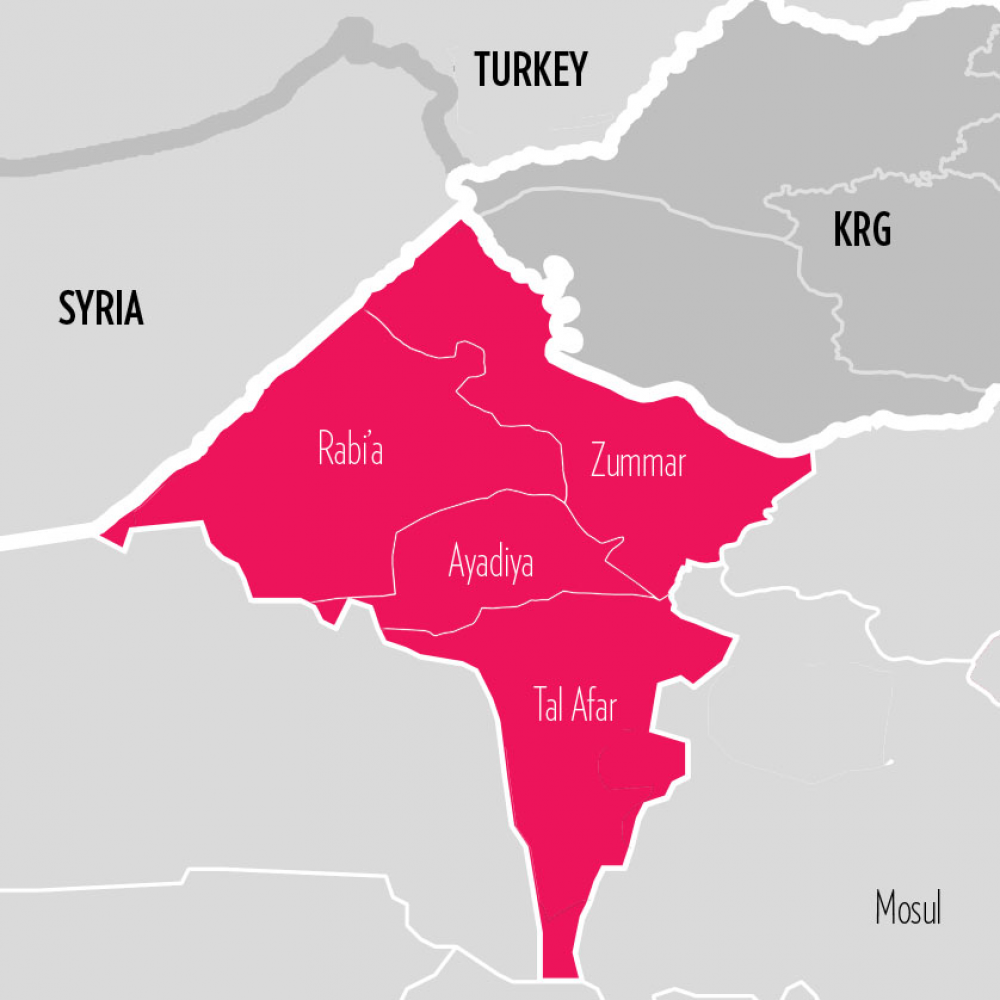

Iraq after ISIL: Zummar

A focal point of Kurdish claims within Iraq’s Disputed Territories, Zummar is now under the firm control of Kurdish forces, with local Arab and Kurdish tribal forces providing additional security support to Kurdish forces; return of Arabs to Zummar has been fraught with controversy.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

Zummar is a rural, mixed-ethnicity, Sunni Arab and Kurd, sub-district of Tel Afar that runs along the western shores of the Mosul Dam Lake – a reservoir on the Tigris that feeds the largest Iraqi dam, forty kilometers north of Mosul.2 Although a Disputed Territory, Zummar was under the Federal Government’s authority until ISIL-captured Mosul in June 2014, which effectively stripped Baghdad from control in Ninewa governorate. Kurdish Security Forces (with support from Coalition air strikes) cleared the sub-district by the end of the year and remain in control to date. Both Kurdish and Arab tribal forces provide auxiliary support to hold the area, but each group has different levels of integration into the formal structures of the Kurdish Security Forces.

In addition to documented instances of property destruction that disproportionally affected Sunni Arabs in Zummar, return of Arabs has also been a controversial issue, and over 7,000 families – one-fourth of the sub-district’s population – remain displaced. Although life seems to have rebounded in Zummar, with functioning markets and high levels of security, Kurdish Security Forces maintain an iron grip over local administration and entry to Zummar. Since Kurdish claims over Zummar are as strong as ever, there seems little appetite to allow Iraqi Security Forces take control of Zummar anew, which could spark confrontation between Erbil and Baghdad in ISIL’s aftermath.

Background

Zummar has been called the “the crux of the territorial dispute in Ninewa” besides Sinjar.3 Zummar sub-district has had a large population of Kurds at least since the 1930s, and experienced some of the first attempts of “Arabization” in Iraq in the 1963 – forced displacement for siding with Kurdish revolutionaries. From the 1970s, Zummar (and parts of Ayyadhiyya sub-district) have endured three decades of systematic anti-Kurd policies, which have ranged from the destruction of villages, confiscation of property, to restrictions in the use of the Kurdish language.

For example, seven entire villages of the Miran tribe (ca. 18,000 people) were moved to Rabi’a sub-district by Presidential decree in 1974. By 1975, approximately 8,500 families were forcibly removed and dozens of villages leveled. In parallel, large numbers of Sunni Arabs moved in to the area, who occupied the lands and took over jobs, including at the Ayn Zala oil field, directly south of Zummar town, which had been operated by Kurdish oil workers.

During the construction of the Mosul dam in the 1980s, large plains of agricultural land, and eight Kurdish villages (and two Arab villages) were flooded; Zummar town was relocated a few kilometers south to its current location. Despite paying a high price for the dam’s construction, a major irrigation project tied to the Mosul dam, the al-Jazeera Project, has not benefitted Zummar’s agriculture; it only passes through the sub-district to reach the lands of Arabs of the Shammar tribe in neighboring Rabi’a sub-district who were intended as the Mosul dam’s and the irrigation project’s main beneficiaries.

Key Facts: Zummar

Population: 168,000

Ethnic Composition: Sunni Arab (majority) and Kurdish (minority)

Date taken by ISIL: August 2014

Date reclaimed: October-December 2014

Forces engaged: Peshmerga (KDP), Asayish (KDP), Coalition air support, with limited support from local informants and the Rojava Peshmerga.

Overall Control: KRG-SF

LHSFs present: Kurdish tribal force (auxiliary), Jazeera Brigade of the Peshmerga (Sunni Arab tribal force)

Key Issues:

- Extended KRG control over a Disputed Territory, with evidence of forced demographic changes

- Local tribal forces as standalone auxiliary forces vs. integrated in the Peshmerga

ISIL Takeover and Expulsion

Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) Security Forces first took control of Zummar sub-district after ISIL took swathes of northern Iraq in early June 2014, prompting the collapse of Iraqi Security Forces in Ninewa and mass displacement. As a relatively safe area at the time, Zummar sub-district hosted 4,000 IDP families by the end of June: two-thirds fled from neighboring areas in Tel Afar district; the rest came from Mosul.4

ISIL launched a major offensive in northern Iraq on August 2, 2014, and drove Kurdish Security Forces out of Zummar, Sinjar, and Wana – a town that hosts the fragile Mosul dam.5 Kurdish Security Forces recorded 14 Peshmerga dead in Zummar.6 ISIL also captured the Ayn Zala oil field, directly south of Zummar town, which has about 40 oil wells with a maximum capacity of 10,000 barrels per day (bpd).7 According to Kurdish security representatives, ISIL built an explosives factory and operated a training camp in its local headquarters in Barzan, a Sunni Arab village 10 km northwest of the sub-district’s capital, which news outlets describe as a stronghold of al-Qaeda since 2003.8 As in other areas included in this research, ISIL targeted local officials, policemen, and members of the parliament first. Zummar’s police chief was immediately beheaded.9 A mass-grave discovered close to Barzan gives testament that civilians were also targeted by ISIL, including Yazidis who had worked as guest workers in a nearby construction. According to the IOM, one-half of the sub-district’s population fled during this time.10

The Peshmerga mounted a counter-offensive already in August, with support from Coalition air strikes, the Asayish, and local informants. Kurdish Security Forces recaptured the sub-district’s capital on October 25, 2014, and established control over the entire sub-district later that year, with additional support from the Rojava Peshmerga, a Syrian Kurd force trained and equipped by the KDP-led Peshmerga.11 In its retreat, ISIL set three oil wells alight at Ayn Zala,12 and littered the sub-district with booby traps and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

A major criticism levied against Kurdish Security Forces in Zummar is the comparably high degree of destruction in Sunni Arab areas. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented that two Arab-majority villages, Barzan and Shikhan (which were seen en-route to Zummar in February 2017) were reduced to ashes and rubble, and the houses and shops of Arabs were torched in the mixed-community Zummar town and Bardiyya village.13 Amnesty International alleged that local Kurds and/or the Peshmerga have torched and blown up the houses of Arabs in revenge for their support for ISIL, citing also an admission by two local Kurdish commanders interviewed in a Dutch TV program.14 Similar to the three villages destroyed in Rabi’a, key informants have confirmed that Kurdish Security Forces destroyed Arab property in four towns in Zummar sub-district in retaliation for their alleged support for ISIL: Barzan, Shikhan, Kar-kafer, and Ahmed Agha Fuqani. A survey conducted by IOM in Iraq shows that 94 percent of returnees claimed their property was damaged and though they attached responsibility primarily to ISIL, about 40 percent fear reprisal against him/herself or the family in an area under firm Kurdish control. This is the highest number by far in the eight analyzed geographic areas.15

Kurdish security officials rejected these claims (as did KRG officials in their response to the findings of the international watchdogs), instead claiming that the destruction was a result of Coalition air strikes. Additionally, they noted the extraordinary amount – 222 tons – of explosives left behind in these villages by ISIL, which also caused the death of 24 members of the Kurdish demining team. The author received video footages of the demining operation in the sub-district, with several houses seemingly booby trapped, but the validity of the videos could not be confirmed. However, a storage house in the center of Zummar town had an impressive amount of disarmed IEDs on display during a visit in February 2017.

Security Forces in Zummar

The headquarters of Kurdish Security Forces west of the Tigris, which includes all KRG-controlled parts of Tel Afar district, is in Zummar town. Similar to neighboring Rabi’a and Ayyadhiyya sub-districts, all Kurdish Security Forces in Zummar are tied to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). The Peshmerga is in charge of protecting the borders and is heavily deployed to the southern front with ISIL in Ayyadhiya sub-district, where it was subject of frequent mortar attacks by ISIL at the time of research.

Since recapturing territory in Zummar, the Peshmerga has recruited a 2,000-member auxiliary defense force from local Kurdish tribes, including, among others, the Gergeri,16 Hasniani, Miran, and the Tai. This Kurdish tribal force is deployed to patrol the border with Syria in the north (including the seven Kurdish villages in neighboring Rabi’a sub-district), and the frontline with ISIL in the south. Members of the force received training by the KDP-led command in Dohuk, but they were not integrated into the formal structure of Kurdish Security Forces. There are no reports indicating that the Rojava Peshmerga is present in Zummar sub-district since ISIL’s ouster.

Within the sub-district’s borders, the Asayish is in charge of security, including counter-crime and ‑terrorism. Since 2017, the Asayish is supported by the 2,000-strong Jazeera Brigade, a tribal component of the Peshmerga that draws from local Sunni Arab tribes of Rabi’a, Zummar, and Ayyadhiyya sub-districts, including the Jibbour, Juhaysh Mu’amara, Sharabi, and Shammar tribes. The main objective of the Jazeera Brigade is to provide security in the areas west of the Tigris that were cleared and now controlled by Kurdish Security Forces.17 The Brigade’s first 1,000 fighters,drawn from Zummar and Ayyadhiya, graduated in February 2017. A second tranche, drawn mostly from Rabi’a, graduated in June 2017.18 Despite reports of the Jazeera Brigade’s mobilization to support the Rojava in spring 2017 as it clashed with supporters of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) in Sinjar, key informants claimed that the Jazeera Brigade has not been functionally deployed as its members do not yet undertake any security tasks (an Arab volunteer met at the Asayish office in Zummar joined the KDP-led Peshmerga Unit 80 before the formation of the Jazeera Brigade). Indeed, the establishment of this force has only served so far to co-opt Arabs in areas controlled by Kurds.

A survey conducted by IOM indicates high levels of satisfaction with the Peshmerga and Asayish in Zummar among returnees.19 Similarly, Arab tribal elders from Zummar and Ayyadhiyya sub-districts praised the Peshmerga for shedding their blood,“the biggest sacrifice,” to liberate their homes; however, the sheikhs were interviewed in the presence of the Asayish chief, and no other community representative could be consulted.

Zummar’s Future: Returns, KRG Control, and Oil

Many of the security and political dynamics observed in Rabi’a played out in parallel in Zummar. Notably, the KRG has projected its soft power by providing security and establishing a local tribal force, which gives dignity to locals by taking matters in their hands, and it is an important source of employment in an agricultural area that has had limited access to markets for years.

Arab politicians in Ninewa have realized that a Kurdish-engineered local force could sway public opinion in areas of disputed control and Member of Parliament Abd al-Rahman al-Luwayzi called the establishment of the Jazeera Brigade an attempt by KRG President Masoud Barzani to unlawfully extend his control over areas outside Kurdistan.20 However, such criticism might be too little, too late. Community interviews in Rabi’a have shown support for the force and in May 2017 Mzahim al-Huwait, the spokesman of Arab tribes and a key figure in establishing the Jazeera Brigade, announced that all areas liberated by KRG Security Forces west of the Tigris would join an independent Kurdish state.21 For now, it remains to be seen how strong this alliance between Ninewa Arabs and the Kurdish administration is, and whether Sunni Arab fighters affiliated with Erbil would shoot their brethren wearing Federal Government uniforms in the event of a confrontation with Baghdad.

Aside from the above-mentioned similarities in co-opting Arabs, Kurdish aspirations of long-term control are tangibly different in Zummar from Rabi’a. In Rabi’a, the KRG refrained from intervening in local politics and allowed the large-scale and immediate return of displaced Arab populations even if there are some who continue to be barred from entry. By contrast, the KRG has kept a firm grip on Zummar, which is “the crux of the territorial dispute” in the area, as noted above.22 Three issues illustrate why the KRG’s aspirations in Zummar might be longer-term and resemble patterns observed in Kirkuk, rather than Rabi’a.

First, return of Arab citizens was eased only following strong criticism by international observers, and the issue remains largely unresolved. In early 2015, Human Rights Watch reported that in mixed-ethnicity Bardiyya, Garbir, and Zummar towns, displaced Kurds from villages further south were occupying the homes of Arabs, who expected that Arabs, unlike Kurds, would not return.23 A year on, Amnesty International reported that Arab residents were barred from entry, even though displaced Kurds had returned to their homes weeks after ISIL’s ouster.24 In response to these criticisms, Dindar Zebari, a KRG official responsible for the follow-up of international reports, announced in June 2016 that 2,000 Kurdish and Arab IDPs had returned to their homes in Zummar town, but he did not specify the share of each ethnic group.

According to the IOM, one-fourth of Zummar’s pre-ISIL population or about 42,000 individuals, lived in displacement in late 2016, whereas roughly the same amount of people returned already in 2014. Although the IOM does not disaggregate the data based on ethnicity, these displacement patterns match allegations made by human rights observers about the quick return of Kurds to Zummar and the continued displacement of Arabs. According to a survey included in the same study, two-thirds of IDPs expressed their intention to return, but highlighted the potential of increased inter-communal tensions as result of returns to Zummar.25 In stark contrast to the IOM’s findings, Zummar’s mayor claimed that 95 percent of displaced populations returned to Zummar in October 2016.26

Second, local administration is tightly controlled by Kurdish Security Forces in Zummar. Meetings of the heads of local departments are held in the office of the Asayish chief27 and a KDP-member was appointed as mayor of Zummar in 201528 even though the office should be elected by members of the local council. Unlike in Rabi’a, Kurdish Security Forces have closely monitored the author’s movement and interactions with locals, which is why only limited information could be collected about the impact of local, hybrid and sub-state security forces (LHSFs) on community dynamics in the sub-district. Moreover, a head of one of the Kurdish Security Forces had asserted that those accused of committing crimes must be brought before the Dohuk Criminal Court: an indication that Zummar sits under the authority of the KRG, and not under the Government of Iraq in Ninewa. An expert familiar with local dynamics added, “Everyone knows in Rabi’a, Zummar, and [parts of] Sinjar, that the true ruler is the governor of Dohuk and not the governor of Ninewa.”

Third, Kurdish control over the Ayn Zala oil field is not only an important source of income in times of war, but a building block of Kurdish economic independence. The KRG is not likely to let go of such a prize even if, with its current output of 2,000 bpd and maximum capacity of 10,000 bpd, Ayn Zala compares modestly to other oil fields captured by Kurdish Security Forces after June 2014 (notably, two large fields in Kirkuk, which together produce about 150,000 bpd).29 Although Iraq’s state-run North Oil Company is still formally in charge of Ayn Zala, the KRG trucks the oil to Fishkhabour, a border town, where it blends it with the crude arriving from Kirkuk, and feeds the oil into the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline that runs to the Turkish port of Ceyhan – the KRG’s principle point of access to international markets.30

References

1 This research brief draws primarily on a brief field research visit to Zummar town, and secondary sources and international monitors tracking trends in Zummar. Access to locations outside Zummar city was denied during the field visit, but two destroyed Arab villages, Barzan and Shikhan, were spotted along the main road to Zummar – a phenomenon well-documented by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. James Barklamb provided research support.

2 Dexter Filkins, “A Bigger Problem than ISIS?” New Yorker, January 2, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/02/a‑bigger-problem-than-isis. The sub-district’s historic capital was flooded during the dam’s construction; the new Zummar town was built in the 1980s.

3 Sean Kane, Iraq’s Disputed Territories. A View of the Political Horizon and Implications for U.S. Policy (Washington, DC: United States Institute for Peace, 2011), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PW69_final.pdf.

4 REACH, IDP Factsheet: Zummar City, Ninewa Governorate, Iraq (Geneva: REACH, 2014), http://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/idp-factsheet-zummar-city-ninewa-governorate-iraq-data-collected-24 – 26-june-2014.

5 Tim Arango, “Sunni Extremists in Iraq Seize 3 Towns from Kurds and Threaten Major Dam,” New York Times, August 3, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/04/world/middleeast/iraq.html.

6 “Jihadists Kill Dozens as Iraq Fighting Rages,” Al Arabiya English, August 2, 2014, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2014/08/02/Army-Jihadists-kill-30-in-fighting-south-of-Baghdad-.html.

7 Iraq Oil Report staff, “KRG Solidifies Hold on Ain Zalah,” Iraq Oil Report, March 26, 2015, http://www.iraqoilreport.com/news/krg-solidifies-hold-on-ain-zalah-14284/.

8 “Exclusive: The Fierce Battle for Iraq’s Zumar,” Al Jazeera, September 25, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/video/middleeast/2014/09/exclusive-fierce-battle-iraq-zumar-201492510442185799.html.

9 Richard Spencer, “Ghost Villages of Northern Iraq Ripped Apart by ISIL Jihadists,” Telegraph, October 5, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iraq/11142115/Ghost-villages-of-northern-Iraq-ripped-apart-by-Isil-jihadists.html.

10 International Organization for Migration, Obstacles to Return in Retaken Areas of Iraq (Baghdad: International Organization for Migration (Iraq Mission), 2017), http://iraqdtm.iom.int/SpecialReports/ObstaclesToReturn06211701.pdf.

11 For more information, see on Rojava Peshmerga, see the research summary onRabi’a; “Peshmerga Forces Control Areas in Iraqi Zumar, Peshmerga and Ruj Ava Participate,” ARA News, December 19, 2014.

12 “Peshmerga, IS Battle for Zumar,” Rudaw, August 8, 2014, http://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/30082014.

13 Human Rights Watch, Iraqi Kurdistan: Arabs Displaced, Cordoned Off, Detained (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2015), https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/02/25/iraqi-kurdistan-arabs-displaced-cordoned-detained; Amnesty International, Northern Iraq: Satellite Images Back up Evidence of Deliberate Mass Destruction in Peshmerga-Controlled Arab Villages (London: Amnesty International, 2016), https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/01/northern-iraq-satellite-images-back-up-evidence-of-deliberate-mass-destruction-in-peshmerga-controlled-arab-villages/.

14 AI, Northern Iraq.

15 IOM,Obstacles to Return.

16 The Gergeri are Arabized Kurds who live mostly south from Zummar (south of the Mosul-Rabi’a road). They were allowed to stay in their areas during the Arabization campaign in the 1970s, but lived with a number of restrictions; for example, they could not give Kurdish names to their children.

17 “Peshmerga Graduates the First Class of Arab Volunteers from Ninewa,”Al Jazeera, August 2, 2017.

18 A key informant claimed that President Barzani has identified the Jazeera Brigade’s inclusion of 500 Kurdish fighters as a means to counter tribal enmity and enable different ethnic groups to overcome their differences and fight together for their lands, but the presence of Kurdish fighters within the Jazeera Brigade has not been confirmed by others.

19 IOM, Obstacles to Return.

20 “A New Batch of Peshmerga Graduates from Arab Volunteers in Mosul,” YouTube video, 2:34, posted by “Alhurra Iraq,” June 20, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMyxiKigpOA.

21 Dilshad Abdallah, “Arab Tribes of Ninewa Announce Their Support for Kurdish Independence,” Asharq al-Awsat, May 13, 2017.

22 Sean Kane, Iraq’s Disputed Territories.

23 HRW, Iraqi Kurdistan.

24 AI, Northern Iraq; According to a Reuters report, 50 Arab families were allowed to return to Zummar town as of September 2016. Isabel Coles and Stephen Kalin, “In Fight against Islamic State, Kurds Expand their Territory,” Reuters, October 10, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/mideast-crisis-kurds-land/.

25 IOM, Obstacles to Return.

26 “95% of IDPs from Zummar in Northern Mosul Have Returned Home,” Bas News, October 26, 2016, http://www.basnews.com/index.php/en/news/iraq/307403.

27 Radio Zummar’s Facebook page, accessed August 4, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/radio.zummar/posts/1076470142455924.

28 AI, Northern Iraq.

29 In 2015, Ayn Zala operated at 2,000 bpm, partly due to the shortage of workforce related to the displacement of Arabs from the area. According to an engineer in charge of the operation asked by Reuters, the “workforce has fallen by around half because many Arab employees either joined [ISIL] or are trapped in their territory. As a result, around 60 percent of workers are now Kurdish, up from 20 percent before Islamic State. Iraq Oil Report staff, “KRG Solidifies Hold”; Coles and Kalin, “Fight against Islamic State.”

30 Patrick Osgood and Ben van Heuvelen, “Oil from Kurdistan Pipeline Enters Turkey,” Iraqi Oil Report, December 14, 2013, http://www.iraqoilreport.com/news/oil-kurdistan-pipeline-enters-turkey-11628/.