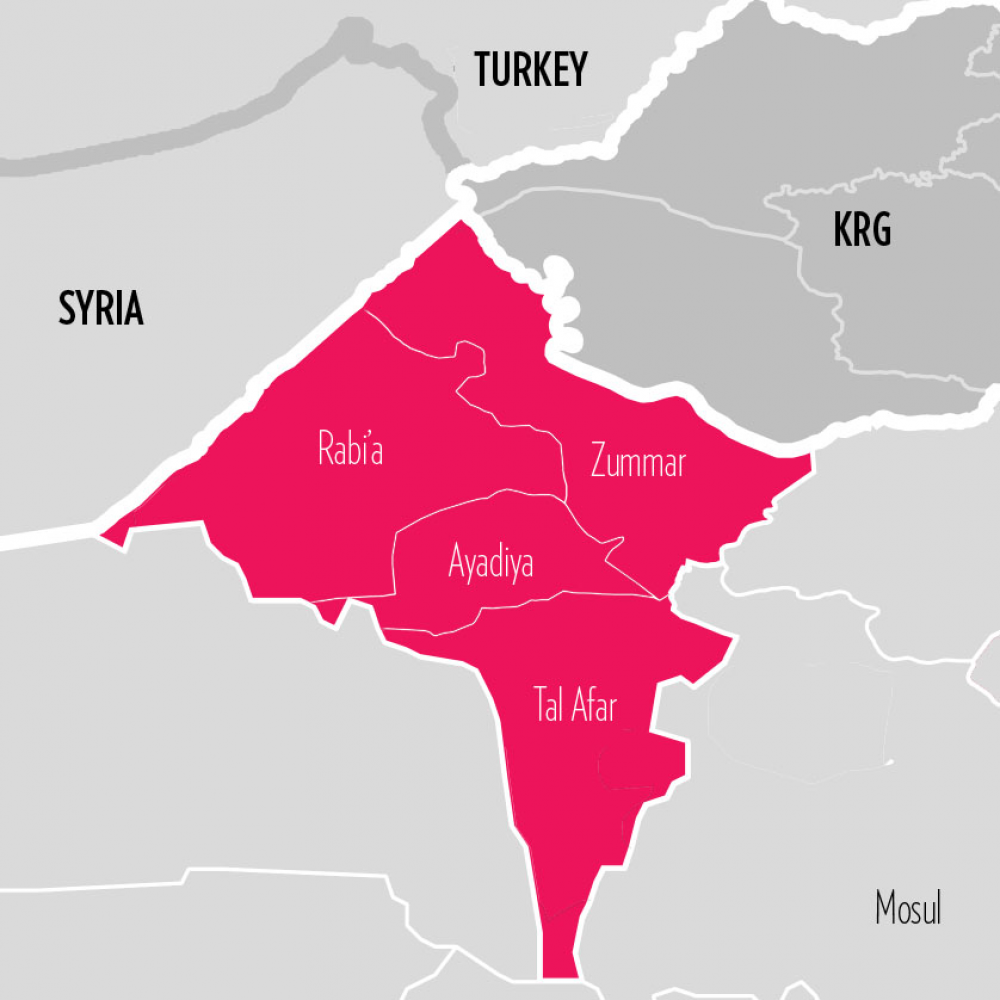

Iraq after ISIL: Rabi’a

A test of the Disputed Territories boundary line, this predominantly Sunni Arab area in Tal Afar district has flipped to Kurdish control after ISIL’s ouster, and local tribal forces have formed units under KDP Peshmerga.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

Rabi’a is a middle-sized, rural, and largely homogenous Sunni Arab sub-district of Tal Afar that runs along the Syrian border in the northwestern corner of Iraq. Although Rabi’a holds oil reserves, its geographic location, rather than its economy, lends it strategic importance. The sub-district connects the heartland of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to the east with Sinjar district to the west, and Rabi’a town – the sub-district’s center – has a border crossing with Syria. Unlike neighboring Zummar or Sinjar, however, Rabi’a is not considered part of Iraq’s Disputed Territories; the Iraqi security forces and the civil administration in Mosul were in exclusive control of the area until ISIL took charge in June 2014.

In August 2014, Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) security forces entered and in the course of a few months cleared Rabi’a, which led to the rare situation of effective Kurdish control over a non-disputed area (similar to Zummar, there are allegations of deliberate destruction of Arab property by KRG Security Forces). Rabi’a is also unique in contributing large cohorts of tribal forces to newly-established combat units under different command structures – the Government of Iraq and the KRG – which showcases local-level dynamics and incentives related to their establishment. Moreover, Rabi’a is home to Syrian fighters, either as part of the KDP-affiliate Rojava Peshmerga or the all-female counterpart of the YPG, the Kurdish Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), whose snipers oversee Rabi’a town from a silo on the Syrian border. Despite the conflict in Sinjar and anti-ISIL operations in nearby parts of Ninewa governorate, Rabi’a remains stable. However, as the focus of Iraqi forces shifts toward ISIL-held Tal Afar following their expulsion from Mosul in early July 2017, Baghdad will likely raise expectations about the “return” of Rabi’a from Kurdish control.

Key Facts: Rab’ia

Population: 86,000

Ethnic Composition: Majority Sunni Arab, with few Kurdish villages and Sunni Turkmen IDPs

Date taken by ISIL: June 2014

Date reclaimed: October – December 2014

Forces engaged: Peshmerga (KDP), Asayish (KDP), Coalition air support, with limited support from local tribal informants and YPJ

Overall Control: KRG-SF (KDP)

LHSFs present: Jazeera Brigade of the Peshmerga (Sunni Arab tribal force), Rojava Peshmerga, Kurdish Women’s Protection Units (YPJ)

Key Issues:

- Expansion of KRG authority in “non-disputed” area

- Sunni Arab tribal forces under GOI vs. KRG command

- Presence of Syrian Kurd forces

ISIL Takeover and Expulsion

As Mosul fell in June 2014, the Iraqi army and the local police, with no top-level command to report to, collapsed in Rabi’a sub-district. The next day, ISIL effectively took control of Rabi’a town by establishing a checkpoint that, despite being manned by only four fighters, remained unchallenged.

ISIL fighters in Rabi’a were largely local, as in other districts included in the research. The group reportedly also included scores of Sunni Turkmen IDPs who had settled in Rabi’a after 2006, fleeing violence in Tal Afar. In September 2014, the head of the second-largest tribe in Rabi’a, the Juhaysh, asked all tribal leaders to come to his house in Moumi to pledge allegiance to ISIL.2

ISIL’s appearance in Rabi’a was not a surprise, even if the Shammar tribe, which constitutes 80 – 90% of the sub-district’s population of 86,000, has traditionally supported all post-Saddam Iraqi governments and fought al-Qaida alongside the US. The Shammar hold key positions in Rabi’a; the mayor, the city manager, eight of the 10 local council members.3 and the head of local police belong to that tribe.4 A local elder pegged the blame for not resisting ISIL on Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who had allegedly confiscated the weapons of all tribes living close to the border in early 2014, leaving them powerless against the group.

An investigative journalist revealed, based on intelligence sources, that ISIL had controlled the import of goods from Syria through the international border crossing in Rabi’a town well before taking Mosul and that it had levied a US$300 – 600 tax on each commercial truck passing through.5 This scenario was possible because ISIL had, for some years, planted eyes along the international highway connecting Rabi’a to Mosul to observe freight transport and set up ambushes against military convoys.6 In addition, locals alleged that ISIL had used Juhaysh-majority villages in Rabi’a and Ayyadhiyya as safe havens and launching pads to attack Yazidis in neighboring Sinjar district since 2011 – similar to how ISIL has drawn support from the Sunni Turkmens of Tal Afar.

Half of Rabi’a sub-district’s population fled before and during ISIL’s control. Many settled in Kurdish-controlled areas in the east (e.g., Dohuk, Erbil), others in areas controlled by the Federal Government, but a significant proportion of the population fled immediately across the border into Syria. The head of the local council noted that he, his family, and all of the council’s sitting members fled into Syria when ISIL took control. The headquarters of the local police force and three other police stations in the sub-district were destroyed, as were all holding facilities.

KRG Security Forces, aided by US and UK air strikes,7 cleared Rabi’a town on October 2, 2014, after a fierce, 48-hour-long battle to clear the road toward Sinjar. ISIL had been committing genocide against Yazidis there, stranding them on barren Mount Sinjar in August, among other atrocities. Local tribesmen provided information to Kurdish forces leading the operation but did not engage directly in combat.8 Locals also give credit to the Kurdish Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) for having shot dozens of ISIL operatives up at the unfinished Rabi’a general hospital building, which is across from their sniper lookout on top of a silo at the Syrian border. Although Rabi’a town was liberated relatively quickly, ISIL retained control of the surrounding rural areas, which have comparably less strategic importance, and the entire sub-district was not fully under Kurdish control until December 17 – 19, 2014.

Besides the destruction brought by ISIL, most damage to property resulted from artillery fire as the front line shifted through Rabi’a town and more than 20 of the 82 villages in the sub-district. There was little damage to civilian property observed in Rabi’a town during a visit in February 2017, but the houses of the hundreds of Sunni Turkmen IDP families who all fled after ISIL’s expulsion looked derelict. Four villages northeast from Rabi’a town, Mahmoudiyya, Qahira, Saudiyya, and Sfaya were largely destroyed, reportedly by Kurdish forces. This level of property destruction is similar to that in neighboring Zummar.

Security Forces in Rabi’a

Since taking control in 2014, the KRG Security Forces have largely stabilized Rabi’a. According to a local police officer interviewed in February 2017, the sub-district is completely safe, with the exception of a few Juhaysh-majority villages close to Sinjar, which might experience sporadic retaliatory attacks by Yazidis. He added that crime levels were also down because the “troublemakers” had joined ISIL and fled after its expulsion.

The KDP-Peshmerga in Rabi’a include two unusual components. First, at the time of a visit to Rabi’a in February 2017, the Rojava Peshmerga were manning smaller checkpoints along the main route from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to Sinjar and were later mobilized to Sinjar to engage Yazidi Protection Units affiliated with the YPG.9 KRG President Masoud Barzani established the Rojava Peshmerga in February 2012 in an attempt to create a KDP-friendly Kurdish force in Syria. By September 2015, the Rojava Peshmerga’s two brigades had 3,000−4,000 fighters, trained by the Peshmerga and, more recently, Coalition forces.10 The Rojava reports to the Peshmerga’s special forces, the Zeravani.11 Because the YPG have denied the Rojava access into Syria out of fear that their presence would cause a split in Syrian Kurds like the one between the PUK and KDP in Iraq, this Syrian Kurd force was deployed in Iraq against ISIL as part of the KRG Security Forces. The presence of the YPG’s all-female equivalent, the YPJ at the silo, and their alleged control of the customs have not caused open confrontation to date.

Second, the KDP-Peshmerga has established a 2,000-strong tribal force in the areas that have come under exclusive KRG control since September 2014: Rabi’a, Zummar, and Ayyadhiya sub-districts of Tal Afar. The Jazeera Brigade reports to the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs and includes two Sunni Arab battalions of 1,000 fighters each. According to a statement by the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, the primary task of these tribal forces is to hold their ancestral lands, which were cleared by Kurdish security forces, and to foil future incursions.12 Rather than through active combat, the Jazeera Brigade helps stabilize an area by gathering intelligence from locals on the behest of the KRG Security Forces.

The head of Kurdish security forces on the Zummar-Rabi’a front, Colonel General Za’im Ali, agreed that the biggest asset of the tribal forces is their local knowledge and valor in protecting their lands (which also prevents them from joining extremist forces), but he also hinted at possible deployments to the front lines. Similarly, Sheikh Fahd Khalaf Jasim, the tactical leader of the second Arab battalion, claimed his troops could engage in combat in areas outside Rabi’a, such as Sinjar district. This move would lead to a very delicate situation because Shammar tribal forces in Sinjar are allied with the KDP’s fierce enemy, the Sinjar Resistance Units, a Yazidi force alleged to be loyal to the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK).13 When asked, Sheikh Fahd claimed he would follow the KDP-Peshmerga’s orders without hesitation, even though “[he] will surely be labeled Barzani’s puppet.”

Like the Rojava, the Jazeera Brigade reports to the Zeravani and has been trained and equipped by the Peshmerga and Coalition forces at the Khanas camp in Ninewa’s northeastern Sheikhan district. Training lasts 40 days; fighters then receive a 10-day break before being mobilized to their assigned area of responsibility, explained Sheikh Fahd. The first Arab battalion – composed mainly of the Juhaysh, Muamara, Sharabi, and Jibbour tribes – graduated in February 2017, and some were deployed in March 2017 to Sinjar to reinforce the Rojava Peshmerga forces that clashed with PKK-sympathizers near Khana Sur town. Most of them, however, took up duty in Zummar and Ayyadhiyya sub-districts. The second battalion, called al-Ajeel Battalion, graduated in July 2017, and is composed mostly of Shammar and other tribesmen from Rabi’a.14

All interviewed community representatives claimed that relations between the KRG Security Forces and locals were good, and many had close relatives who had recently enlisted in the al-Ajeel Battalion. While the preference for local security actors is not surprising, the indifference to whether tribal forces report to Baghdad or the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs in Erbil shows a rift in what was known as an area deeply loyal to the Federal Government, even if many expressed a preference for shared control of the sub-district’s borders between the Iraqi army and the Peshmerga.

The KRG’s control in Rabi’a is unique because the sub-district is not considered a “disputed territory” that would fall under the provisions of Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution. As such, Kurdish forces operate next to Baghdad structures. For example, the local council and the local police continue to report to Mosul. In practice, then, the Asayish is the main counter-terrorism and counter-crime entity, but it often investigates cases together with the local police because of its knowledge of local customs and people, explained a Rabi’a‑based police officer while showing gestures of walking side-by-side.15

Tribal Mobilization Forces were also briefly established in Rabi’a. In March 2016, Member of Parliament Ahmed Madlul al-Jarba announced an agreement with the KRG and Baghdad (and donated US$25,000) to establish the West Ninewa training center in Abu Hujayra village and form a tribal mobilization force (hashd al-asha’ir) called the Ninewa Lions. The Ninewa Lions would be tasked with clearing ISIL-controlled areas primarily in Ninewa governorate, including its remote western areas such as Ba’aj district.16 The tactical leader of the force, Sheikh Fahd Khalaf Jasim saw the agreement as a recognition of his earlier success training a Shammar tribal force in Syria, Hashd al-Nawadir.17

Although MP al-Jarba announced receiving authorization to train 1,500 fighters18 and Sheikh Fahd said he amassed 2,000 under his command, only 600 fighters could be formally enlisted and placed on salary.19 He said his fighters received training and light equipment through the TMF program and were trained at West Ninewa Camp by Coalition forces (notably including Spanish forces), which was confirmed through Coalition sources. However, the West Ninewa camp was closed in November-December 2016 due to frictions with the Iraqi government. The Iraqi government, in coordination with KRG, deployed the 600 tribal fighters to Mosul airport in early 2017, who then participated in the recapture of Mosul under the command of the Federal Police according to a key informant.20 Frustrated by the low numbers and poor equipment of the enlisted Ninewa Lions, Sheikh Fahd submitted in early 2017 the names of 1,000 fighters to the KDP-Peshmerga for security checks to form an Arab Peshmerga Brigade within the Jazeera Force (see above).

Post-Liberation Challenges and Security Outlook

All consulted stakeholders claimed that life is getting better in Rabi’a. The area is relatively stable; there is electricity for at least 12 hours a day; and many locals have started repairs on their damaged property. The central government (or the KRG) has not provided any support for reconstruction as of May 2017, which is why many public buildings show signs of damage. Some offices have found temporary locations; for example, the local police is headquartered in the former town club house. Humanitarian organizations are active in Rabi’a (e.g., the International Committee of the Red Cross supports the health directorate, and it restored a key borehole in Rabi’a town in 2015 to open access to clean water), but many have now shifted their attention away from Rabi’a to more-recently cleared areas in Ninewa governorate, such as Mosul city.

According to local officials, about 96% of displaced Rabi’a locals had returned by early 2017, with only 950 families living in continued displacement within or outside the sub-district’s boundaries. In May 2017, four of the five interviewed IDPs claimed they would move back home in a matter of weeks, which suggests a virtual end to displacement in Rabi’a. There are only four villages where return was not permitted in February 2017 (Mahmoudiyya, Qahira, Saudiyya, and Sfaya) and which are the same localities that experienced large-scale destruction of property during or after the military campaign. According to key informants, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) announced in July 2017 that all IDPs residing in the Kurdistan Region might return to Rabi’a; however, IDPs who settled in Syria and areas controlled by the Federal Government might not. The plan has not yet been implemented.

About 850 families registered as IDPs in Rabi’a sub-district in February 2017 had been displaced from neighboring areas. The largest group were Sunni Arabs of the Juhaysh tribe, who were uprooted from 56 villages in Sinjar by Yazidis in what many see as retaliatory acts for Juhaysh support for ISIL. Shammar leaders in Rabi’a are advocating for their return to Sinjar but also highlighting that reconciliation will require coordination and logistical support from international organizations, including, for example, the al-Tahreer Association.21

Similar to other KRG-controlled areas, the Asayish is ultimately responsible for running security checks on incoming IDPs and returnees. The vetting procedure is usually initiated by the mukhtar, who collects information about newly-arriving people on a form and informs the local council and the mayor, besides the Asayish. Tribal security guarantees are necessary when persons or whole communities are accused of supporting ISIL. For example, members of the Sharabi tribe were only approved by the Asayish after the Shammar provided security guarantees on their behalf. Similarly, it took sustained advocacy efforts by the local council and tribal representatives to convince the Asayish to let 60 displaced Iraqi families back to Rabi’a. These families were stranded in the Rabi’a customs house on the Syrian border for months from the end of 2016 because Kurdish Security Forces suspected their association with ISIL, questioning their motivations for waiting two whole years after ISIL’s expulsion from Rabi’a to return from Syria’s al-Houl IDP camp.

Other challenges remain. Access to healthcare in Rabi’a is hindered by a limit imposed on the import of medicine and a requirement for special permits to visit better-equipped hospitals in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Many felt restricted in their movements because the road to Mosul was still not open at the time of writing this paper and because access to Syria and to Kurdistan was tightly controlled. Since 2015, the Kurdish authorities have enforced firm restrictions on trade between Kurdistan and Rabi’a on the suspicion that fertilizer would be smuggled across the border and sold to YPG to build explosives for use against KDP-affiliated forces in and outside of Iraq. Limitations on the import of other commodities in demand in Syria, such as slaughtered sheep, rice and sugar were only lifted in spring 2017. Notably, many of the returnees cite the absence of effective water irrigation systems as one of the most significant challenges because it impedes agricultural production and negates their lifestyle.

A fundamental question regarding stability in Rabi’a is how it will fare in the struggle between Baghdad and the KRG. Although locals have traditionally good relations with Baghdad, they are also highly appreciative of the security provided by Kurdish forces. The KRG also outperformed Baghdad in establishing a functioning – trained, equipped, and deployed – local tribal force. When asked about the Kurds, locals highlighted their historically good relations, recalling that the Shammar rejected Saddam Hussein’s plan to “Arabize” the seven Kurdish villages in the northeastern part of the sub-district and that the KRG would only let the Shammar of all Sunni Arab tribes cross into Kurdistan to graze their herds in times of drought.

However, community perceptions in general do not yet favor Kurdish control of Rabi’a. Arab-nationalist identity runs deep among locals, and many see the KRG as only a temporary solution, expressing a preference for a strong Iraqi state. An elder in Gabran village said, “given the situation right now… we prefer to deal with the [Kurds] than face the threat of the Shi’a militias,” who had brought destruction on his kin in Ninewa’s Ba’aj district.22 With the military operation officially over in Mosul, Iraqi Security Forces will soon tackle the two large, remaining pockets of ISIL rule in Iraq: Hawija district in Kirkuk and Tal Afar district in Ninewa. Control over Rabi’a will likely turn into a hot topic as a result.

References

1 The research builds on 13 expert interviews with security, community, and political representatives conducted in Rabi’a, Gabran village (Rabi’a), Zummar, and Dohuk by Andras Derzsi-Horvath and Erica Gaston in February 2017. In addition, a local researcher conducted 10 community interviews in Rabi’a sub-district and five interviews with Rabi’a IDPs in May 2017. Faysal Younis provided invaluable facilitation support, and James Barklamb provided secondary research support.

2 Such public declarations of allegiance were commonplace in ISIL-held areas, and tribal elders had little choice but to fight or flee: see Khales Joumah, “Whose Side Are They On? Iraq’s Arab Tribes Decide Between Kurdish and Extremists,” NIQASH, April 16, 2015, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/politics/3637/Whose-Side-Are-They-On-Iraq’s-Arab-Tribes-Decide-Between-Kurdish-and-Extremists.htm.

3 The other two local council members are Kurdish and from the Arab Juhaysh tribe.

4 According to elders, the Shammar tribe moved from Saudi Arabia to Iraq’s northern border region (including across the border, in today’s Syria) in the 18th century because it resisted the reform movement of Mohammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab; some even became Shi’a. The older Iraqi tribes (“deera”) often provoke the Shammar by calling them Gulf Arabs.

5 Nawzat Shamedin, “Ninewa Tribes and the ‘Caliphate State´: Interest Networks and Violence Paved the Road of State-building and Continuity,” Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism, 2015, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.nirij.org/?p=1234.

6 Ibid.

7 Richard Spencer, “ISIL Jihadists Driven out of Rabia after Two-Day Siege,” Telegraph, October 2, 2014, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/islamic-state/11137455/Isil-jihadists-driven-out-of-Rabia-after-two-day-siege.html.

8 See also, Isabel Coles and Jonny Hogg, “Kurds Seize Iraq/Syria Border Post; Sunni Tribe Joins Fight against Islamic State,” Reuters, October 1, 2014, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-idUSKCN0HO12G20141001.

9 “Kurdish Presidency Says Rojava Peshmerga More Legitimate than YBS,” Rudaw Online, March 3, 2017, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/ad773996-3587 – 4281-ba85-805f2d69cd83/UPDATE – Clashes-halt-between-Rojava-Peshmerga – PKK-affiliate-in-Sinjar.

10 “‘Rojava’…Kurds Who Are Prohibited from Fighting the Assad Regime,” Al-Arabi al-Jadeed, September 13, 2015.

11 The original Zeravanis are Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) units that surrendered to the KDP-Peshmerga. Until 2014, the Zeravani received their salaries from the KRG’s Ministry of Interior, but they have since been brought under the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs for training, weapons, etc. The Zeravani are led by Aziz al-Waysi and only present in KDP-controlled areas.

12 “Ministry of Peshmerga Graduated Thousand Arab Fighters in Khanas Camp in Mosul,” ARA News, February 2, 2017.

13 Isabel Coles, “In Remote Corner of Iraq, an Unlikely Alliance Forms against Islamic State,” Reuters, May 11, 2016, accessed July 1, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-sinjar-idUSKCN0Y20TC.

14 Sheikh Abdallah al-Yawar, an important figure during the U.S.-led “Awakening” or sahwa, has helped with recruitment, but takes no formal role in the Jazeera Brigade.

15 The local police is relatively small (200 members) as result of duplications in tasks with the Asayish.

16 “Member of Parliament Announces Formation of ‘Ninewa Lions’ Force to Liberate the Western and Central Parts of the Governorate,” Al-Sumaria, May 12, 2016, accessed July 1, 2017.

17 The Sheikh first asked KRI President Masoud Barzani to set up a camp in the KRI before approaching the YPG, the natural ally of the Shammar in Syria, but the President rejected his proposal at the time.

18 “Deputy Reveals the Formation of Force,” Al-Sumaria, May 12, 2016.

19 This limitation is not unique; no tribal force unit has been authorized above 600 fighters. Keeping the forces small was part of the overall design of the program to more easily control forces, those working with the TMF program stated.

20 Members of the Ninewa Lions can spend their leave in Rabi’a but the force is not permitted to enter.

21 Although this research has benefitted from the facilitation efforts of people associated with al-Tahreer Association, an independent expert has confirmed that Yazidis asked al-Tahreer to mediate, because they trust the organization’s leadership, and the Shammar tribe in general.

22 He added, “if it was up to Iran, Rabi’a might soon become another Jurf al-Sakhr.” Jurf al-Sakhr is a reference to a Sunni-Arab-majority sub-district in Babel governorate, which was allegedly plundered by Shi’a militias that refuse to let its inhabitants return more than two years after announcing its liberation from ISIL.