Iraq After ISIL: Tal Afar City

Shi’a Arab PMF from the south have been the main forces present around this ISIL-held area, but if they retake this mixed Sunni-Shi’a Turkmen city, it may spark sectarian and regional conflict.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

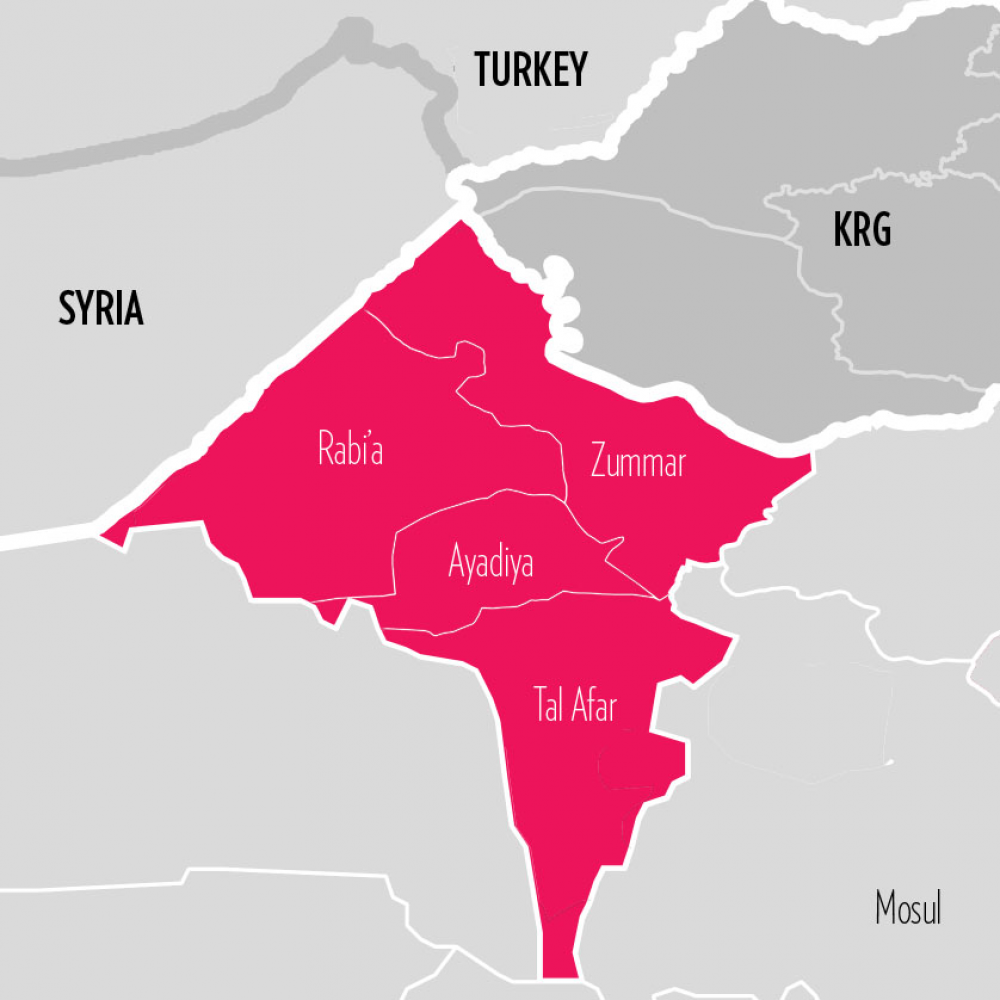

Tal Afar city, located only 63 kilometers west of Mosul, looms large in political and strategic analyses of the dynamics in Ninewa governorate. The city is the administrative center of Ninewa’s Tal Afar district, which also comprises the towns of Rabi’a, Zummar, and Ayyadhiyya. Long an Al-Qaeda stronghold, Tal Afar is the hometown of a substantial number of ISIL fighters and high-level leaders. Tal Afar is also geopolitically significant because of its location near the border with Syria and its split ethnic and political dynamics. When ISIL took control of Tal Afar on June 16, 2014, it solidified control of northwest Iraq and secured its supply lines between northern Iraq and Syria.2 A city split between Sunni and Shi’a Turkmen communities, which have strong ties to other regional powers and sectarian groups in Iraq, Tal Afar is frequently portrayed as a microcosm of the inter-ethnic clashes and regional, proxy power contests that fuel continuing conflict in northern Iraq.3

Tal Afar had not yet been liberated during the field research, and so an in depth community profile was not possible. However, Tal Afar is significant for this research because it is the area in Ninewa governorate where Shi’a PMF have held the largest sway. Following abuses and political backlash when Shi’a PMF took other Sunni cities like Falluja and Tikrit, Shi’a PMF were held at arm’s length in the operations leading up to and surrounding Mosul. However, Shi’a PMF forces have been surrounding Tal Afar since November 2016, and from August 20, 2017, when the operation to retake Tal Afar was launched, they appeared poised to take part in the operation.4 Shi’a PMF’s vantage point in Tal Afar has enabled them to maintain a larger influence in other areas of Ninewa governorate where they have not formally been given a role. The prospect of them taking a large part in the liberation and holding of Tal Afar risks igniting local sectarian rivalries and regional tensions.

Key Facts: Tal Afar City

Population: 200,000

Ethnic Composition: 90% Turkmen (split Sunni/Shi’a)

Date taken by ISIL: June 16, 2014

Date reclaimed: Still under ISIS control

Forces engaged: PMF brigades, Coalition forces

Overall Control: ISIS control as of early July 2017, with PMF on outskirts

LHSFs present: Badr Organization, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq, Kata’ib Hizb Allah

Key Issues:

- Post-liberation sectarian violence sparked by PMF reprisals

- PMF using Tal Afar as a foothold in Ninewa

- Regional tensions / intervention by Turkey

Background and Pre-ISIL Dynamics

The population of Tal Afar before ISIL’s invasion in 2014 was estimated to be 200,000.5 Roughly 90 percent of the city’s population is ethnically Turkmen, whereas only 10 percent is Arab.6 The Turkmen population is divided along sectarian lines between Sunni and Shi’a Muslims; however, the Sunni/Shi’a ratio is hard to establish because the last complete census was held in 1987.7 A 2008 study put the ratio at 75-to-25 (Sunni-Shi’a) during the major U.S. ‘counterinsurgency’ operations in Tel Afar in 2005 and 2006.8 Both a Wilson Center publication and a MERI Policy Report also suggest that the Sunni Turkmen constituted the majority before the invasion by ISIL in 2014.9

Whatever the balance, the sectarian dimensions have been critical drivers of conflict in Tal Afar. Under Saddam Hussein’s rule, Sunni Turkmen were privileged over their Shi’a peers, which manifested in the former’s over-representation in government posts and in the security services.10 After the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the power balance shifted, and Shi’a factions took control of local positions and police forces.11 When Shi’a forces, notably the Badr Organization, infiltrated and took control of local government authorities in Tal Afar, they touched off a tit-for-tat escalation of sectarian tensions and violence.12 Between 2005 and 2006 in particular, there were reports of harsh sectarian policies and harassment of the Sunni population by local Shi’a authorities, including reported instances of torture, extra-judicial killings, and sectarian-motivated property destruction.13 These events sparked sectarian tensions and contributed to the emergence of strong Al-Qaeda factions among the Sunni Turkmen in Tal Afar.14

The strength of Al-Qaeda in Tal Afar made the city a focal point in the US counter-insurgency campaign from 2005 to 2006, which at the time was the second-largest US counter-insurgency operation after Fallujah.15 The stabilization of Tal Afar and rollback of Al-Qaeda’s strength in the area (at least temporarily) was seen as a positive litmus test for the overall US counter-insurgency strategy.16 However, more extreme elements rose to the fore again when Tal Afar fell to ISIL fighters in 2014.

Capture by ISIL

Shortly after taking Mosul, ISIL fighters advanced on Tal Afar, the key access route to their Syrian supply lines. On June 15, 2014, Tal Afar city fell to ISIL forces. Not surprisingly, given Tal Afar’s sectarian-charged past, the fight for Tal Afar was fierce, and different factions in the city joined the fight for or against ISIL along largely sectarian lines. Residents in Tal Afar reported that Shi’a police and troops “rocketed Sunni neighborhoods” before ISIL captured the city. Other analysts, meanwhile, noted that some predominantly Sunni neighborhoods rose up against the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). The Iraqi defense was led by one of the few units that did not flee in the face of ISIL advances, under the command of a Shi’a general. Amnesty International later alleged that retreating ISF units executed Sunni detainees before they left Tal Afar.

When ISIL fighters moved into the city, they destroyed several Shi’a mosques and persecuted and expelled Shi’a Turkmen. With the group in control, some reports suggested that almost all Shi’a Turkmen – an estimated 80,000 – 100,000 people – fled or were forced out of Tal Afar and surrounding areas. Many of those who fled were displaced first into neighboring areas west and north of Tal Afar (e.g., Sinjar and Rabi’a); however, according to interviews and news reports, they also fled into Syria and then further north as ISIL spread. Other IDP tracking reports have documented the displacement of tens of thousands of Shi’a Turkmen from Tal Afar and surrounding areas into other Shi’a‑majority governorates in central and eastern Iraq.

Although the Shi’a Turkmen expulsion was the largest, significant portions of the city’s Sunni Turkmen and Arab populations also fled. There are no reliable numbers of how many of these groups fled. However, by one estimate, only 50,000 of the 200,000 estimated population – and predominantly Sunni Turkmen residents – remained in Tal Afar after ISIL’s take-over.

PMF Activities in Tal Afar

More than any other part of Ninewa, Tal Afar is the area where the PMF have played their most significant role. The city was one of the last ISIL holdouts in Ninewa and was still under the group’s control at the time of research, from February through July 2017. However, in October 2016, the Shi’a PMF, including the Badr Organization, the League of the Righteous (Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq), and the Hezbollah Brigades, had begun gaining territory in Tal Afar’s outskirts, which they could then use as a foothold to counter-attack around the city. On November 16, 2016, the PMF seized Tal Afar airport29 and on March 1, 2017, they took control of the highway leading from Mosul to Tal Afar.30

With other Coalition forces focused on the fight in Mosul, the PMF have been the most active anti-ISIL force engaged in these advances on Tal Afar31 (a notable exception is that four units of Coalition-trained tribal Hashd, some 900 fighters, have been active in the Tal Afar area since the end of February, according to Coalition tracking reports). The Badr Organization appeared to be in the lead in these initial operations, with estimates of the total PMF fighters involved (including from PMF groups other than Badr) ranging from 7,000 to 15,000 militia fighters.32 The PMF have openly stated that they have received support from Iran for Tal Afar operations.33 Although their primary engagement has been militarily, some local aid groups interviewed said that Shi’a PMF groups around Tal Afar had facilitated access for humanitarian groups in the area, and even provided some aid to civilians themselves.

Most of the fighters engaged in Tal Afar operations as of July 2017 were Shi’a fighters from the south, according to most reports; however, there was some marginal participation from local fighters from Ninewa and very minor engagement of other LHSF groups. According to a League of the Righteous spokesman, 3,000 Shi’a Turkmen who were forced out of Tal Afar by ISIL in 2014 and joined the PMF have also taken part in the operations.34 Coalition tracking of tribal units (primarily Sunni) mobilized under the Tribal Mobilization Force program also suggested that two of these TMF units, with fighters who are local from the Tal Afar area, have also been holding position on the outskirts of Tal Afar, roughly co-located with Shi’a PMF but not operating under their command.35 One of these units is a Sunni unit that was officially in the TMF program, receiving Coalition training and support, but withdrew from the program, reportedly due to harassment from Shi’a PMF (although this was not possible to confirm). The other unit is a Shi’a unit, but has reportedly chosen not to affiliate or come under the command of larger, southern Shi’a PMF there.

The PMF advances and hold on areas around Tal Afar were important not only for future operations in Tal Afar, but for other surrounding area. As discussed in the Qayyara and Mosul research summaries, the PMF’s bases around Tal Afar allowed them to remain engaged, if unofficially and sporadically, in other areas of Ninewa. The distance between these areas is quite small, and PMF fighters appear to provide unofficial, ad hoc support in other areas (for example, manning checkpoints with Iraqi forces and other supporting security roles on days where they are short of manpower). The PMF’s close proximity and presence in the area also contributed to their continued efforts to develop local Hashd forces under their direction, including the Hashd Mosul.36 In essence, although the PMF have formally been kept out of most Ninewa operations, Tal Afar has given PMF a physical presence in a strategic location and a way to stay engaged in the governorate.

In June 2017, the Coalition forces announced that they would focus on liberating Tal Afar after Mosul before moving on to Hawija, in Kirkuk. At the time, it was not yet clear what role, if any, the PMF fighters or other LHSF would play in the liberation of Tal Afar. Members of the Sunni community, the Iraqi government, and the broader Coalition have long been hesitant to vocally opposed to any significant PMF role in Tal Afar because they feared this would ignite local dynamics and lead to a repeat of the pre-2014 situation that provoked ISIL’s rise.37 The PMF have been kept on the fringes of other operations in Ninewa due to concerns about the volatility that would follow if these largely Shi’a forces were to take a prominent role in Sunni areas of the governorate.

Others have argued that PMF should not be kept on the sidelines in Tal Afar, given their strategic position surrounding the city and the ISF’s heavy losses and fatigue after the prolonged battle for Mosul.38 Others analysts interviewed speculated that even if desired, PMF would not accept being kept out of the Tal Afar fight. PMF fighters have reportedly vowed to liberate the Shi’a Turkmen, and Tal Afar is a potential strategic launching point for the PMF to push further into Syria and cement a supply line that stretches, through Iraq, from Iran to the Syrian border.39

On August 20, 2017, Iraqi forces, supported by Shi’a PMF began their assault on Tal Afar. Although Reuters reported that the Iraqi army, Federal Police, and Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS), would lead the assault, which has been the trend throughout Ninewa operations, they also reported that Shi’a PMF would take part.40 Meanwhile an Iraqi news outlet cited a PMF statement that they would deploy 20,000 fighters in the battle for Tal Afar.41

Regional Tensions and Future Flashpoints

The battle for Tal Afar has been a focal point of attention not only because it was one of the last remaining cities under ISIL control, but also because of fears of sectarian fighting and cycles of retaliation should PMF fighters take part in the city’s liberation, which now appears likely to happen. PMF fighters have vowed to punish the Sunni Turkmen of Tal Afar, and a July 2017 MERI policy report found that the Shi’a and Sunni communities in Tal Afar both feared the PMF would take revenge during and after the expulsion of ISIL.42 However, the views were split: according to MERI’s findings, each community had different views on where this violence could originate from. Most Sunni community members feared that Shi’a PMF fighters from the south of Iraq would act carelessly in liberating Tal Afar and engage in acts of retaliation; Shi’a community leaders, in contrast, suggested a preference for PMF forces from outside the Tal Afar area because they would not be prone to lose composure over personal grievances.43 Therefore, Sunnis mostly said they preferred Peshmerga or Iraqi government forces, rather than the Shi’a PMF, to take the lead in retaking Tal Afar. Some Shi’a interviewees suggested that local Sunnis should take part in the operation to definitively renounce ISIL.

Others fear that the issue is not limited to immediate retaliation. A strong PMF presence, with the potential to endure, might affect local political dynamics and reconciliation. In an interview, one KRG official, engaged in northern areas of Ninewa that are part of the Tal Afar district, said he viewed future events in Tal Afar and the role of PMF there as critical for the stability of political dynamics in that part of the Ninewa governorate. He expressed that a Shi’a PMF engagement could ratchet up sectarian tensions and make it more difficult to reach local reconciliation. Another Sunni tribal leader from Mosul framed the PMF intervention in and around Tal Afar as a warning sign for larger political dynamics in Ninewa governorate: “The problem is not just that they entered [the area around Tel Afar]. What if they stay, as they have in Salah ad-Din? Really, we are afraid of what will happen if the PMF stay after the elections.”

The potential for PMF retaliation against the local Sunni population, largely Turkmen, has also stoked regional tensions. Turkey has portrayed itself as a protector of the Turkmens, voicing concerns that the Shi’a PMF might attack Turkmen communities if they seize control of Tal Afar. In order to demonstrate its resolve, Turkey mobilized troops at the Turkish-Iraqi border in November 2016. Tensions seemed to ease after a meeting between Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim and Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi on January 7, 2017. Iraqi National Security Advisor, Falah Fayyad, then stated that the PMF would be allowed to enter Tal Afar, and Turkish forces agreed to withdraw from Bashiqa, north of Mosul, after the end of the Mosul offensive. Nonetheless, considerable potential for escalation remains due to Turkey’s strong desire to ensure that the PKK is kept out of northern Iraq, its fundamental opposition to a PMF involvement in Tal Afar, and some inflammatory statements by Erdogan against the PMF in April 2017.

Another potential flashpoint lies in tensions between the PMF and the KDP Peshmerga, which could increase if the PMF became dominant in Tal Afar. KDP Peshmerga forces control the territories north of Mosul and Tal Afar, and the KDP is concerned about PMF forces, which include fighters hostile to Kurds, gaining ground close to Kurdish territories. The Badr Organization met with Peshmerga forces in Sinjar on November 23, 2016, and agreed to coordinate movements with them in retaking the territories north of Tal Afar. However, the leader of the Badr Organization, Hadi al-Amiri, stressed that Peshmerga forces should not be involved in operations south of Mosul and Tal Afar, referring to them as “Arab areas.”

With all of these tensions brewing close to the surface, the focus is not on whether and how Coalition forces will prevail against the 1500 ISIL fighters left in the city, but what happens next in Tal Afar. Analysts interviewed saw the role of PMF during and after operations in Tal Afar as a fundamental litmus test of Prime Minister al-Abadi’s authority. If ISF yet again dominate the fighting (as they did in Mosul) and are able to restrain PMF activities and tamp down tensions surrounding the PMF in this volatile city, that could boost the Iraqi government’s authority. It could enable the Iraqi government to finally gain the upper hand over the Shi’a PMF, who have been critical in the fight against ISIL since 2014 but have repeatedly challenged the Iraqi government’s authority on its own territory. If PMF participate in the fight in Tal Afar and hold territory surrounding it against the Iraqi government’s wishes, it would be the biggest signal that the Iraqi government cannot control the more than 100,000-strong force it has mobilized, and augurs poorly for post-ISIL stability in Iraq.

References

1 One of the last areas to be liberated, Tal Afar was still controlled by ISIL during the period of field research. As a result, unlike all other field reports for this project, no field research or interviews in Tal Afar were possible. However, in interviews in the surrounding areas dynamics in Tal Afar came up frequently.

2 “Iraq Conflict: Militants ‘Seize’ City of Tal Afar,” BBC News, June 16, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27865759; Ziad al-Sanjary and Ahmed Rasheed, “Advancing Iraq Rebels Seize Northwest Town in Heavy Battle,” Reuters, June 1, 2014, www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-security-idUSKBN0EP0KJ20140615.

3 Ramzy Mardini, Tal Afar: Prospect for Escalation (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2016), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/tal-afar-prospect-for-escalation; AFP, “Iraq’s Tal Afar: Turkmen Town in Heart of anti-IS War,” Al-Monitor, October 31, 2016, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/afp/2016/10/iraq-conflict-talafar.html; Cockburn, “‘ISIS is Full of Killers.”

4 A background description of this project and of how LHSFs are defined can be found in Erica Gaston, Andras Derzsi-Horvath, Christine van den Toorn, and Sarah Mathieu-Comtois, Backgrounder: Literature Review of Local, Regional or Sub-State Defense Forces in Iraq (Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute and American University Iraq Sulaimani Institute of Regional and International Studies, 2017), http://www.gppi.net/publications/peace-security/article/literature-review-local-regional-or-sub-state-defense-forces-in-iraq/.

5 BBC News, “Iraq Conflict”; AFP, “Iraq’s Tal Afar”; Mardini, Tal Afar: Prospect for Escalation; Michael Fitzsimmons, John D. Steinbruner, Michael O’Hanlon, George Quester, Robert Sprinkle, and Peter Wien, Governance, Identity, and Counterinsurgency Strategy (Ann Arbor: ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 2009), 77 – 78.

6 Fitzsimmons et al., Governance, Identity, and Counterinsurgency, 78.

7 Mustafa Habib, Counting Iraqis, Why There may Never be a Census Again (Baghdad: NIQASH, 2013), www.niqash.org/en/articles/politics/3238/.

8 David R. McCone, Wilbur J. Scott, and George R. Mastroianni, The 3rd ACR in Tal’Afar: Challenges and Adaptations (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), 2, https://web.archive.org/web/20100816195952/http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil:80/pdffiles/of-interest‑9.pdf; Mardini, Tal Afar: Prospect for Escalation.

9 Gareth Stansfield, The Looming Problem of Tal Afar (Washington, DC: Wilson Center, 2016), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/the_looming_problem_of_tal_afar.pdf; Dave van Zoonen and Khogir Wirya, Turkmen in Tal Afar, Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict (Erbil: Middle East Research Institute, 2017), www.meri‑k.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Turkmen-in-Tal-Afar-Report.pdf.

10 Stansfield, The Looming Problem of Tal Afar; Fitzsimmons et al., Governance, Identity, and Counterinsurgency, 79.

11 Michael Knights and Matthew Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive (Washington, DC: The Washington Institute, 2016), http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/shiite-militias-are-crashing-the-mosul-offensive.

12 George Packer, “The Lesson of Tal Afar: Is it too Late for the Administration to Correct its Course in Iraq?” The New Yorker, April 10, 2006, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/04/10/the-lesson-of-tal-afar.

13 Geneva International Centre for Justice, Iraq: Tal-Afar, the Next Foreseen Bloodshed (Geneva: Geneva International Centre for Justice, 2016), http://www.gicj.org/un-special-procedures-appeals/iraq/478-the-situation-in-iraq-tel-afar; Stansfield, The Looming Problem of Tal Afar; Knights and Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive.

14 Knights and Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive. Tal Afar’s geography also made it a central crossing point for the influx of foreign fighters from Syria, which also contributed to the growth of al-Qaeda in the city from 2004 onward. McCone, Scott, and Mastroianni, The 3rd ACR in Tal’Afar: Challenges and Adaptations, 5.

15 Jon Finer, “H.R. McMaster is Hailed as the Hero of Iraq’s Tal Afar. Here’s what that Operation Looked Like,” The Washington Post, February 24, 2017, www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2017/02/24/h‑r-mcmaster-is-hailed-for-liberating-iraqs-tal-afar-heres-what-that-looked-like-up-close/.

16 Packer, “The Lesson of Tal Afar.”

17 BBC News, “Iraq Conflict.”

18 Al-Sanjary and Rasheed, “Advancing Iraq Rebels Seize Northwest Town in Heavy Battle,” Reuters, June 15, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-security-idUSKBN0EP0KJ20140615.

19 Knights and Schweitzer argue that as ISIL advanced on Tal Afar, “Sunni neighborhoods of Saad and Qadisiyah rose up against the Iraqi Army.” Knights and Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive.

20 “Tal Afar had been defended by an [sic] unit of Iraq’s security forces commanded by a Shi’ite major general, Abu Walid, whose men were among the few holdouts from the government’s forces in the province around Mosul not to flee the rapid ISIL advance.” Ziad al-Sanjary and Ahmed Rasheed, “Advancing Iraq Rebels Seize Northwest Town in Heavy Battle.”

21 According to a June 2014 Amnesty International report citing surviving detainees and relatives of victims, before withdrawing from Tal Afar, GOI forces killed 50 Sunni detainees without a trial in revenge for ISIL gains. Amnesty International, “Iraq: Testimonies Point to Dozens of Revenge Killings of Sunni Detainees,” Amnesty International News, June 27, 2014, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2014/06/iraq-testimonies-point-dozens-revenge-killings-sunni-detainees/.

22 Knights and Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive.

23 The Centre for Academic Shi’a Studies, Threats to the Shia Turkmen Community of Iraq by ISIS (London: The Centre for Academic Shi’a Studies, 2014), 1, http://www.shiaresearch.com/Doc/ThreatstoShiaTurkmenbyISFINAL.pdf.

24 Knights and Schweitzer provide the example of ISIL conduct in nearby Turkmen villages of Guba and Shireekhan, noting that “the Islamic State ordered 950 families to leave, ransacked Shiite homes, burned agricultural land, and dynamited three Shiite places of worship. […] By June 20, nearly all of Tal Afar’s Shiite population had been killed or fled after door-to-door searches for Shiite residents.” Knights and Schweitzer, Shiite Militias Are Crashing the Mosul Offensive.

25 Several interviewees in the field research surrounding Rabi’a and Zummar subdistricts noted the displacement of significant numbers from Tal Afar into their areas and north of Duhok. Other news media reported displacement into Sinjar and west into Syria. Al-Sanjary and Rasheed, “Advancing Iraq Rebels Seize Northwest Town in Heavy Battle.”

26 A report by REACH based on informant interviews estimates that 30,000 Shiite Turkmen and Shabak households from Tal Afar and the Ninewa plains arrived in Shiite-majority governorates. REACH, Iraq IDP Crisis Overview, 3 – 18 August 2014 (Geneva: REACH, 2016), reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-idp-crisis-overview‑3 – 18-august-2014.

27 The difficulty of obtaining precise displacement estimates is made more difficult by the lack of firm, pre-ISIL census data on the exact population figures and ethnic breakdown. For example, one official quoted by Reuters noted that “Shi’ite families have fled to the west, and Sunni families have fled to the east,” but beyond such vague statements, precise population numbers and movements are difficult to verify. Al-Sanjary and Rasheed, “Advancing Iraq Rebels Seize Northwest Town in Heavy Battle.”

28 Geneva International Centre for Justice, Iraq: Tal-Afar, the Next Foreseen Bloodshed; Rudaw, “Many from Tal Afar Flee to Safety of Peshmerga after Hashd-ISIS Clashes,” Rudaw, June 6, 2017, http://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/060620171.

29 Shelly Kittleson, “Shiite Forces Advance on Tal Afar in Mosul Operation,” Al-Monitor, December 1, 2016, http://al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/12/tal-afar-iraq-mosul-turkey-pmu-syria.html.

30 “Mosul Battle: Iraqi Forces Cut IS Escape Route to Tal Afar,” BBC News, March 1, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-39126647.

31 Shelly Kittleson, “Shiite Forces Advance on Tal Afar in Mosul Operation.”

32 Bill Roggio and Amir Toumaj, “Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces Close in on Tal Afar,” FDD’s Long War Journal, November 23, 2016, www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2016/11/iraqi-popular-mobilization-forces-close-in-on-tal-afar.php; Cockburn, “‘ISIS is Full of Killers”; Geneva International Centre for Justice, Iraq: Tal-Afar, The Next Foreseen Bloodshed.

33 Roggio and Toumaj, “Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces Close in on Tal Afar.”

34 Ibid.

35 This is based on tracking conducted by the US Diplomatic Mission to Iraq, and shared with the members of the research study.

36 Rise Foundation, Post-ISIS Mosul Context Analysis (Erbil: Rise Foundation, 2017), 18, https://rise-foundation.org/selected-reports/.

37 Reportedly, in October 2016 Prime Minister al-Abadi invited Tal Afar Shia and Sunni tribal leaders to Baghdad to discuss the city’s liberation. However, Sunni leaders did not attend since they anticipated PMF involvement was inevitable and wanted to avoid the impression of approving PMF participation with regard to their constituencies. Van Zoonen and Wirya, Turkmen in Tal Afar, Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict.

38 This was an emerging pattern in July 2017 in the Tal Afar area, with ISF forces capturing villages east of the city as they moved west of Mosul.

39 Ahmad Majidyar, “Iraqi Paramilitary Forces Say Will Participate in Tal Afar Operation despite Sunni Concerns,” Middle East Institute, June 23, 2017, www.mideasti.org/content/io/iraqi-paramilitary-forces-say-will-participate-tal-afar-operation-despite-concerns; Tom Westcott, “On the Road to Mosul, Liberation Comes Tinged with Sectarian Suspicion,” IRIN News, November 29, 2016, http://www.irinnews.org/fr/node/259175; Chris Tomson, “Iraqi Army Captures Key Mountain Overlooking Tal Afar City – Mosul Battlefield Update,” Almasdar News, March 6, 2017, https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/iraqi-army-captures-key-mountain-overlooking-tal-afar-city-mosul-battlefield-update/; Muhannad Al-Ghazi, “Iraqi Forces Prepare to Retake Western Mosul,” Al-Monitor, February 10, 2017, http://al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/02/mosul-right-bank-islamic-state-iraq.html; Athanasios Manis and Tomáš Kaválek, The Catch-22 in Ninevah: The Regional Security Complex Dynamics between Turkey and Iran (Erbil: Middle East Research Institute, 2016), http://www.meri‑k.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Policy_note_vol3.No4_.pdf; Roggio and Toumaj, “Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces Close in on Tal Afar.”

40 Pollack, Iraqi Kurdistan: Mosul and beyond; Manis and Kaválek, The Catch-22 in Ninevah.

41 Tim Arango, “Iran Dominates in Iraq after U.S. ‘Handed the Country Over’,” The New York Times, July 1, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/07/15/world/middleeast/iran-iraq-iranian-power.html.

42 Pollack, Iraqi Kurdistan: Mosul and beyond.

43 Van Zoonen and Wirya, Turkmen in Tal Afar, Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict.

44 Roggio and Toumaj, Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces Close in on Tal Afar; Middle East Institute, “Iran-Led Militia Forces Planning to Seize Iraq’s Tal Afar.”

45 Cockburn, “ISIS is Full of Killers.”

46 Sevil Erkuş, “Turkish Troops to Retreat at End of Mosul Offensive but Camp Should be Iraqi: Ambassador,” Hurriyet Daily News, January 11, 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-troops-to-retreat-at-end-of-mosul-offensive-but-camp-should-be-iraqi-ambassador-.aspx?pageID=238&nID=108393&NewsCatID=352; Ahmed Rasheed and John Davison, “Iraq Says Deal Reached over Bashiqa, Turkey Says Issue will be Solved,” Reuters, January 7, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-turkey-abadi-idUSKBN14R0D4.

47 Roggio and Toumaj, Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces Close in on Tal Afar.

48 On April 4, 2017, Erdogan stated he might consider intervening in Tal Afar in an interview with Anadolu. On April 19, 2017, Erdogan further heightened tensions by describing the PMF as a terrorist entity in an Al-Jazeera interview. Hamdi Malik, “Ankara not Backing Down from Iraq Intervention,” Al-Monitor, April 19, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/04/iraq-turkey-iran-sinjar-pkk-kurdistan.html.

49 Manis and Kaválek, The Catch-22 in Ninevah.

50 Shelly Kittleson, “Shiite Forces Advance on Tal Afar in Mosul Operation.”

51 Ibid.