided by sub-districts (* indicates sub-districts only recognized by Kirkuk governorate and not by the Federal Government). The following population estimates are based on 2008 Government of Iraq data:19

- Kirkuk central (ca. 700,000) – Kirkuk city: 46 ethnically diverse neighborhoods

- Multaqa (west of Kirkuk)(ca. 45,000) – Mullah Abdullah town (Arab) and 30 Arab villages

- Yaychi* (west of Kirkuk)(ca. 23,000) – Yaychi town (Sunni Turkmen), 20 – 30 Arab and Kurdish villages

- Taza (south of Kirkuk) (ca. 30,000−40,000) – Taza Khurmatu town (Shi’a Turkmen), Bashir village (Shi’a Turkmen), Chardaghlu (Turkmen), and 18 Arab villages

- Laylan (southeast of Kirkuk) (ca. 90,000) – Laylan town (mixed) and 54 villages (ca. 30 Kurdish villages, 11 Arab villages, and a handful of Shi’a Turkmen and mixed Arab-Turkmen villages)

- Qara Khanjir* (east of Kirkuk)(ca. 35,000−42,000) – Qara Khanjir town (Kurdish) and 45 Kurdish villages

- Schwan* (north of Kirkuk)(ca. 37,000) – Schwan town (Kurdish) and 16 Kurdish villages

ISIL Capture and Immediate Aftermath

In early June 2014, ISIL moved rapidly across Ninewa and Salah ad-Din and began its assault on Kirkuk. ISF forces retreated from their posts in Kirkuk, leaving large swathes of territory undefended. While the assault on Mosul was still ongoing, ISIL captured the Arab-majority areas of Kirkuk governorate (in Hawija, Daquq, and rural Kirkuk districts), prompting mass displacement; many civilians fled to Kirkuk city, Taza Khurmatu city, and other safe havens. Many Arab villagers close to the emerging frontlines around Kirkuk city moved in the opposite direction, toward ISIL-held Hawija town, which at the time was easier to access than Kirkuk city. According to IOM, about 115,000 people were displaced immediately after ISIL’s advance.20

As ISIL advanced on Kirkuk city, Kurdish Security Forces deployed in the city and surrounding areas. Having lost Mosul and Tikrit, ISF forces were broken, demoralized, and consumed with fighting off threats in Samarra, on the road to Baghdad. The Kurdish Security Forces took exclusive control of Kirkuk city and its immediate environs, including the Kirkuk oil field, and the K‑1 military base, where the Iraqi Army’s 12th Division had abandoned significant amounts of military equipment. While PUK forces seized control of the area around Kirkuk city, KDP-led forces secured most of Kirkuk’s oil assets, including the Avaneh dome of the Kirkuk oil field, and the Bai Hassan field in Dibis district.21 PUK-affiliated forces held on to the Baba dome of the Kirkuk field, and the Khabbaz field.22

Undermanned and ill-equipped, the Kurdish Security Forces struggled to fend off ISIL around Kirkuk. On June 17, 2014, ISIL captured Multaqa sub-district, west of Kirkuk city.23 The same day, the group also took control of Taza sub-district, south of Kirkuk city, with the exception of its capital, Taza Khurmatu. According to locals, ISIL killed 52 Shi’a Turkmens in nearby Bashir village on June 17, 2014, in a pattern of ethnically motivated killing similar to the massacres the group staged in three Shi’a Turkmen villages in nearby Tuz.24 However, with the support of US-led Coalition air strikes and an inflow of volunteers from other Kurdish areas, Kurdish forces managed to hold the line there and halt ISIL’s advance.25

Meanwhile, by end of June, the Badr Organization deployed (unclear on whose orders, potentially their own) to rural Kirkuk and, together with a large component of locally recruited Shi’a Turkmen fighters, mounted a counter-offensive to retake Bashir.26 Although the operation failed at that time, it marked the entry of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) into Kirkuk’s security dynamics, and the initial mobilization of Kirkuk’s Shi’a Turkmen community and, to a lesser extent, Sunni Arab and Kakai Kurdish communities.27 By early 2015, a series of ISIL attacks and unsuccessful Peshmerga efforts to stop them had led to a situation in which local Kirkuk officials, including the governor, viewed PMF support as necessary and even tacitly welcome.28 This scenario led to a controversial February 2015 agreement between the local governorate authority and the PMF, in which the latter agreed to assist in retaking outlying areas like Hawija, while Kurdish forces would retain control of and defend the city of Kirkuk (temporarily).29

Since then, Kurdish forces and PMF, including a range of locally mobilized, minority forces, have jointly taken responsibility for security and anti-ISIL operations in Kirkuk, including some joint operations. This is perhaps best illustrated by an operation that took place on April 30, 2016, to recapture the Shi’a Turkmen-majority village of Bashir and surrounding Arab villages, which lie about ten kilometers south of Taza Khurmatu. ISIL captured this area in early June 2014. In March 2016, the group’s fighters launched 42 Katyusha rockets armed with a mixture of mustard gas and chlorine from their position in Bashir onto Taza Khurmatu city, which is the site of a PMF base and an important transit point for Coalition forces. The attack wounded over 800 civilians and prompted a mass evacuation. Shortly afterwards, Coalition air strikes struck ISIL positions in Bashir.30 On April 30, 2016, an operation to recapture Bashir and nearby Arab villages was launched.

A large coalition of forces participated and were coordinated under a joint command that was set up for this single operation. Peshmerga forces advanced on the right flank with support from Coalition air strikes. The Abbas Combat Division led the left flank; its approximately 1,000 Shi’a Arab fighters arrived from Kerbala on February 4, 2016, with the sole purpose of participating in this operation. They were supported by Iraqi air strikes and by the eight local Turkmen PMF regiments, 100 Shi’a Arab fighters from Karrar’s Sons regiment,31 50 Shi’a Arab fighters from the Imam Ali Brigade, 50 Shi’a Turkmen fighters from the PMF’s 52nd Brigade in Amerli (Tuz district), and the local police force in Taza and Bashir. (Following Bashir’s recapture, in May 2016, ISIL fired chemical weapons onto the PMF forces stationed in the area.32)

Since ISIL’s initial onslaught in 2014, Kurdish forces have managed to push the group back and shift the entire frontline, which ran from the northwestern to the southeastern corner of the governorate, a few dozen kilometers to the south, although ISIL has made occasional inroads on this line. In 2016, Kurdish forces erected an almost contiguous, fortified security barrier along the frontline, akin to the one built around Kirkuk city, which divides Sunni Arab areas from multi-ethnic and Kurdish-majority areas throughout the governorate.33 Nonetheless, there have been continuing ISIL attacks in areas in and around Kirkuk city. In one such attack on October 21, 2016, as Coalition efforts to retake Mosul were underway, ISIL launched a diversionary attack on Kirkuk city by activating sleeper cells and orchestrating infiltration from the outside. The group attacked multiple targets, including the governorate building, police stations, and the headquarters of the Kurdistan Democratic Party. The Peshmerga, the Asayish, and the local police, which were reinforced by the Anti-Terrorism Directorate of Sulaimani and local volunteers, could only reestablish control of the city after 48 hours and suffered heavy casualties in the fights (this attack unleashed retaliatory attacks by Kurdish Security Forces on Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen populations; see section below).34

Divided Control

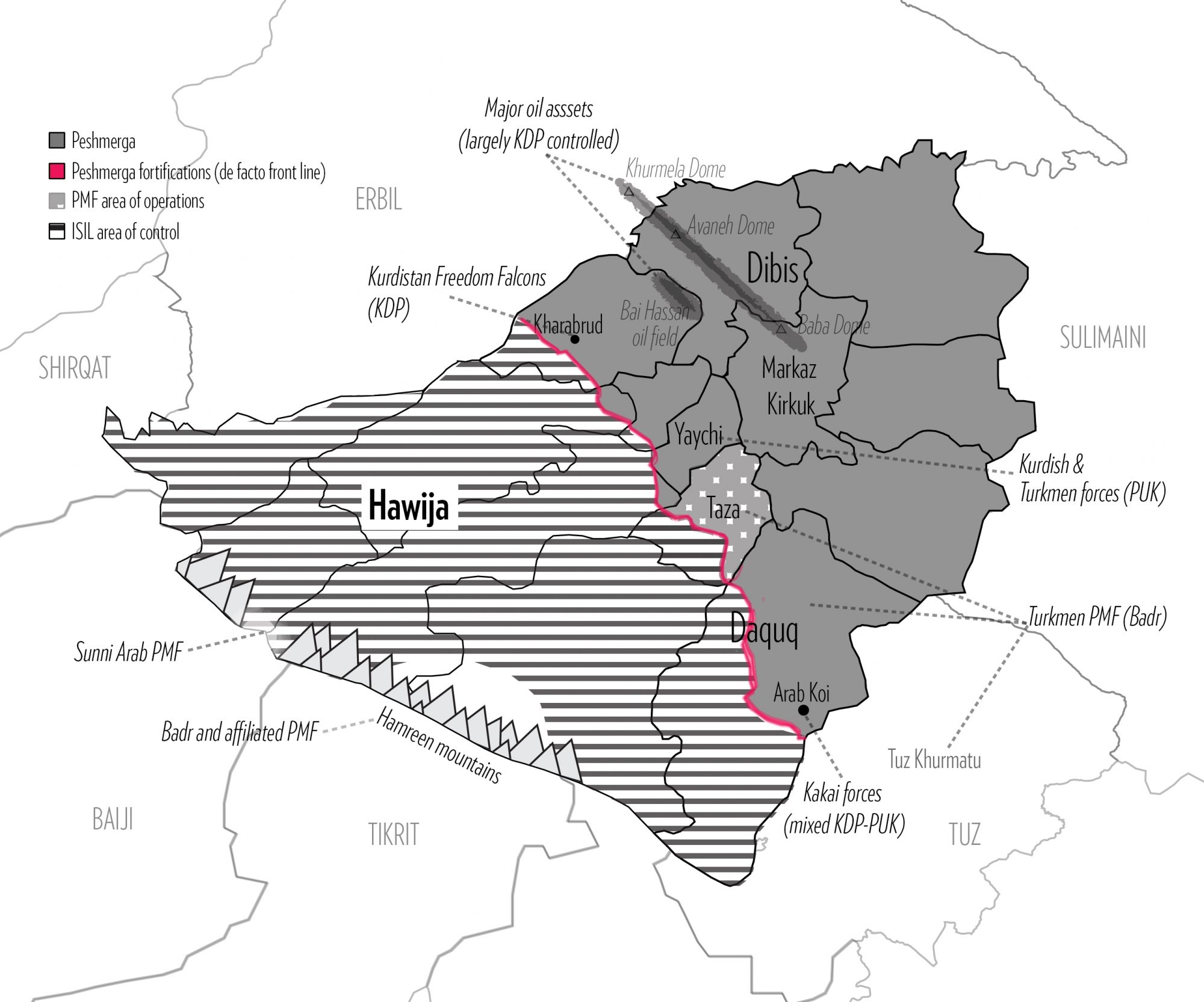

The response to the ISIL threat dramatically changed the security dynamics in Kirkuk and created new patterns of control, which continued to prevail at the time of writing. According to a Middle East Research Institute mapping of pre- and post-ISIL areas of control in Kirkuk, Peshmerga forces were not the primary security actor in Kirkuk prior to 2014 – they held a predominant influence in only small parts of Dibis and Kirkuk districts.35 However, following the ISIL invasion in 2014, their area of control increased to include a significant portion of Dibis district, parts of Daquq district, and more of Kirkuk district, including the governorate’s capital, Kirkuk city. The February 2015 agreement mapping out lines of control between Kurdish forces and the PMF largely still stands: the PMF (mostly Badr) secure areas in Taza sub-district and conduct clearing operations in Daquq district via their Turkmen proxies, while Sunni Arab and Shi’a Arab forces of the PMF are building up their presence in the Hamreen mountains in preparation to retake Hawija. KRG Security Forces have retained exclusive control in all other parts of the governorate, including Kirkuk city. ISF are not present in Kirkuk – with the notable exception of the local police.

At the time of writing, ISIL forces continued to control or have operating space over the vast majority of the southern half of Kirkuk, essentially any area south of the Kurdish security barrier, and north of the Hamreen mountains. Efforts to retake Hawija were on hold as ISF forces finished operations in Mosul; now, they focus on retaking Tal Afar before moving on to Hawija. The composition of forces who will participate in the Hawija offensive remained unclear at the time of writing.36

The below sections will discuss the patterns of control and dynamics within Kurdish and PMF areas of control separately.

Kurdish Sphere of Control

While Kurdish forces control most of the governorate outside ISIL’s reach, in many places they do so in alliance with, or via, local forces. For example, in Yaychi sub-district, just outside Kirkuk city, a small, mixed Kurdish-Turkmen tribal force supports PUK forces to control the area.37 (There were rumors also about a sizeable Turkmen force backed by Turkey in Yaychi, although their presence could not be confirmed, and local officials denied they existed.38) In Daquq district, the Kakai minority – a Kurdish-speaking, non-Muslim minority of about 75,000 individuals in Iraq – formed three regiments of 650 forces under the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs in 2015.39 In Dibis district, the PUK-Peshmerga forces have reportedly held the frontline south of Kharabrud in alliance with Iranian Kurdish fighters who have ties to the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK).40

There is also a split in control of certain areas between the PUK and KDP wings of the Kurdish forces. Generally, PUK forces control Kirkuk city and most of the surrounding areas, while KDP forces maintain control of the most significant oil resources, with the exception of the Baba dome of the Kirkuk oil field.41 However, there are overlapping areas of control and mutually contested areas. Although the PUK-Peshmerga have the upper hand in Kirkuk city, both KDP- and PUK-affiliated Asayish forces and Kirkuk’s local police also retain a prominent role in security. In Daquq, both PUK- and KDP-affiliated forces vie for the allegiance of the local Kakai fighters.

Tensions between the PUK and KDP over the control of oil resources have deepened the divide among Kurdish leaders in Kirkuk. In August 2016, the KRG entered an agreement with Baghdad to export oil from the fields operated by Baghdad’s North Oil Company (secured by PUK) to Turkey through the KDP-controlled pipes, and to split the proceeds in half.42 Although the agreement included provisions for petrodollar payments to Kirkuk in the range of $10 million per month, some within the PUK leadership rejected the deal as it seemed to cement KDP interests in Kirkuk.43 Disagreement over a tender to build a refinery has led to open confrontation. In March 2017, PUK-affiliated Black Force special police units seized control of a pumping facility near Kirkuk, which collects oil from North Oil Company-operated facilities, to pressure Baghdad to increase the share of crude refined in Kirkuk, and to pick the “right” bidder.44

PMF Areas of Operation

The Popular Mobilization Forces have a great deal of autonomy in the areas south of Kirkuk city, although the Peshmerga are also present. There is a strong demographic pattern to the areas where PMF have deployed and played a more active role, in that PMF have predominantly tried to assert areas in heavily Shi’a Turkmen areas of the governorate.45

The February 2015 power-sharing agreement allowed the PMF to establish a military base in Taza Khurmatu, a dozen kilometers due south of Kirkuk city, and Badr forces are also known to be based out of the Hamreen mountains on the southern border of the governorate. Within weeks of the agreement, the Associated Press reported that 2,000 fighters had arrived at the Taza base, and militia leaders estimated that a total of 5,000 fighters, some of whom had arrived from outside Kirkuk, were present in the governorate in February 2015.46 In June 2017, one security representative interviewed for this study estimated the total number of PMF forces present in Kirkuk governorate at 7,000, a large share of whom are locally mobilized Shi’a Turkmen.

The Turkmen forces began to be established in March 2015 and were trained (including by Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah instructors) at the Taza base.47 Most Shi’a Turkmen forces belong to the PMF’s “northern front” operations, which have clear ties to Badr.48 These forces are organized into two groups: Brigades 16 and 52. These brigades operate all the way from Taza Khurmatu to the southernmost village in Tuz district (in Salah ad-Din); Brigade 16 is most active in Kirkuk’s Taza sub-district, and Brigade 52 is engaged in the rural areas connecting Taza Khurmatu to Tuz Khurmatu.49 Although the exact force numbers fluctuate and are difficult to estimate, Brigade 16 alone has six regiments, and each of these comprises 150 – 300 Shi’a Turkmen forces.50 Two further Turkmen PMF regiments operate in Taza sub-district, in coordination with the “northern front” operations but independent from Badr.51

The mobilization of these local Turkmen PMF forces may be significant for future local dynamics because while each unit or brigade tends to affiliate with a larger Shi’a PMF, on a day-to-day basis, they act as semi-autonomous forces that can hold areas on their own. To better understand these dynamics, researchers for this study explored the different groups that operate in and control recently recaptured areas in Taza sub-district: the Turkmen Bashir village, which has been a flashpoint between ISIL and PMF forces, and eight nearby Arab villages (Aziziyya, Big Humayra, Small Humayra, Isteeh, Jadida, Mur’iyya, Shamsiyya, and Tali’a).52

As regards the conduct of Turkmen PMF conduct in their areas of operation, a local official in Taza Khurmatu claimed they were not well disciplined and often acted outside the remit of the law. As an example, he stated that PMF fighters intimidated and disrespected locals at security checkpoints. Making things worse, the local police is often unable to enforce the law against PMF fighters because of their powerful connections (wasta). When confronted by these allegations, an interviewed commander claimed the Turkmen PMF have very good relationships with locals because they are also part of the community. He admitted to some acts of criminality against civilians due to a “lack of discipline” among Turkmen forces, but argued these problems were not systemic and often originated in business or family conflicts.

In addition to the Turkmen forces, the PMF in Kirkuk also include two Sunni Arab forces who report to the formal PMF structure (primarily Badr)53 and whose sole aim is to liberate Hawija. These forces are based in the Hamreen mountain range, which separates Baiji and Tikrit districts in Salah ad-Din from Hawija in southern Kirkuk.54 The Hawija’s Liberation hashd is led by Wasfi al-Assi, chieftain of the Ubaid tribe. The PMF trained and equipped the group’s first two regiments of 600 – 700 fighters in 2015.

They have been fighting in the local area but have also been deployed in support of PMF operations in nearby areas, including areas in Salah ad-Din. A new round of recruitment opened in September 2016 to expand the force to up to eight regiments (approximately 2,500 fighters).55 The second group is under the supervision of the Nu’aym tribe’s chief, Sufyan Omar al-Ali an-Nu’aymi, who announced in July 2016 the establishment of the Southwest Kirkuk hashd. According to news reports, this Sunni Arab force includes 1,000 fighters,56 but this research could not confirm their deployment.57

Although the power-sharing agreement permitted PMF operations in areas south of Kirkuk, it is not a division of labor that excludes Peshmerga activities and influence in areas carved out for PMF operations; for example, the campaign to retake Bashir involved significant Peshmerga forces (see above). An interesting example of Kurdish presence is the Free Iraq Division, a 1,500-strong group of largely Sunni fighters of mixed ethnicity (about 50% are Kurds, 30% are Arabs, and 20% are Sunni Turkmen) who are active in the PMF area of operations near Bashir.58 Although this unit was launched in 2014 as part of the popular mobilization against ISIL,59 its status remains ambiguous. It has not been formally incorporated within the PMF and its fighters receive neither salaries nor official recognition. The group has strong ties to the KRG leadership, and many view it as an attempt to balance the Shi’a PMF presence in Kirkuk governorate.60

Blocked Return, Forced Displacement, and Ethnic Gerrymandering

The ISIL invasion of 2014 presented the KRG with the prospect of achieving their long-held political goal of making Kirkuk an official Kurdish territory. “I saw it in an opportunistic way,”61 said KRG President Masoud Barzani when asked about the Iraqi Army’s inability to secure Kirkuk. The side-effects of this geopolitical expansion were felt particularly harshly by the governorate’s Arab population, who were subject to multiple rights violations. PUK-Peshmerga and Asayish security forces have forcibly displaced Arab IDPs and resident population, conducted unlawful arrests, razed villages, and blocked returns. The Turkmen PMF have also harassed, abused, and destroyed the property of Arab residents in their areas of operations, but their area of operations, and so the impact of such abuses, has been more limited.

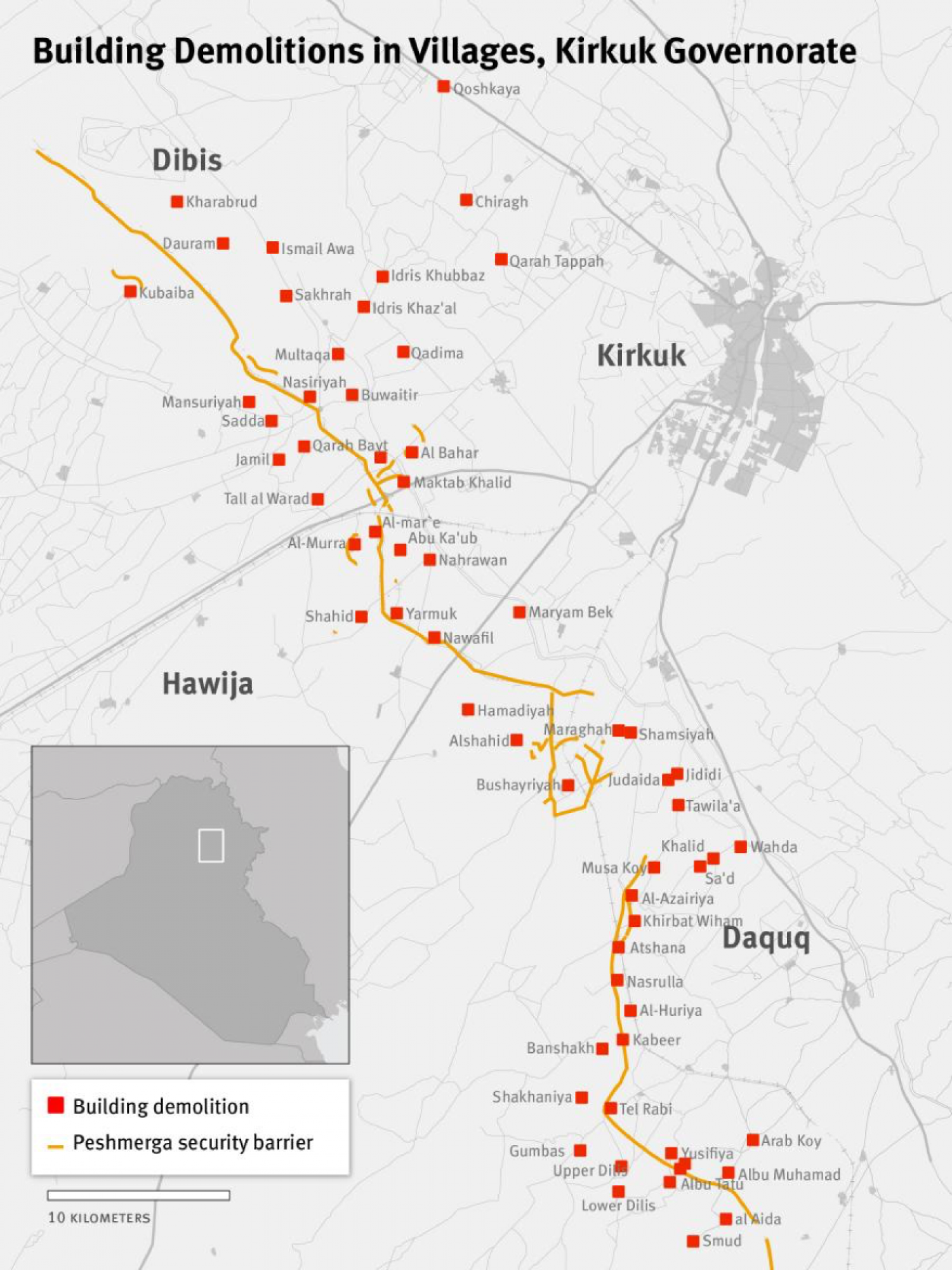

Human Rights Watch documented the widespread destruction of homes in 60 Sunni Arab villages between August 2014 and May 2016 along the shifting frontline with ISIL (on both sides of the security barrier)(see HRW’s map below).62 These acts were committed to punish alleged cooperation with ISIL or to reverse the demographic changes of the Baathist “Arabization.” Several villages lie further from the frontlines but close to key oil infrastructure.63 Based on satellite imagery, site visits, and interviews with locals, Human Rights Watch alleged that the Kurdish Security Forces were responsible for the partial and often complete destruction of these villages, a few of which had never been captured by ISIL.64 The KRG denied most of these allegations, claiming that the damage resulted from fighting or demining.65 Return to these villages has been restricted, and many residents live in IDP camps today.66 KRG President Masoud Barzani told Human Rights Watch in July 2016 that the KRG would not allow Sunni Arabs to return to villages that had been “Arabized” by former President Saddam Hussein.67

KRG forces and officials have tended to argue that these attacks were motivated by security threats. Many of the attacks on Kirkuk’s Arab communities and limitations on their rights have appeared to also be motivated by revenge for attacks on the Peshmerga. Throughout 2016, there have been a series of attacks on Peshmerga forces in Kirkuk city and other areas, presumably instigated by ISIL sleeper cells among the Sunni Arab population in the city. For example, the October 21, 2016 attack in Kirkuk city triggered widespread retaliation by the Kurdish Security Forces against Arabs throughout the governorate.68 Political officials blamed Arab IDPs in Kirkuk for instigating the attack, and in response, at least 250 IDPs from outside Kirkuk were expelled,69 more than 100 homes in informal settlements in Kirkuk city were razed, and the populations of two Arab villages (comprising at least 150 families) in Dibis were forcibly displaced.70 Local media also reported that the Kurdish Security Forces completely emptied Qarah Tabah village in Yaychi sub-district, thought to be a source of ISIL infiltration for the assault on Kirkuk.71 At the time of research, reports still had not confirmed the return of IDPs to the two villages in Dibis, but some residents were permitted to return to Qarah Tabah in March 2017, according to local news reports.72

The expulsion of IDPs from other governorates following the October 2016 incident fit within a larger pattern of discrimination against and expulsion of Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen IDPs from outside Kirkuk. A total of 12,000 people were expelled in September 2016 alone.73 Sunni Turkmen IDPs who were expelled told Human Rights Watch that the orders were implemented due to a perception that Sunnis had ties to ISIL.74 The IDPs who were forcibly expelled were primarily from areas where ISIL had already been forced out. However, many of those areas were controlled by PMFs that were hostile to returning populations (e.g., in Tuz).75 This situation continued as of the time of writing.

Shi’a Turkmen PMF have also engaged in similar patterns of abuse against Sunni Arabs, although to a lesser degree. This phenomenon is best illustrated by return patterns in and around Bashir, which is currently under Shi’a Turkmen PMF control. Bashir itself has traditionally been a Shi’a Turkmen village but surrounded by predominantly Sunni Arab villages. Overall return is relatively low in Bashir and the surrounding villages due to security reasons; the area is within the reach of ISIL artillery, and the group has already attempted to recapture Bashir. In addition, property damage in Bashir and surrounding villages is significant, with many homes damaged by ISIL artillery or booby-traps. According to a local official, 875 of the 1,875 houses were completely destroyed in Bashir.76 Roughly the same amount of property destruction has happened in surrounding Arab villages, according to locals. However, return has not been the same. Of the estimated 600 families (3,880 persons) displaced from Bashir, 150 Shi’a Turkmen families have already returned. However, not a single displaced Arab has returned to the neighboring villages, despite a directive from the sub-district manager (the local authority) in Taza that they were free to do so. A mukhtar from one of the Arab villages added that locals were very afraid of the Turkmen PMFs due to news reports on these forces’ conduct, including, for example, assassinations of Arabs in Tuz district.

A local official explained that the Shi’a Turkmen PMF block the return of Arab IDPs to the liberated areas around Bashir at security checkpoints, which they man together with the Peshmerga and the local police. An interviewed PMF commander stated that the return of Arab IDPs was a sensitive issue and stressed the need for detailed security checks to weed out innocent Arab returnees from those who were affiliated with ISIL or supported it (the PMF is part of the joint security committees that vet returning IDPs). He also added that tribal reconciliation efforts must precede returns to address grievances and prevent a spiral of violence due to resentments on both sides.

The destruction of homes and evictions of the Arab population in Kirkuk governorate have been justified on the grounds of military necessity or described as retaliations for attacks on Kurdish or Shi’a Turkmen forces. However, such restrictions on the rights of Arabs effectively reverse the effects of the Baath’s “Arabization” policies and might be understood as a tit-for-tat in the forced demographic changes that have characterized Kirkuk over the last three decades. In Kirkuk, the forced displacements of, and restrictions on, Sunni Arab populations by all sides carry a distinct flavor of ethnic gerrymandering (although this is not the argument made by most KRG officials).

Future Control

At the time of writing, all eyes were on ISIL’s remaining stronghold in Hawija. However, most locals assume that Hawija will not be the end of conflict in Kirkuk, but the beginning of another cycle of it. Assuming that the Hawija operations are led by ISF (as is anticipated to be the case), the re-entry of Iraqi forces into Kirkuk will likely test Kurdish control. Many also expect that political clashes over whether PMF are allowed to participate in the Hawija operations will upset the so far cooperative relationship between PMF and Kurdish forces. All 40 key informants interviewed for this study expected a deterioration of inter-community relations after ISIL’s ouster from Hawija and potential clashes between the Peshmerga and the PMF over Kirkuk city.77 The Turkmen PMF allied with Shi’a PMF forces are growing in strength and ambition and may be used to present a threat to Kurdish control of Kirkuk city. Similar dynamics have already unfolded in Tuz district, just next door to Kirkuk. In late 2015, clashes erupted in Tuz Khurmatu city between Kurdish Security Forces and local Turkmen brigades of the PMF after the latter moved in to control parts of the city, which had been under Kurdish control since they held the defensive line against ISIL there in 2014.78 Qais al-Khazali, the leader of the League of the Righteous, a feared Shi’a militia, has already threatened to invade Kirkuk,79 and PMF forces have increasingly invested in building the capacities of the Turkmen PMF in Kirkuk. Their overall force numbers, strength, and positioning just south of Kirkuk city suggest a strong potential for Kurdish-Turkmen clashes in the regional capital. Such a move would spark serious conflict.

In addition to a potential post-Hawija stand-off, there has been a general weakening of the rule of law and security control in the last two years. The presence of competing Kurdish, Shi’a Turkmen, and other forces in the last two years has increased overall criminality and instability in Kirkuk and deepened existing fractures in local security politics. A local monitoring organization interviewed for this study said that they had recorded a steady increase in Kirkuk-based security incidents since 2016. Several community stakeholders interviewed expressed fear about criminal gangs and said they felt less safe in Kirkuk.

Most of those interviewed, from a cross-section of Kirkuk’s demographics, feared that the failure to keep these groups in check would increase future conflict risks, and so most favored demobilization. Twenty of the 40 consulted key informants, of diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds favored the local police as the only security actor in Kirkuk. Even a Shi’a Turkmen militia commander and a Sunni Arab leader close to the Arab hashd suggested these forces demobilize after ISIL’s ouster from Hawija. However, at the time of writing there were no signs that demobilization would happen soon. These different LHSF factions could very well play into any future rounds of political conflict.

Once the ISIL threat is (mostly) extinguished, locals feared that the real conflict over the long-standing political control issues in Kirkuk would break out, with regional, national and local stakeholders all involved.80 In June 2017, the KRG president called for a referendum on Kurdish independence, which was later set for September 25, 2017. The referendum would also include other Disputed Territories controlled by Kurdish forces. The effect of this unilateral referendum process is not clear. Many analysts treated it as an act of political showmanship or an attempt to increase Kurdish influence and bargaining power before the Iraqi elections.81 Regardless of the intent, the most likely immediate effect of the referendum is that it is likely to escalate simmering political conflicts, between all the different sides engaged in Kirkuk. In addition to triggering a Baghdad-KRG standoff, or exacerbating the potential conflict between Kurdish forces and the PMF in Kirkuk, the referendum has the potential to worsen competition and political conflict between the KDP and PUK. The KDP’s seizure of oil assets in Kirkuk and its grip on related revenues have created a lingering complaint among the PUK and triggered infighting among different PUK factions. Although for the moment this issue has subsided, it is not over. Many expect political tensions to increase as the September referendum approaches; it is not yet clear whether the PUK will fully support Barzani’s referendum initiative and what the local consequences will be if they do not.82 Many of the different local forces that have been mobilized since 2014, both Kurdish and of other ethnic minorities, are currently aligned with either KDP or PUK forces and could play a role in a local militarization of that ongoing competition.

Notes

1 Erica Gaston acted as editor for this piece and contributed analysis to this report. Hana Nasser provided research support.

2 Based on its interviews and research, in 2006 the International Crisis Group estimated that Kirkuk city had a population of 800,000 out of 1.5 million in the governorate. International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds: The Brewing Battle over Kirkuk (Amman/Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2006), https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/56-iraq-and-the-kurds-the-brewing-battle-over-kirkuk.pdf. A report by the NGO NCCI, based on the official 2007 Iraqi government data, estimated Kirkuk city’s population was 572,080, and that the total population was 902,019. NGO Coordination Committee for Iraq, “Kirkuk: NCCI Governorate Profile,” Date unknown, 1, www.ncciraq.org/images/infobygov/NCCI_Kirkuk_Governorate_Profile.pdf.

3 Figures from the 1957 census. Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield, Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 43. International Crisis Group noted that “In 1957, before Arabisation, census figures – considered reliable – suggested that Kurds were a plurality in the governorate, though not in Kirkuk town, where Turkomans predominated.” International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds, 2.

4 Mirella Galletti, “Kirkuk: The Pivot of Balance in Iraq Past and Present,” Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 19, no.2 (2005): 22 – 52, http://www.jaas.org/edocs/v19n2/Galetti.pdf.

5 George Black, Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993), https://www.hrw.org/reports/1993/iraqanfal.

6 According to Human Rights Watch investigations in Kirkuk and other governorates with significant Kurdish populations, the Anfal campaign, and pre-cursor attacks in 1987, resulted in: “mass summary executions and mass disappearance of many tens of thousands of non-combatants, including … sometimes the entire population of villages;” “the widespread use of chemical weapons, including mustard gas and the nerve agent GB, or Sarin, against the town of Halabja as well as dozens of Kurdish villages, killing many thousands of people, mainly women and children;” “the wholesale destruction of some 2,000 villages, which are described in government documents as having been ‘burned,’ ‘destroyed,’ ‘demolished’ and ‘purified’;” “arbitrary jailing and warehousing for months, in conditions of extreme deprivation, of tens of thousands of women, children and elderly people, without judicial order or any cause other than their presumed sympathies for the Kurdish opposition. Many hundreds of them were allowed to die of malnutrition and disease;” “forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of villagers upon the demolition of their homes.” George Black, Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds.

7 Sean Kane notes that “with the exception of nine days — March 19 to 28 — during the 1991 uprising, Kirkuk has never been Kurdish administered in modern Iraqi history.” He noted that this remained “nominally true after 2003,” – PUK peshmerga and police units helped take control of the city, they were then asked to withdraw and the U.S. military took control. However, “the Arab boycott of the political process from 2003 to 2007 and the close military relationship between the U.S. and Kurdish security services[…] allowed the Kurdish political parties to establish control over many public institutions in the province, including capturing twenty-six of the forty-one seats on the provincial council during the January 2005 provincial elections.” Sean Kane, Iraq’s Disputed Territories, United States Institute of Peace, April 4, 2011, 23, https://www.usip.org/publications/2011/04/iraqs-disputed-territories. See also International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds, 8 – 12.

8 Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution provides, “First: The executive authority shall undertake the necessary steps to complete the implementation of the requirements of all subparagraphs of Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law. Second: The responsibility placed upon the executive branch of the Iraqi Transitional Government stipulated in Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law shall extend and continue to the executive authority elected in accordance with this Constitution, provided that it accomplishes completely (normalization and census and concludes with a referendum in Kirkuk and other disputed territories to determine the will of their citizens), by a date not to exceed the 31st of December 2007.” Iraq Const. Art. 140. International Crisis Group notes the influence of Kurdish leaders in promoting this provision: “Their two leaders, Masoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani, used their positions on the 25-member interim governing Council (July 2003 to June 2004) to influence the drafting of the interim constitution, the Transitional Administrative Law (TAL), in early 2004, including Article 58, which prescribed a reversal of Arabisation […].” International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds, 7.

9 2005 Iraqi Constitution.

10 Sean Kane, Iraq’s Disputed Territories, 23. International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds.

11 Ibid.

12 Michael Knights and Ahmed Ali, Kirkuk in Transition. Confidence Building in Northern Iraq (Washington, DC: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2010), 28, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus102.pdf.

13 Ibid.

14 Shalaw Mohammed, “Kirkuk Governor: ‘Life in the City May Never Be Normal’,” NIQASH, May 16, 2013, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/security/3221; Knights and Ali, Kirkuk in Transition. The Kirkuk police also established two SWAT-like paramilitary units (emergency support units) to undertake counter-insurgency tasks that the Federal Police would normally assume in other governorates.

15 International Crisis Group, Iraq and the Kurds: Confronting Withdrawal Fears (Erbil/Baghdad/Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2011), https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/103-iraq-and-the-kurds-confronting-withdrawal-fears.pdf.

16 Mohammed, “Kirkuk Governor”; Shalaw Mohammed, “New Command Centre in Kirkuk Threatens Peace,” NIQASH, October 4, 2012, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/security/3135.

17 The Kirkuk governor ordered digging these ditches in 2013 to prevent the entry of vehicle-bound IEDs and protect its residents. However, Arabs and Turkmens viewed this plan with suspicion and accused the governor of conspiring to join the city to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The semi-circular, 2‑meter-wide, and 3‑meter-deep trench runs for 52 kilometers and embraces the city from the south while leaving its northern part open toward the Kurdistan Region. The trench features several watchtowers, and its construction cost about 3 million. Shalaw Mohammed, “Kirkuk Builds a Moat: Taking a Medieval Tack against Terrorists,” NIQASH, July 25, 2013, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/security/3257. A year later, KDP-led authorities began digging another trench separating Erbil from Kirkuk governorate, which sparked opposition from all parties in Kirkuk. Shalaw Mohammed, “Ethnic Barriers Security Trench between Erbil and Kirkuk Inflames Tensions,” NIQASH, May 8, 2014, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/security/3438/security-trench-between-erbil-and-kirkuk-inflames-tensions.htm.

18 Population estimates by the World Food Programme (2007). IAU and OCHA, Kirkuk Governorate Profile (New York and Geneva: Inter-Agency Information and Analysis Unit and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2009), http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/8E402B7CD21D076AC12576120034C81A-Full_Report.pdf.

19 Population estimates based on 2008 National ID records.

20 International Organization for Migration, Integrated Location Assessment: Thematic Overview and Governorates Profiles (Baghdad: International Organization for Migration (Iraq Mission), 2017), 33.

21 KDP expansion into Kirkuk’s oil infrastructure was significant. On July 11, KDP-affiliated forces expelled the North Oil Company, a Baghdad-affiliated company, from the Avana dome (of the Kirkuk oil field) and the Bai Hassan oil field, and the KRG contracted the KAR Group, a private company close to the KDP, to operate the facilities. (The KRG has controlled the Khurmala dome of the Kirkuk oil field since 2008). “Iraq: Kurdish Options Limited in Northern Oil Fields,” Stratfor, July 11, 2014, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/iraq-kurdish-options-limited-northern-oil-fields. Since early 2014, Kirkuk’s oil has flown through a pipeline controlled by the KRG, because Sunni insurgents had destroyed the main Iraq-Turkey pipeline and has threatened any engineers sent to fix it. David Sheppard, “With New Grip on Oil Fields, Iraq Kurds Unveil Plan to Ramp up Exports,” Reuters, June 25, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-security-kurds-oil-idUSKBN0F02KL20140625.

22 Kamaran al-Najar, Mohammed Hussein, Staff of Iraq Oil Report “Kirkuk oil crisis subsides as PUK faction withdraws,” Iraq Oil Report, March 10, 2017, http://www.iraqoilreport.com/news/kirkuk-oil-crisis-subsides-puk-faction-withdraws-21551.

23 “Daesh Controls the Building of the Forum and the Police Station West of Kirkuk,” Al Mada Press, June 16, 2014.

24 Abigail Hauslohner, “Shiite Villagers Describe ‘Massacre’ in Northern Iraq,” Washington Post, June 23, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/shiite-villagers-describe-massacre-in-northern-iraq/2014/06/23/278b0fb2-76c8-4796 – 83f7-840c277e93d8_story.html?utm_term=.6f65d8a53200.

25 Neil Shea, “Kurds Fight to Preserve ‘the Other Iraq’,” National Geographic, March 2016, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/03/kurds-northern-iraq-kurdistan-peshmerga-isis/.

26 A Daily Sabah news article at the time cites Kirkuk Governor Najmaldin Karim as welcoming the PMF, but KRG President Masoud Barzani noted that they would not be allowed in Kirkuk city. “Shiite Badr Brigades Clashes with ISIS in Kirkuk,” Daily Sabah, June 29, 2014, https://www.dailysabah.com/mideast/2014/06/29/shiite-badr-brigades-clashes-with-isis-in-kirkuk.

27 Shea, “Kurds Fight to Preserve.”

28 Ibid.; Vivian Salama, “Iraq Shiite Militias Rush to Defend Kirkuk from ISIL,” The National, February 17, 2016, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/iraq-shiite-militias-rush-to-defend-kirkuk-from-isil.

29 Abdul Aziz al-Taei, “Power-Sharing Agreement between Shia Militias and Kurds in Kirkuk,” Al Araby, February 22, 2015, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2015/2/22/power-sharing-agreement-between-shia-militias-and-kurds-in-kirkuk; “Amiri from Kirkuk: the Next Press Conference Will Be in Hawija and Charges against the Hashd Are Invalid,” Al Sumaria, February 8, 2015.

30 Campbell MacDiarmid, “Inside Taza, the Iraqi Town Gassed by the Islamic State,” Vice News, March 16, 2016, https://news.vice.com/article/inside-taza-the-iraqi-town-gassed-by-isis-with-chemical-rockets.

31 This force was established in June 2015, mostly from (university) students in Iraq’s Babel governorate. “Establishment of Sons of Karrar Regiment from Babel’s Residents and Students to Face ISIL,” Al Sumaria, June 14, 2015.

32 “Video: ISIL targeting the Hashd with Toxic Gases,” Al Alam, May 3, 2016, http://www.alalam.ir/news/1814466.

33 Al Jazeera Arabic, “Is the Kurdish Trench Paving the Way for the Division of Iraq?” YouTube video, 3:22, July 28, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a02PzXkfCz4; “‘Trench of Kurdistan’ between the Motives of the Policy and Security Requirements,” Al Jazeera, June 3, 2016.

34 Tim Arango, “ISIS Fighters in Iraq Attack Kirkuk, Diverting Attention from Mosul,” New York Times¸ October 21, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/22/world/middleeast/iraq-kirkuk.html.

35 For a projection of different security scenarios, see Humanitarian Foresight Think Tank, Iraq 2018 Scenarios. Planning After Mosul (Paris: Institute de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques, 2017), http://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Obs-ProspHuma-Iraq-july-2017.pdf.

36 Samuel Morris, Khogir Wirya, and Dlawer Ala’Aldeen, The Future of Kirkuk: A Roadmap for Resolving the Status of the Governorate (Erbil: Middle East Research Institute, 2015), http://www.meri‑k.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/The-Future-of-Kirkuk-A-Roadmap-for-Resolving-the-Status-of-the-Province-English.pdf.

37 “Yaychi Local Council Denies the Formation of a Turkmen Force in Kirkuk,” NRT, July 18, 2017, http://www.nrttv.com/Ar/Detail.aspx?Jimare=52640.

38 Editorial Staff, “Turkey to Arm Turkmen Forces in Iraq’s Kirkuk, after Military Training,” Ekurd Daily, July 17, 2017, http://ekurd.net/turkey-arm-turkmen-kirkuk-2017 – 07-17.

39 The Kakai Battalion, also known as Yarsan or Ahal al-Haqq, has been caught in the middle of PUK and KDP infighting, with both political parties vying for control of the militia. Saad Salloum, “Iraq’s Kakai Minority Joins Fight against Islamic State,” Al Monitor, September 22, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/09/iraq-kakai-religious-beliefs-armed-force-isis.html. At least one of the Battalion’s three regiments operates in Daquq district (headquartered in Tal Hamma area, close to the Kakai-majority Arab Koi village on the frontlines with ISIL). Mohammed A. Salih and Wladimir van Wilgenburg, “Iraq’s Kakais: ‘We Want to Protect Our Culture’,” Al Jazeera, February 11, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/02/iraq-kakais-protect-culture-150209064856695.html.

40 The group calls itself the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons. It is linked with the military arm of the Kurdistan Democratic Party. The group is led by Hussayn Yazdan Bina, and it is not the same as the homonymous PKK-splinter group based in Turkey, which the US designated as a terrorist group in 2008. Shalaw Mohammed, “Ragtag Kurdish Forces Face ISIL assaults at ‘The Kobani of Iraq’,” Informed Comment: Thoughts on the Middle East, History and Religion, January 23, 2015, https://www.juancole.com/2015/01/kurdish-assaults-kobani.html; “Kurdish Sources: Tehran Wants an Excuse for the ‘Hashd’ to Attack the City to Disrupt the Referendum on Independence,” Asharq al Awsat, June 24, 2017.

41 Kurdistan Regional Government, “KRG Statement on Recent Events at Oil Facilities and Infrastructure in Makhmour District,” Press release, Ministry of Natural Resources. July 11, 2014, http://mnr.krg.org/index.php/en/press-releases/394-krg-statement-on-recent-events-at-oil-facilities-and-infrastructure-in-makhmour-district.

42 “Kirkuk Oil Flows in Jeopardy Again as Kurdish Tensions Grow,” Reuters, March 3, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-oil-kirkuk-turkey-idUSKBN16A1EF.

43 Kamaran al-Najar, Mohammed Hussein, Staff of Iraq Oil Report, “Kirkuk oil crisis subsides as PUK faction withdraws.”

44 Ibid.

45 This parallels patterns in Salah ad-Din’s Tuz district. For more see the summary research profile on Tuz.

46 Although the foreign instructors left the base after graduating the first class, there were reports in February 2016 of three military camps operated by Iranian officers in Kirkuk. Vivian Salama and Bram Janssen, “Tensions are Rising between Kurds and Shia Militias in Iraq,” Business Insider, February 17, 2015, http://www.businessinsider.com/tensions-are-rising-between-kurds-and-shia-militias-in-iraq-2015 – 2?IR=T.

47 Although this was the only base confirmed by this research, a Saudi newspaper reported of additional camps with links to Iran. Dalshad Abdullah, “Six Iranian Military Camps South of Kirkuk… Others on the Way,” Asharq al Awsat, August 22, 2016, https://english.aawsat.com/d‑abdullah/news-middle-east/six-iranian-military-camps-south-kirkuk-others-way.

48 The northern front is under the command of Yilmaz an-Najjar, commonly known as Abu Ridha an-Najjar, who is deputy minister of municipalities. Shalaw Mohammed, “Interview + Kirkuk Militia Spokesperson: ‘We Are Proud to Be Supported by Iran’,” NIQASH, July 4, 2017, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/security/5629/.

49 This area includes Daquq district, Amerli and Suleiman Bek (in Tuz district). Another force, Brigade 16, operates in Tuz Khurmatu city.

50 Each regiment is named after the recruits’ areas of origin: Bashir Regiment, Taza Regiment, Taza Martyrs’ Regiment, Daquq Regiment, al-Qa’im Regiment, and Regiment 90 (“90” is an historic neighborhood in Kirkuk city). The commander of Brigade 16 is Nabeel Issa (nom de guerre: Abu Tha’ir al-Bashiri) from Bashir village.

51 The Martyr Sadr Regiment is a Shi’a Turkmen force under PMF Brigade 15; it was established by the Kirkuk office of the Islamic Da’wa Party (the largest political party in Iraq that has been the source of all prime ministers since 2006). The Haqq Regiment is composed of Sunni Turkmens; it was established by Turhan al-Mufti, an advisor to the prime minister on Turkmen affairs and head of the Turkmen Haqq Party.

52 Although it was not possible for researchers to visit the Arab villages, locals claimed that every force that took part in the operation to retake Bashir is still present in the area as a holding force, including Shi’a Arab forces, although parts of each force has been re-deployed to other governorates or areas of PMF operations.

53 See, for example, Wasfi al-Assi explain to his fighters that they are part of al-hashd al-shaabi, which many accuse of violating the rights of Sunni Arabs. Qasim Jabar, “Sheikh Wasfi al-Assi Talks to Ubayd Tribal Fighters who volunteered with the Hashd,” YouTube video, 1:51, March 12, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFzIdanwSSE; see also Hadi al-Ameri’s visit to the Sunni Hashd: The Hashd — Southwest Kirkuk, Facebook post. April 9, 2017, accessed August 15, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=183108662090223&id=134231490311274.

54 Al Sumaria, “Hawija Hashd: The East Tigris Joint Operations Command Prepares a Plan to Liberate the District,” December 9, 2016.

55 “Sheikh Wasfi Al-Assi Al-Ubaidi Oversees Volunteering for Hawija Hashd in the al-Alam Area,” YouTube video, 2:48, September 16, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJx85HVvOHw.

56 “Nu’aym Chieftain Calls on the Government to Arm the Tribes and Include their Fighters in the Liberation of Kirkuk,” Al Mada Press, July 10, 2016.

57 In a recent meeting in July 2017, the PMF’s commander at the “northern front,” Yilmaz an-Najjar, committed to training and equipping the group to prepare them for the Hawija operation. “Arabs of Kirkuk Demand the Popular Hashd to Include Their Volunteers in the Battle of Hawija,” NRT TV, July 2017, http://www.nrttv.com/AR/Detail.aspx?Jimare=51210.

58 Two units of the Free Iraq Brigade (liwa’ ahrar al-‘iraq) have been based in Jadida village since early 2016 – one of the Arab villages recently recaptured close to Bashir (Taza sub-district).

59 The Free Iraq Division was formally established in 2014 by the Iraqi Fatwa Office, a Sunni religious institution led by Mufti Mahdi bin Ahmed al-Sumayda’i, as part of the popular mobilization against ISIL. “His Eminence the Mufti of the Republic of Iraq Meets the Representative of His Eminence in the Province of Basra,” Iraq Fatwa House, August 14, 2017, http://www.h‑iftaa.com/.

60 See also, “The Formation of a Second Brigade of the (…) Free Iraq Brigade in Kirkuk,” Rudaw, August 10, 2017, http://www.rudaw.net/arabic/kurdistan/100820179.

61 Dexter Filkins, “The Fight of Their Lives,” The New Yorker, September 29, 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/09/29/fight-lives.

62 HRW observed more than 60 villages that appeared to be partially or totally destroyed via satellite imagery (see the map “Building Demolitions in Villages, Kirkuk Governorate”). HRW further corroborated the destruction of 17 of these sites through witness testimony and site visits, which are described in Human Rights Watch, Marked with an “X”: Iraqi Kurdish Forces’ Destruction of Villages, Homes in Conflict with ISIS (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/11/13/marked‑x/iraqi-kurdish-forces-destruction-villages-homes-conflict-isis.

63 Joost Hiltermann, “Iraq: The Battle to Come,” The New York Review of Books, July 1, 2017, http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/07/01/iraq-the-battle-to-come/.

64 HRW, Marked with an “X.”

65 Ibid.

66 Amnesty International, ‘Where Are We Supposed to Go?’ Destruction and Forced Displacement in Kirkuk (London: Amnesty International, 2016), https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/kirkuk_briefing.pdf.

67 HRW, Marked with an “X.”

68 Tim Arango, “ISIS Fighters in Iraq Attack Kirkuk, Diverting Attention from Mosul.”

69 Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch report that hundreds of IDP families were evicted from Wahed Huzairan (June First) and other Arab-majority and mixed-ethnicity neighborhoods of Kirkuk city in a matter of days after the Asayish issued a verbal warning and confiscated identity cards, which would only be returned if the families left Kirkuk. Amnesty International, Where Are We Supposed to Go; Human Rights Watch, KRG: Kurdish Forces Ejecting Arabs in Kirkuk Halt Displacements, Demolitions; Compensate Victims (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/03/krg-kurdish-forces-ejecting-arabs-kirkuk; Human Rights Watch, Marked with an “X.”

70 Amnesty International, Where Are We Supposed to Go; HRW, KRG: Kurdish Forces Ejecting Arabs; Human Rights Watch, Marked with an “X.”

71 Al Hurra Iraq, “The Iraqi Forces Alliance Accuses Kirkuk Authorities of Expelling the Inhabitants of Qarah Tabah Village,” YouTube video, 2:37, October 11, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iipIu3Q_M24.

72 “The Return of the Residents of Qarah Tabah in Parts to Their Homes South of Kirkuk,” Kirkuk Now, March 22, 2017, kirkuknow.com/arabic/. Some reports allege that Qoshqaya and Qotan were razed after their evacuation. “Peshmerga Official: We Have Information Confirming the Cooperation of Some People of Qushqaya and Qutan with Daesh,” Al Sumaria, November 9, 2016.

73 For example, on September 22, 2016, 115 families were evicted from the Laylan IDP camp, and their homes were destroyed. Several Arab IDP families from Hawija were evicted from Kirkuk city as ISIL strengthened its grip on Hawija district. Evictions were carried out by local authorities, aided by the Asayish. Human Rights Watch, KRG: Kurdish Forces Ejecting Arabs. Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen IDPs from outside Kirkuk reportedly comprise the majority of the nearly 374,000 IDPs, according to some estimates.

74 Ibid.

75 Amnesty International, Where Are We Supposed to Go; “Iraq: Kirkuk Security Forces Expel Displaced Turkmen,” Human Rights Watch News, May 7, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/07/iraq-kirkuk-security-forces-expel-displaced-turkmen.

76 “Daesh Expelled from Iraqi Turkmen Village of Bashir, but Village Left in Ruins,” Daily Sabah, May 11, 2016, https://www.dailysabah.com/mideast/2016/05/11/daesh-expelled-from-iraqi-turkmen-village-of-bashir-but-village-left-in-ruins.

77 Hiltermann, “Iraq: the Battle to Come.”

78 An agreement was only reached months later, with the mediation of the top Shi’a cleric’s office.

79 Taei, “Power-Sharing Agreement.”

80 For a more considered discussion of the potential future conflict points in Kirkuk but also more broadly, see Hiltermann, “Iraq: the Battle to Come.”

81 See, e.g., Morgan L. Kaplan and Ramzy Mardini, “The Kurdish region of Iraq is going to vote on independence. Here’s what you need to know,” Washington Post, June 21, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/06/21/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-kurdish-referendum-on-independence/?utm_term=.f85201e42851.

82 For a larger discussion of the PUK and local Kirkuk politicians’ reaction to the referendum, see Hiltermann, “Iraq: the Battle to Come.”