At the Tip of the Spear: Armed Groups’ Impact on Displacement and Return in Post-ISIL Iraq

This report is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings and research summaries about other field research sites.

Nearly six million people in Iraq have been displaced since ISIL launched its large-scale offensive and took over large swaths of the country in mid-2014. An estimated 1.8 million were still displaced as of January 2019.1 There are many factors that drove this displacement or have deterred many internally displaced persons (IDPs) from returning: from security threats by ISIL or other actors, to a lack of water, electricity and food, to limited economic opportunities, and a lack of access to schools or other basic services.2 However, one key contributing factor has been the presence of a range of local and sub-state forces that mobilized against ISIL and still retain significant control in many areas. In some places, these local or sub-state security forces helped improve security, enabling displaced populations to return. However, many of these forces were also implicated in the extrajudicial killing, detention, or abuse of civilians, as well as property destruction and looting – abuses that further drove displacement or deterred return. Local and sub-state forces were also directly involved in blocking some IDPs’ return, and in forcibly displacing families or communities from their homes.

Public reporting on these issues so far suggests that the mass mobilization of irregular, undisciplined, and often partisan or sectarian forces can pose significant risks for civilians and hamper stabilization efforts. However, GPPi’s research found a more complex picture. The behavior of local and sub-state forces was certainly a driver for negative displacement and return trends; however, the violations or abuse committed by these sub-state forces were often at the behest of other government or community actors, or partly attributable to larger security and control dynamics in Iraq. Problematic actions by these quasi-state or sub-state forces were an extension of national or local political fault lines. This web essay analyzes these dynamics by extracting the findings on displacement and return from a larger 2017 – 2018 study on the impact of local and sub-state forces in northern and central Iraq. It provides a sample of some the empirical data indicating how local and sub-state forces affected displacement and return trends, and offers a number of lessons about the broader consequences of mobilizing and deputizing sub-state or non-state actors.

Background: What Are LHSFs and Why Are They Important to Understanding Displacement and Return?

In 2017, GPPi conducted a year-long research project with the goal of documenting and assessing the role and impact of local, sub-state and hybrid security forces (LHSFs, as this project refers to them) in 11 case study areas in the Iraqi governorates of Ninewa, Salah ad-Din and Kirkuk. This included the impact in terms of human rights and protection concerns. When GPPi initiated this research project, existing reporting and documentation by aid groups and human rights organizations suggested links between LHSFs’ control of an area and significant displacement as well as a lack of return of IDPs. Many of these forces were hastily organized militias with weak command and control structures and criminal elements within their ranks. Others were mobilized along ethnic, sectarian or political lines, and were reported to be using their positions of control to harass the most vulnerable members of opposing groups, including by detaining or abusing IDPs, encouraging further displacement of rival groups, or blocking families or individuals from returning to their homes. Many IDPs reported that fear of these security actors was a major deterrent to their return.

To better understand these trends and the connection between LHSFs’ presence and local displacement and return patterns, GPPi researchers conducted interviews with local officials, civilians, humanitarian workers, and other informal security and governance actors in each of the 11 case study areas.3 In addition, GPPi consulted with other humanitarian and research organizations involved in monitoring displacement and return to cross-check some of the findings and better understand how the trends in the 11 research areas reflected broader displacement and return patterns in post-ISIL Iraq.

Although these patterns varied significantly from one area to another, several clear and overarching trends related to the impact of LHSFs emerged. The subsequent sections will draw out five of the most important and cross-cutting dynamics:

- Disputed Territories issues (KRG forces): In areas controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), there was a strong pattern of large-scale property destruction and blocked returns of Sunni Arab communities. KRG officials tended to explain such actions as necessary responses to security threats but they appeared to also be partly driven by the competition for areas known as the “Disputed Territories,” a long-standing political issue in Iraq.

- Sectarian abuses and strategic control (larger Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) forces): Some of the most flagrant and well-documented abuses against civilians – including regular and mass detentions, abuses against returning IDPs at checkpoints, forced displacement of groups, and looting and destruction of the property of those who had fled – were attributed to the leading Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). Such abuses appeared in line with these forces’ history of sectarian strife, but were also more acute in areas where the PMF forces in question sought more extended territorial control and, in some cases, appeared connected to larger political agendas. In some cases, they also overlapped with more systemic issues within IDP management.

- Local and minority forces: Reports of abuse by larger PMF groups were also more severe in cases where these groups partnered with and mobilized local forces, who used their security authority and remit to disadvantage or discriminate against rival ethnicities, tribes, or political groups. Many of the most extreme examples of displacement and non-return were connected to local rivalries between minority forces in an area.

- “ISIL families”: A common thread across all areas and actors – both LHSFs and state actors – was the discrimination, abuse, forced displacement, and blocked return of those with a presumed affiliation with ISIL. This included the wives, children and extended relatives of ISIL members, who were often collectively referred to as “ISIL families.” Many different LHSFs contributed to the wrongful displacement and blocked return of ISIL families, but often in partnership with or at the behest of a wider circle of government and community actors.

- System effects (rule of law and IDP management issues): LHSFs also indirectly contributed to negative migration trends. The mass mobilization and deputization (in the security realm) of such a multiplicity of actors weakened the rule of law and contributed to perceptions of insecurity, which deterred many IDPs from returning. The multitude of actors and unclear mandates also complicated the administration of migration and return issues, while the poor reputation of many LHSFs complicated humanitarian actors’ ability to manage return.

These five dynamics are not ranked in terms of the gravity or seriousness of the displacement and return effects. Given the significant variance among groups and localities, and the differing nature of the violations or displacement effects, attempting to rank them would amount to comparing apples and oranges. Instead, these five dynamics are presented in this order to better illustrate the clustering of these dynamics by geographic area and by the responsible LHSF, and to be able to situate these LHSF-specific trends within larger communal or system effects in the concluding two sections.

As the list of key issues already suggests, LHSF misbehavior or abuses were a significant contributor to displacement and an obstacle to return. This was the most common way in which LHSF behavior produced negative displacement and return effects. Thus, although the overall focus of this web essay is displacement and return, each section also considers allegations of LHSF abuses, and how the presence of abusive LHSFs affected the overall protection environment. This in turn influenced displaced communities’ willingness to return or to remain displaced.

The discussion of these major trends or themes will primarily draw on the initial field research findings. However, since the initial field research was limited to the period of January through August 2017 and return and displacement trends continued to evolve from that point, some sections will note additional research findings from follow-up interviews or other organizations’ analyses. Given the summary nature of this web essay, each section can only provide a sample of the findings related to each trend, but will provide additional links to other parts of this project or to other relevant research.

Historical Grievances, Current Ambitions: Peshmerga and KRG Security Forces, and Disputed Territories Issues

As ISIL took over large swaths of territory in Ninewa and Salah ad-Din in June 2014, the forces of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), commonly known as the Peshmerga, stepped in to hold the line along their borders. They also fought alongside Iraqi and Coalition forces in later liberation operations. In 2014, the KRG Peshmerga were the only sub-state force that was constitutionally authorized and they are closer to a state force than the other LHSFs mentioned in this study, with better command and control and better organization. (For more on different KRG security forces and Peshmerga divisions, see the main project report at p. 24 – 25). However, while more organized, the Peshmerga and other KRG security forces (including the Asayish, the KRG internal security forces) present unique challenges to unitary state control in Iraq, and these broader political tensions spilled over into concerning displacement and return effects.

For the last several decades, the KRG has maintained a degree of quasi-sovereignty and independence from the rest of Iraq, and KRG leaders have frequently called for full independence. This has provoked tensions with the central government in Baghdad, and these tensions have frequently flared over a strip of land along the border of KRG- and Baghdad-controlled areas, known collectively as the Disputed Territories, which both the KRG and the Baghdad government claim.4 ISIL occupied or threatened to occupy virtually all of the Disputed Territories. As these areas were defended or recaptured from ISIL, the KRG was able to assume authority for areas previously under Baghdad’s control, including the long-coveted, multi-ethnic and oil-rich governorate of Kirkuk. From mid-2014 until August 2017, KRG-controlled territory expanded by 40 percent. While the immediate objective may have been to defeat ISIL, the resulting change in control appeared to advance long-held Kurdish dreams of an independent state containing much of these Disputed Territories. When asked about the Iraqi army’s inability to secure Kirkuk, KRG President Masoud Barzani was very candid: “I saw it in an opportunistic way.” However, these gains were reversed in October 2017 following a Kurdish referendum for independence, which the Iraqi government responded to by sanctioning the KRG and forcibly reassuming control of all Disputed Territories.

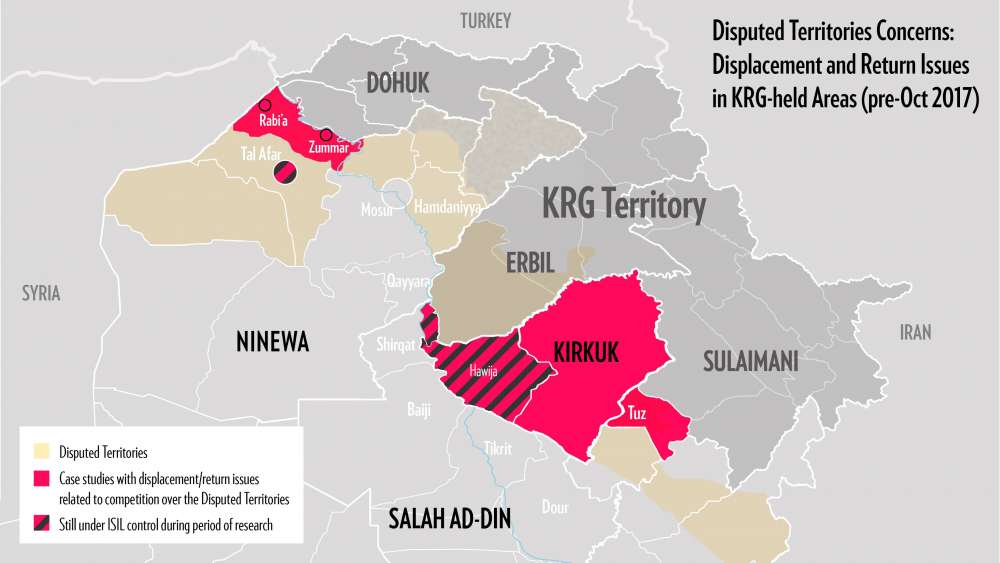

Several of these areas temporarily held by the KRG were part of GPPi’s case studies: Kirkuk governorate, the northern half of Tuz Khurmatu district (hereinafter “Tuz”) in Salah ad-Din, parts of the Ninewa Plains, and Ninewa’s Zummar district, as well as the border town of Rabi’a, which is not formally part of the Disputed Territories but is adjacent to it. The map below illustrates the case studies in GPPi’s initial research (which was carried out up until August 2017) that involved these Disputed Territories issues. It also offers a rough illustration of the area that is generally considered to be the Disputed Territories (the yellow band and the areas included in GPPi’s case studies, minus Rabi’a). It is important to note that there is no clear constitutional definition of the Disputed Territories, and the boundaries of this territory are estimated differently by different organizations and sources (for other descriptions and illustrations of this territory see USIP’s 2011 Disputed Territories study at p. 40, Clingendael Institute’s 2018 study on KRG issues at p. 10, ICG’s 2018 report on mediating the Disputed Territories issues, and HRW’s 2016 report on abuses connected to Disputed Territories). This map offers only a rough approximation of commonly understood delineations of this territory.

Before the Iraqi state resumed control in October 2017, many of the KRG policies in these areas – including how IDP issues were dealt with – appeared motivated by a desire to reinforce and maintain Kurdish control of these areas beyond the immediate ISIL threat. Across all of these areas there were strong patterns of intimidation and forced displacement of predominantly Sunni Arab communities, and some severe examples of blocked returns. In Kirkuk district, Kurdish officials razed and emptied a number of Arab villages and informal settlements in and around Kirkuk city.5 Human Rights Watch alleged that Kurdish security forces were responsible for the partial or complete destruction of 60 Sunni Arab villages along the Kurdish security barrier in 2016. Amnesty International reported that return to these villages was restricted and that, by late 2017, many residents remained in IDP camps. Local and Kurdish authorities also reportedly expelled Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen IDPs who originated from other governorates: Human Rights Watch reported that 12,000 people were expelled in September 2016 alone.

Kurdish security forces said these measures were necessary given the risk of ISIL sleeper cells, and much of the property destruction and restrictions took place concurrently with several security incidents and major attacks (e.g., on KRG forces in Kirkuk city or in Taza). However, these measures had the effect of shifting the proportion of the Kurdish versus Arab populations in this critical part of the Disputed Territories, and many of GPPi’s interviewees suspected that they were connected to broader Kurdish ambitious for future control. A full discussion of the Disputed Territories issues have been better covered elsewhere; however, a brief background on why the demographics matter is important in understanding displacement trends. For the last several decades, both the KRG and Baghdad have sought to buttress their claims to the Disputed Territories (and particularly to Kirkuk) by arguing that the population in these areas is ethnically aligned with their side (Kurdish or Arab, respectively), or that Kurds or Arabs alternately have a greater legal or historical claim to each area. At times, those in control have attempted to reinforce these arguments by changing the facts on the ground. In the 1980s, Saddam Hussein’s regime attempted to forcibly “Arabize” Kirkuk by moving Arab families there while imposing restrictions on Kurdish ownership or otherwise limiting Kurds’ rights in order to push the Kurdish population to move away (p. 46 – 48).

As Kurdish influence in Iraq grew post-2003 under US occupation, the pendulum swung the other way and Kurds pursued a policy of “normalization” in Kirkuk that was, according to the ICG (p. 11), “essentially a methodical reversal of Arabization.” In addition to buttressing a normative claim to ownership, demographic shifts to one side or the other could also shift political power through future voting. Article 140 of the 2005 Iraqi constitution promises a referendum to determine the status of Kirkuk and other Disputed Territories based on the “will of their populations” (for more on Art. 140, see the ICG’s report, p. 11 – 16). In addition to potentially swaying control in local elections, the demographics of the voting population could also favor one side or another and shift these areas to either Kurdish or Iraqi government control should that Article 140 referendum ever be called.

Given this context, displacement and return patterns that tilt the population toward one side or another can be taken with a grain of salt. Even if attributed publicly to security concerns, the forced displacement and blocked return of Sunni Arab communities effectively reinforced bigger Kurdish objectives with regard to the Disputed Territories by reducing the Sunni Arab population in Kirkuk. KRG officials’ public and private statements made it seem as if this effect was not coincidental. Directly addressing KRG policies that blocked the return of certain Arab IDP communities to Kirkuk, KRG President Masoud Barzani told Human Rights Watch (p. 3) in July 2016 that the KRG would not allow Sunni Arabs to return to villages that had been “Arabized” by former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. One foreign diplomat interviewed for this research characterized the displacement and return policies in the KRG-occupied Disputed Territories as part of a broader plan for “ethnic gerrymandering” with an eye on future elections and referendum votes.

Similar patterns emerged in other liberated areas under KRG control, albeit to a lesser degree. Most residents in the northern half of Tuz interviewed for this research viewed Kurdish protection positively, and there were fewer examples of property destruction or intimidation with mass displacement effects. However, several Arab villages in Tuz’s central subdistrict were allegedly razed during or after ISIL’s ouster, while others close to Sadiq Airbase — Hulaywa 1 and 2, and Khashamina — were declared part of a newly designated “militarized zone,” rendering return impossible. Kurdish forces denied residents of three Kurdish-controlled Arab villages in Suleiman Bek subdistrict permission to return.

In Zummar and Rabi’a, the overall rate of return was relatively high and displaced communities returned relatively quickly after ISIL was ousted. However, a number of Sunni Arab communities or villages that were designated as affiliated with ISIL were destroyed, and those who did not return in both areas argued that it was because of such property destruction and fear of further repercussions. Four villages northeast of Rabi’a town — Mahmoudiyya, Qahira, Saudiyya, and Sfaya — were destroyed, reportedly by Kurdish forces, and only a few individuals or families from these populations were permitted to return. In Zummar, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented that two Arab-majority villages, Barzan and Shikhan, were reduced to ashes and rubble, and that the houses and shops of Arabs were torched in mixed-community Zummar town and Bardiyya village. Amnesty International alleged that local Kurds and/or Peshmerga burnt and blew up the houses of Arabs in revenge for their support for ISIL. Key informants confirmed that Kurdish security forces destroyed Arab property in four towns in Zummar subdistrict in retaliation for their alleged support for ISIL. Kurdish security officials interviewed during the research rejected these claims, stating that the destruction was a result of Coalition air strikes as well as a fallout of the extraordinary amount (222 tons) of explosives that ISIL left behind in these villages. This high level of property destruction, combined with the high scrutiny with which requests for return from members of these communities were treated, had a significant effect on return. A survey conducted by IOM among former Zummar residents who had not yet returned found that 40 percent of them feared reprisals if they were to return — by far the highest number of such responses in the IOM study, which covered eight areas. Beyond the deterrent effect of property destruction, Kurdish forces also actively limited the return of Arab citizens to Zummar, only allowing return after strong criticism by international observers. A year after ISIL’s ouster, Amnesty International reported that Arab residents were still barred from entry even though displaced Kurds had returned to their homes just weeks after.

Across Kirkuk, Tuz, Zummar, and Rabi’a, incidents of property destruction, forced displacement and blocked return — even those at the village or neighborhood level — were justified under the pretext of preventing ISIL sleeper cells or otherwise dismissed as collateral damage. However, human rights organizations argued that the measures went beyond basic security protections. They also appeared to play into a much larger political contest preceding the security challenges and conflict with ISIL. In many of these areas, the effect was a de facto reversal of the “Arabization” of the Disputed Territories of the 1980s and a change in demographics in favor of the Kurdish population — a dynamic that Kurdish officials openly endorsed.6 Such important demographic shifts were significant at a time when a Kurdish independence referendum was on the horizon, and control of the Disputed Territories appeared to be a more open question than it had been in decades. These trends illustrate how population displacement and return was used as a strategy for control. Such patterns frequently overlapped with parallel strategies of mobilizing or coopting LHSFs in order to control a territory, and LHSFs were often at the center of these forced displacement or blocked return maneuvers, albeit at the behest of larger political stakeholders.

Power to Control, Power to Exclude: Displacement and Blocked Return by Leading PMF Forces

Some of the most prevalent and serious allegations of abuses against IDPs and of instances of blocked return concerned the Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) (also known as “PMU” or Hashd), which is the general name for about 50 different forces that mobilized in response to the ISIL threat in mid-2014. Although GPPi’s research found ample evidence to support these allegations of abusive behavior, and of the subsequent negative displacement and return effects, there were important distinctions in terms of the motivation or nature of the violence. Some of the acts of violence against IDPs appeared to be perpetrated by individual forces or units within the PMF (in a sense ad hoc abuses by individual militiamen), while others appeared to have deeper political or sectarian motivations. In addition, while there were more frequent allegations of abuse against some of the stronger, leading PMF organizations — who tend to stem from southern Iraq — GPPi’s field research found that in some cases it was smaller forces mobilized from liberated communities in north and central Iraq who were to blame. Another important distinction is that, while PMF forces were involved in acts of forced displacement or blocked return, these violations were frequently carried out with the tacit or overt approval of other government officials or communities. To better analyze these different motivations and effects, this section will first focus on the negative displacement and return trends attributable to a group of leading, national PMF, while the subsequent two sections will discuss displacement effects surrounding locally mobilized PMF forces and some of the broader issues of community or governmental complicity.

Before getting into the specific displacement issues, it is important to identify the specific groups at issue for this section’s discussion. Though initially more of an ad hoc call to arms, the PMF cohered over time into a formalized institution and was legalized as a sub-state force in November 2016 (see here and here for more information). Several of the groups within the PMF existed long before the ISIL crisis: the Badr Organization formed in the 1980s, while groups like Asa’ib Ahl al Haqq (AAH) or the Peace Brigades (not the focus of this section) formed after 2003 in response to the US intervention (see this backgrounder for more on PMF groups’ history and characteristics). These long-standing forces tended to be larger than newer PMF units, well organized and equipped, and more militarily capable. When the Iraqi army collapsed in mid-2014, these pre-existing PMF forces were among the first to respond and to halt the advance of ISIL. They played a significant role in the liberation of many areas early in the campaign against ISIL, and also tended to play a more prominent role in “holding” areas after ISIL was ousted. They have maintained substantial influence and presence in areas across northern and central Iraq well after their liberation, and continued to do so up to the time of writing.

However, while strongest on the battlefield, many of these larger, pre-existing PMF forces entered the anti-ISIL fight with a reputation for abusive behavior and a distinct political agenda. A contingent of these stronger, pre-existing militias is strongly associated with Iran and a sectarian, pro-Shi’a agenda. This includes the Badr Organization, AAH, the Hezbollah Brigades, and the Khorasani Brigades. A 2016 Carnegie Endowment report characterized this subset of PMF groups as the ‘Pro-Khameini faction’ (p. 13 – 14), distinguishing them even from other long-standing, Shi’a PMF groups (such as Moqtada al-Sadr’s Peace Brigades). This is partly due to the many years of substantial support and training these groups received from Iran as well as their association with the Iranian interpretation of political Islam (wilayat al-faqih). However, these predominantly southern Shi’a groups also have a more sectarian, pro-Shi’a reputation because of their alignment with certain political factions in Iraq and past behavior. Prior to 2014, groups like the Badr Organization were a central part of former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki’s strategy of sectarian control, and participated (alongside government forces) in sectarian abuses against Sunni populations in places like Tal Afar, Mosul and other Sunni areas.

This particular subset of the PMF stood out in GPPi’s research areas as having the most negative impact on civilian protection, displacement and return. Whether because of their sectarian tendencies and reputation or simply as a result of their greater capacity to inflict harm, as these Shi’a PMF groups entered Sunni-majority areas during the liberation or stabilization campaigns, allegations of abuse, discrimination against Sunni communities, and extreme violence followed them. This included frequent instances of mistreatment of IDPs, forced displacement and blocked returns. The biggest share of the allegations concerned AAH and the Hezbollah Brigades, although there were also reports of abuse involving the Badr Organization, the Khorasani Brigades, or other Shi’a PMF units. The remainder of this section will summarize the effects of the abuses committed by these organizations, which will be generally referred to as PMF. The map below highlights some of the case study areas where Shi’a PMF forces had a strong influence among GPPi case study areas.

Initial Liberation and Aftermath

Many of the alleged abuses by PMF fighters took place during the initial phase of liberation of the respective area or in the immediate aftermath. There is extensive documentation of abuses committed by PMF forces as they helped liberate Falluja and parts of Salah ad-Din in 2015 and 2016, including extrajudicial killings and detention, torture, large-scale property destruction, and looting. Such abuses prompted the displacement of Sunni communities in the affected areas and sparked fear among Sunni populations in other ISIL-occupied areas as the campaign advanced. Beginning with the air operations in Tikrit and then more seriously during the Mosul campaign,7 there were efforts to limit such abuses by keeping PMF fighters behind the frontlines and limiting their formal areas of operation. Nonetheless, although the PMF were pulled back from taking part in the initial fighting to oust ISIL in many areas, they immediately followed behind the frontlines and took control of some of the liberated areas. As they did so, PMF fighters engaged in looting, property destruction, extrajudicial detentions, and other severe abuses against Sunni tribal communities, which sparked further displacement or delayed communities’ return. 8 Examples of such behavior abounded in the GPPi case studies in Baiji, Dour, Tikrit, and Shirqat, and have also been reported by other organizations investigating Shi’a PMF operations in other areas (e.g., in Anbar, Kirkuk, and Diyala).

In addition to spurring displacement, some of the abuses in this initial phase were directed against IDPs themselves, perpetrated against those trying to flee the area. For example, during GPPi’s research in Dour, locals reported one incident in which one of the Shi’a PMF groups (locals affiliated with the Hezbollah Brigades) rounded up IDPs who had fled the fighting and detained all the men in the group. More than two years after the incident, the majority of the 300 men detained had not yet been released, and relatives presumed they had been killed or were still held in PMF-run detention facilities in Salah ad-Din, which were still operative at the time of writing. There were similar reports in other governorates outside of GPPi’s research area. For example, UNAMI (p. 19 – 20) reported that the Hezbollah Brigades detained 1500 young men and boys from among IDPs fleeing Saqlawiya near Fallujah in Anbar in June 2016. They beat them at the point of capture and then brought them to informal detention sites where they were held in inhumane and substandard conditions and subjected to further abuse.

These initial abuses also had knock-on effects in other Sunni communities. For example, during GPPi’s research, Tal Afar was still occupied by ISIL, but Shi’a PMF groups were poised to take part in the liberation and control of the area. They also vowed to take revenge on the Sunni population. Sunni IDPs, who at the time were displaced due to ISIL’s occupation of the area, said they were afraid to return post-liberation because of the reputation of Shi’a PMF units and past abuses. The Rise Foundation found that this fear of return persisted even after the liberation of Tal Afar, and resulted in a higher percentage of returns among the Shi’a than Sunni population (Tal Afar’s population has historically been mixed Sunni-Shi’a). The Rise Foundation also noted that “IDPs and local Sunni officials alike said that some Sunni Tel Afar residents are not planning to return anytime soon out of fear of retributory attacks” (p. 40).9

Reporting about how abuses by PMF fighters occurred as well as the behavior or attitudes of the perpetrating forces suggests that retaliation and a lack of effective discipline and control were behind many of the incidents that took place during this initial phase. The individuals GPPi interviewed for its Tikrit case study suggested that the PMF abuses and looting in the areas around Tikrit and Dour were perceived as collective retribution for the so-called “Camp Speicher massacre,” during which ISIL killed several hundred Shi’a recruits in a seemingly sectarian-motivated mass execution. UNAMI’s reporting on the mass detention in Anbar described above found similar retaliatory motives: “When they [some of the 1500 men detained] asked for water, food or air, they were abused by militia members, told that their treatment was ‘revenge for Camp Speicher’, and beaten with shovels, sticks and pipes” (p. 19). However, while a desire for revenge may have motivated the individual forces or units in the immediate instance, an important underlying factor was the lack of control of the PMF as a whole, as well as the absence of strong disciplinary measures. This lack of control was particularly problematic in 2015 and 2016, when the PMF were still a new phenomenon, the Iraqi army was still struggling to rebuild, and the ISIL campaign was at its height.

Lower-Level but Sustained Abuse and Forced Disappearances

The number of reports of abuses by PMF units as well as the negative displacement and return trends they provoked tended to decline after the initial liberation phase, as the respective areas transitioned to Iraqi government control. For example, although there were substantial allegations of abuse, property destruction, extrajudicial detentions, and killings in the districts of Tikrit and Dour in the initial period following their liberation (March – April 2015), by the time of GPPi’s field research (in 2017) Iraqi forces were largely in control. Reports of such violations had declined significantly and the rate of return was relatively high (up to 90 percent).

However, while the reports of arbitrary detentions, abuse or harassment of IDPs (or other civilians) by the PMF declined, they did not entirely disappear. Many of these reports of harassment of IDPs or blocked return that continued well after the initial liberation took place at PMF-controlled checkpoints. An HRW study of forced disappearances covering the period from 2014 to 2017 found that roughly half (34 of 74) of these individuals were taken at checkpoints. In GPPi’s areas of research, for instance, most of the reports of disappearances or arbitrary detention by PMF took place along the main Highway 1 that cuts through Salah ad-Din to Baghdad, where the PMF controlled many of the checkpoints. In extreme cases, individuals were detained for prolonged periods or never allowed to return. Even more instances of abuse and disappearances have been reported for the PMF-controlled Al-Razzaza checkpoint in Anbar governorate (beyond the scope of GPPi’s research). According to Amnesty International (p. 21), members of the Iraqi parliament alleged that some 2200 individuals had been detained at the Al-Razzaza checkpoint, most by the Hezbollah Brigades, and that few had returned to their families.

These issues of forced disappearances and detentions at checkpoints overlap with some of the issues that will be discussed in the subsequent two sections. Arbitrary detentions (not only at checkpoints but also in home raids) were often jointly perpetrated with other actors (government and non-government), and were often connected to broader sentiments of collective punishment against those perceived as affiliated with ISIL. In some cases, they were also the result of systemic issues regarding the management and security of IDPs. These problems will be revisited and discussed in greater detail in the subsequent sections.

Lastly, it is worth considering how the effect of abuses perpetrated during the initial liberation phase and its aftermath, and the continuing presence of those perceived as abusive actors, affected the decision-making of IDPs who chose not to return. In areas like Tikrit and Dour, Shi’a PMF groups were no longer the primary security actor by the time of GPPi’s research; however, they still had free access to and influence throughout this area. In addition, while the number of abuses by PMF units had decreased, there still were reports of PMF fighters engaging in acts of extrajudicial detention or harassment of civilians. The presence of these PMF forces (together with local forces, to be discussed in the subsequent section) also added to the cacophony of security actors in Tikrit, weakening the rule of law and creating a perception of lack of security among local communities. Although the overall return rate was high, those who stayed away noted that the presence and actions of the PMF were a strong factor influencing their choice not to return. A 2017 IOM study analyzed the reasons behind IDPs’ decision not to return, sampling the perceptions of those displaced from eight different areas. Of those eight areas covered by IOM’s study, Tikrit was the one where a fear of militias stood out as the predominant ‘obstacle’ to IDPs’ return. Fifty-eight percent of the IDPs who were from Tikrit city and surveyed for the study presumed that their property had been destroyed by “militias” rather than by ISIL or other groups. In comparison, this metric never exceeded 11 percent in other areas (p. 27). There was also a much higher percentage of respondents from Tikrit than from other areas covered by the IOM study who said their return was blocked by ‘militias’ (29 percent, p. 22 – 23). As IOM reported: “Fear of security actors was the main reason not to return reported by 11% of IDPs from Markaz Tikrit, and 26 percent mention fear of reprisal acts and violence as the second reason not to return. In particular, 76 percent of interviewed IDPs from Markaz Tikrit are very dissatisfied with the role militias are playing in their subdistrict of origin” (p. 62). The example of these IDP perceptions from Tikrit – while only one area – helps illustrate how even past abuses committed by PMF groups and the continuing presence of these forces might have indirectly driven displacement and hampered IDPs’ return.

Extended Control, More Direct Abuses, and Low Return

A final category of issues is that of prolonged displacement and blocked return in areas where PMF forces retained control or significant influence for a sustained period. As noted above, in most areas, PMF were present during the initial liberation or “hold” periods. However, as these areas stabilized and transitioned to more regular Iraqi control, the presence of these Shi’a PMF forces decreased. At that point, PMF often retained some degree of influence or freedom of movement, but did not directly control areas for extended periods of time. However, in a smaller subset of areas, this waning Shi’a PMF control over time did not happen. Shi’a PMF groups retained direct control or very strong influence long after the initial liberation. In these areas, PMF abuses and severe displacement and lack of return tended to persist.

Among the case study areas covered for this research, the most significant example for this category was Baiji district in Salah ad-Din. Much of the population had fled ISIL’s initial occupation and the subsequent, prolonged fighting in Baiji. However, once the area was liberated, looting and further property destruction as well as other types of harassment of the population – most of which was initially attributed to the Hezbollah Brigades and later to AAH – further deterred people’s return. Local officials interviewed by GPPi estimated that 80 percent of the infrastructure in Baiji was severely damaged or destroyed, either over the course of the campaign to remove ISIL or by deliberate looting after ISIL was ousted. Other investigative reporting has suggested that Baiji’s most valuable economic asset, the oil refinery, was looted by Shi’a PMF forces and its parts sold for profit. This not only devastated the community’s economic prospects and livelihood opportunities, but, together with other abusive behavior, sent a message to those who had fled not to return. In addition to such property destruction, PMF forces detained and abused fleeing IDPs and stopped returning individuals and families coming into the area at checkpoints. Amnesty International documented multiple reports of individuals who were stopped at checkpoints in Baiji, detained by the PMF, interrogated, and in some cases tortured. The effects were dramatic: while local government officials and Salah-ad-Din’s governor called for Baiji residents to return to some areas as early as November 2014, only about 25 percent had done so as of March 2018. Follow-up research by GPPi after the primary period of research suggests that the dynamic of PMF domination in Baiji and the corresponding low return rates continued to the time of writing.

Baiji was not an isolated example. Although beyond the scope of GPPi’s research area, even more extreme deliberate and potentially permanent exclusion of Sunni populations was reported in places like Jurf al-Sahkr in Babel governorate.10 and parts of Diyala governorate ( see IOM’s Obstacles to Return report, at p. 54 – 56, and the Iraq Protection Cluster: Diyala Returnees Profile).11 Whether incentivized by lucrative economic resources (as with the Baiji refinery), the proximity to Baghdad (as with Jurf al-Sakhr), or long-standing political interests and agendas (as in parts of Diyala), the PMF groups in these areas mobilized a stronger presence and tighter control, and demonstrated a seemingly indefinite intention to remain. Correspondingly, the displacement and return effects in these areas tended to be more dramatic. Former residents not affiliated with the Shi’a PMF were almost totally excluded and large segments of the population did not return. These displacement effects also differ from those that occurred in the aftermath of the initial liberation. While the latter were more attributable to individual forces’ or units’ bad behavior, and to the general chaotic environment and lack of control, spontaneous acts of revenge or lack of control did not appear to be the primary issue in these areas of prolonged PMF control. Instead, the intent appeared to be similar to the rationale driving the Kurdish takeover of some of the areas in the Disputed Territories: exclusion or marginalization of the former population as a strategy for future control.

Local Know-How, Local Revenge: The Role of Locally Mobilized Forces in Driving Displacement and Deterring Return

Although the PMF are most strongly associated with the pre-existing Shi’a militias discussed above, the force as a whole is diverse, drawing from all regions, ethnicities and political groups in Iraq. In particular, as areas in northern and central Iraq were liberated, local communities or actors sponsored or responded to calls to mobilize volunteer forces. These local PMF units tended to be smaller and subordinate to the larger PMF groups; nonetheless, their actions had distinct repercussions for displacement and return. In theory, having local forces might lead to better civilian protection and faster returns because local forces are expected to be more protective of and trusted by their communities than outsiders. However, in practice, these local roots came with local ambitions, interests and grudges. Many of these local forces were mobilized along sectarian, ethnic or political lines in mixed or divided communities. Instead of protecting the local population, many of these groups used their positions of authority to exact revenge or disadvantage rival individuals or groups. IDPs or returnees, who were frequently in a vulnerable position, often bore the brunt of such retaliation.

These local PMF forces tended to be small and not very strong militarily, with most ranging from a couple hundred to sometimes a few thousand fighters. They largely played a subordinate or sometimes only perfunctory role in the initial clearing and hold operations. Although each force had a nominal leader (frequently a local political or community figure), most of these local PMF units were recruited by or had some reporting line to one of the larger PMF forces (more information on the recruitment and control of local forces here). The Badr Organization and AAH were particularly active in recruiting or taking on local affiliates in Salah ad-Din and other areas of operation. In Ninewa and Anbar, US forces provided direct support to local Sunni tribal PMF units through the Iraqi government, which enabled these local forces to have slightly more independence from leading PMF groups. For the most part, these smaller local forces were not strong militarily and did not function autonomously. However, a few of the groups had greater capacity, manpower and resources, and were able to dominate a local area or carry out significant operations on their own. These areas tended to be the ones where most of the issues of blocked returns for or abuse of IDPs by local forces manifested.

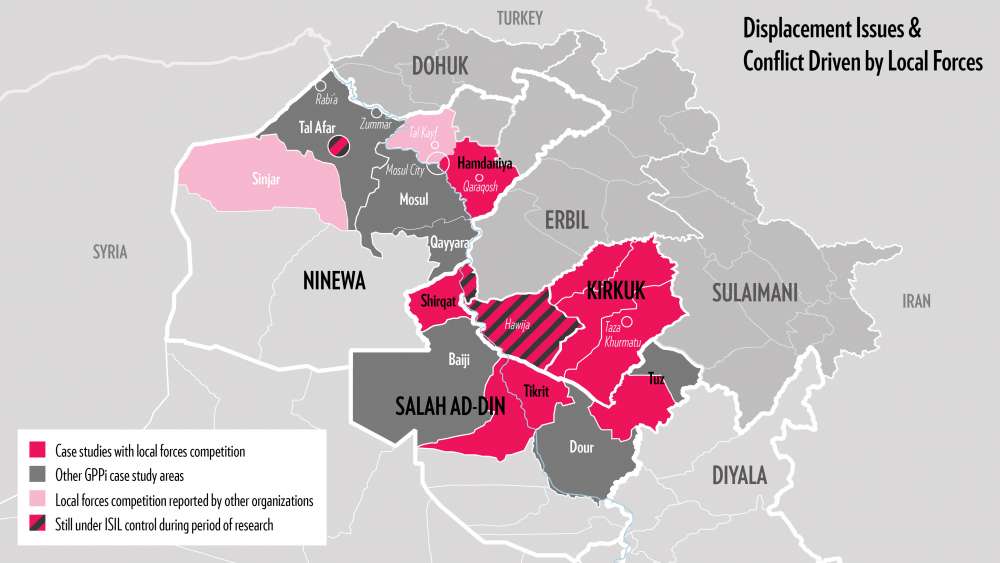

The map below illustrates some of the places in GPPi’s case study areas where local forces issues manifested. Although not the only areas where local forces perpetrated abuses or affected displacement and return, examples from these case study areas will be used to illustrate this larger dynamic in the remainder of this subsection.

The starkest examples of forced displacement and blocked return perpetrated by local forces related to the Shi’a Turkmen PMF forces in Tuz and Kirkuk governorate. As the larger Shi’a PMF groups (with Badr in charge, but accompanied by a range of other PMF factions) entered Tuz to halt or reverse ISIL’s course in 2014, they mobilized what effectively became local franchises or affiliates from among the Shi’a Turkmen population in Tuz. After the Shi’a PMF began more limited operations in Kirkuk in early 2015, they used the same strategy, again among the Shi’a Turkmen population. The larger PMF forces invested more training and resources in these Shi’a Turkmen affiliates than they did for most other local forces, perhaps in part because the larger Shi’a PMF forces had a more limited presence in Kirkuk and had agreed to withdraw from Tuz after its liberation (in both cases this was due to agreements with the KRG; see the description of control in the Tuz and Kirkuk case studies). Priming strong, locally rooted Shi’a forces was a way for these larger PMF units to keep a foothold of control in both areas. The shared sectarian outlook of these national and local forces was likely also a contributing factor.

At the time of GPPi’s research, Shi’a Turkmen forces held significant territory in Tuz and a smaller corridor of territory in Kirkuk, both relatively autonomously. They still reported to and consulted with their larger parent PMF forces, but the latter were less directly engaged in directing day-to-day activities. In both of these areas, the degree of local versus Shi’a PMF engagement shifted following Baghdad’s re-assertion of control over Kurdish-held territories in October 2017; however, Shi’a Turkmen PMF were still a strong force in Kirkuk and Tuz after this territorial shift, with an even wider area of operations and remit. For example, at the time of GPPi’s research in Tuz, local Shi’a Turkmen PMF maintained control of half of the district capital, Tuz Khurmatu city, and much of the southern half of the district, while the KRG retained control in the other half. When Kurdish forces were forced to leave in October 2017, PMF forces (not just local, but also the leading PMF forces described in the previous section) were free to carry out operations throughout the district.

Because local Shi’a Turkmen forces were in control and managing operations in these areas up until 2017, many of the numerous issues of forced displacement, blocked return and abuse of IDPs during this period can be attributed to these local forces. It is likely that the larger parent PMF forces, such as Badr or AAH, were tacitly aware of such abuses and thus are also to blame; however, in many cases, local actors appeared to be the ones motivating and driving these violations. Shi’a Turkmen PMF groups perpetrated numerous abuses and retaliatory acts against and destroyed much of the property and restricted the return of non-Shi’a Turkmen groups. Abuses by Shi’a Turkmen PMF (from petty harassment to mass arrests and targeted killings of community leaders) effectively emptied the formerly mixed neighborhoods of Tuz Khurmatu city of their Sunni Turkmen and Sunni Arab populations. At the time of research, locals from these neighborhoods estimated that only 5 – 10 percent of the original Sunni Arab population and 10 percent of the Sunni Turkmen population remained. Reports of Shi’a Turkmen attacks on Sunni Arab and Sunni Turkmen communities were fewer in areas outside of Tuz Khurmatu because there were few non-Shi’a Turkmen left. While nearly all families from Amerli’s three Turkmen Shi’a villages returned to their homes shortly after ISIL’s ouster, no Arabs or Sunni Turkmen (an estimated 15,000 families or more) had returned to areas controlled by the PMF. In their absence, Shi’a Turkmen PMF engaged in significant destruction of homes and property in non-Shi’a Turkmen communities. According to Human Rights Watch, the patterns of property destruction suggested an effort to permanently change the population dynamics.12 Locals whom GPPi interviewed tended to agree with these findings and argued that the property destruction in PMF-controlled Tuz was motivated by sectarian politics and an attempt to reshape who controlled certain areas within Tuz.

After the withdrawal of Kurdish forces from half of Tuz in October 2017, there was an outbreak of violence and clashes, particularly in the city of Tuz Khurmatu. This prompted a new round of displacement of Kurdish civilians, with estimates of up to 30,000 displaced, and further instances of retaliatory violence and property damage in their wake. These events took place after the period of GPPi research and represent another set of displacement issues or factors in that there were more actors involved than purely local or even national PMF units. Political uncertainty and reversal of control was likely as much of an issue as the presence or conduct of LHSFs. Nonetheless, Shi’a Turkmen PMF reportedly participated in retaliatory violence and their past behavior and treatment of civilians from outside the Shi’a Turkmen community likely contributed to the decision of many Kurdish residents to flee the area after they learned that these forces would be taking full control.

Although Shi’a Turkmen PMF controlled a smaller area in Kirkuk than they did in Tuz, similar patterns manifested in the zones of PMF control. The areas around Bashir in Kirkuk had traditionally been Shi’a Turkmen villages, surrounded by predominantly Sunni Arab villages. As of fall 2017, one-third of the Shi’a Turkmen families who had been displaced had returned, as opposed to a complete lack of Arab returns.13 A local official said that Turkmen PMF (in cooperation with Peshmerga and local police) actively stopped Arab IDPs at checkpoints, blocking them from returning. In 2018, Human Rights Watch reported continued forced displacement of Sunni communities in Kirkuk and destruction of their property by PMF fighters (in cooperation with Iraqi forces, who assumed control in late 2017).

Among the different local forces examined in GPPi’s research, the Shi’a Turkmen PMF exhibited the most abusive behavior toward other groups, creating the most concerning displacement and return patterns in their areas of operation. This is in part because they were stronger, enjoyed greater autonomy, and controlled a wider area than most other local forces, giving them the opportunity to exercise their agenda virtually unchecked. The connection with the larger Shi’a PMF groups likely helped, too. While the research findings strongly suggest that this severe exclusion and intimidation of non-Shi’a Turkmen communities in Tuz was largely initiated and driven by the local Shi’a Turkmen forces, it is likely that these abuses were known and possibly encouraged by their larger PMF parent forces. At a minimum, they did little to discourage or stop them, and the protection of these very powerful groups enabled the local PMF forces to do as they pleased.

Similar patterns of PMF protection and unchecked abuses by local forces manifested on a smaller scale (given the smaller scope of territorial control) in the Ninewa Plains (near Mosul) in 2017. A PMF-backed Shabak force controlled many of the key checkpoints in the southern Ninewa Plains, particularly around the entrance to Mosul. These Shabak forces had a thuggish reputation and their position of control appeared to be a factor deterring other groups from returning (levels of property destruction; lack of education, livelihood opportunities, or services; and comfortable resettlement elsewhere also influenced many IDPs’ decision not to return). Shabak communities rapidly returned to their home communities in the Ninewa Plains and even expanded into neighboring villages and cities, while most of the Kaldo-Assyrian or Christian and Sunni Arab communities that had previously dominated villages or cities in this area stayed away. The small, largely Christian city of Qaraqosh (one of the areas of GPPi research) saw virtually no return. Although this was partially due to other factors,14 these tensions between the Christian and Shabak communities (p. 16 – 8) were a significant driver, as was mistrust of the Shabak militias, who overwhelmed the local Christian forces in both numbers and capacity. Other organizations have reported similar tensions between Shabak or other Shi’a PMF forces and LHSFs mobilized from the Sunni tribal or Kaldo-Assyrian communities in other areas of the Ninewa Plains (see for example this Sanad profile of the nearby Tal Kayf area, p. 22 – 23).

All of the above-mentioned examples of abuse or discrimination committed by local forces have occurred in areas where local ethnic or sectarian rivalries bear heightened significance due to the diversity in these areas as well as long-standing inter-group tensions and the connection with broader political contests for control. However, local forces used their position of power to retaliate against rivals even where such larger communal splits and political fault lines were absent. In areas that were predominantly Sunni Arab, the divisions often manifested along tribal divisions or lines of local political rivalries. In Tikrit, for example, the extensive looting and property damage that took place during the initial displacement was said to have contributed significantly to residents’ flight from the city. As noted in the section above, IOM’s study on obstacles to return suggests that this property damage (which 57% of the IDPs from Tikrit attributed to ‘militias’ in the area) strengthened their reluctance to return (p. 27, 62). This initial looting and violence was publicly blamed on larger Shi’a PMF forces. However, GPPi’s research suggests that much of the violence was initiated and perpetrated (and, on some accounts, even led by) local Sunni PMF groups, who sought revenge against tribal rivals that had sided with ISIL. This is not to suggest that the Shi’a PMF did not also play a role in producing these significant displacement and return issues, but simply to underline that, in terms of causality, local actors and local motivations were sometimes as much to blame as the outsiders.

Similar examples of local, inter-tribal disputes interacting with LHSF-driven displacement manifested in other Sunni tribal areas, such as in Qayyara in Ninewa. However, many of these appeared connected with the “ISIL families” issue, and so will be further analyzed in the subsequent section.

Collective Punishment, Collective Blame: “ISIL Families” and Broader Government and Community Culpability

One of the most significant migration issues surrounded the forced displacement and blocked return of so-called ISIL families. It was an issue that many LHSFs contributed to, but often in partnership with or at the behest of a wider circle of government and community actors. The overall high level of resentment and hostility toward ISIL fueled a sort of collective punishment approach targeting anyone associated with ISIL members. This included not only those who had perhaps only cooperated with ISIL under duress, but also the wives, children and extended relations of those deemed to be ISIL members, which were commonly referred to as “ISIL families.” Severe abuse and discrimination against ISIL families strongly contributed to displacement and blocked return dynamics across all areas of GPPi’s research for this study.

Allegations of abuse and mistreatment against ISIL families manifested broadly across North and Central Iraq, including in Anbar, Babel, Diyala, Salah ad-Din, Ninewa, and Kirkuk governorates. Many men with any kind of ISIL association were detained or disappeared, and their wives, children or other family members faced severe harassment, discrimination, and sometimes even direct assault. For example, in Qayyara, a predominantly Sunni Arab subdistrict south of Mosul, those whom GPPi interviewed for this research reported that other members of the community threw grenades into the yards or at the homes of those they deemed to be “ISIL families.” Other homes of ISIL families in the area were burned or damaged (p. 36).

Such abuses were frequently carried out by members of LHSFs, but also by many other actors in the community. In fact LHSFs and Iraqi or Kurdish security forces as well as local officials often worked in tandem. For example, while Iraqi security forces carried out many detentions of alleged ISIL associates on their own, 15 they also often cooperated with PMF forces on these detentions (PMF units like Badr have had a long history of close cooperation with Iraqi forces, in particular a sort of “revolving door” between Badr members and members of the Federal Police; see examples here and here). During GPPi’s research in Qayyara, residents reported that some of those detained from their homes (presumably because of their ISIL affiliation) were detained by Shi’a PMF groups who worked closely with the Federal Police.16 Local security officers interviewed confirmed that, in cases where it was too sensitive for them to directly detain someone they or the community suspected of being an ISIL associate (presumably because there was insufficient evidence), they could ask nearby PMF forces to do so. The PMF Commission denies that its forces engaged in detention and Iraqi officials do not recognize that PMF units are allowed to detain individuals. However, reports of such tacit cooperation recurred throughout GPPi’s research areas, and are also supported by other organizations’ research and documentation.17

Such abuses, harassment and intimidation caused families or individuals who would be a likely target to remove themselves from communities or deterred them from returning. More directly, ISIL families were sometimes forcibly displaced to IDP camps, and their homes or property were destroyed in their absence to deter them from returning. This happened across the liberated areas. One interview with a local community advocate engaged in trying to negotiate the return of such families provides a sense of the scope: he said that, as of summer 2018, there were an estimated 96 “isolation camps” — the term used to describe the places in IDP camps where ISIL families were held.18

Once removed to IDP camps, ISIL families were typically kept separate from other IDPs and prevented from leaving. In some cases, they were not allowed to have access to mobile phones or legal support, placing them in what were effectively detention-like conditions, according to Human Rights Watch. Amnesty International reported that many of the ISIL families in these positions, which were usually headed by women, were denied the same aid or health access granted to other IDPs in the camps (sometimes directly by the PMF operating in or securing the camp area). Some of the affected women were sexually exploited and assaulted.

LHSFs were frequently and directly involved in such forced displacement. One of the most significant (documented) examples of this type of forced displacement happened in Shirqat, a district that was one of the last areas to be cleared and that many locals viewed as one of ISIL’s strongholds. In early 2017, because of ongoing security concerns and the suspicion of Shirqat residents, security forces — including notable engagement by both Shi’a PMF and local Sunni tribal PMF units — forced 110 to 125 so-called ISIL families to relocate to the Shahama IDP camp. Although the incident was so controversial that the political authorities immediately disavowed any responsibility, research suggests that both the Salah ad-Din governorate council and the local council in Shirqat authorized this forced displacement. As such, the illegal forced displacement and de facto detention of these families was executed by LHSF groups, but on the orders of Iraqi authorities.

In other areas, communities and tribal hierarchies took the lead. In Qayyara, a tribal sheikh told GPPi that a meeting of tribal elders, which local government officials also attended, had determined that ISIL families should be expelled and forced into IDP camps. Another elder said that the mothers, wives and other relatives of alleged ISIL supporters or collaborators had already been sent to live in the Jeddah IDP camp in Qayyara city. In these cases, while the presence of Sunni tribal PMF groups19 and their availability to enforce the displacement may have contributed pressure, the driving force behind it was the community’s will. Similar reports of informal pressure, backed by local authorities and LHSFs, recurred and continued throughout Sunni tribal communities in Ninewa, Salah ad-Din and Kirkuk.

Once displaced, ISIL families as well as other IDPs without connections to them were blocked from returning. Before IDPs were allowed to return to their homes in liberated areas, they had to be screened or ‘vetted’ for possible ISIL affiliation. The lack of transparency in this process and the ad hoc nature of its implementation meant that such vetting was frequently used to prevent ISIL families from returning even if they did not pose a security threat that should to justify their exclusion.20 In some cases, there were also direct governmental or tribal edicts that forbade ISIL families from returning to particular localities. For example, Amnesty International (p. 35 – 36) reported several accounts of the Shirqat local or tribal authorities (accounts differed on this) passing a law or edict banning that wives of so-called ISIL families from returning until they remarried.

LHSFs tended not to be directly engaged in producing such edicts (although Amnesty found one example of a supposedly PMF-instituted return ban in Hamam Alil, south of Mosul; see p. 36). However, they were strongly engaged in enforcing these bans or discriminatory vetting practices through their control of checkpoints. For example, in IOM’s study of obstacles to return, stoppages at checkpoints were identified as the second most common instrument for blocking IDPs’ return. Moreover, ‘militias’ and the Asayish (the KRG internal security forces) were the actors that were reported to be most frequently involved in stopping IDPs from returning (p. 14).

The broad discrimination enabled by the poorly managed vetting process and the general stigma against ISIL families was also problematic because it facilitated some of the other politically, sectarian or ethnically motivated discrimination or abuses described in the preceding sections. As the previous section has suggested, in many cases, abuse or blocked return was connected to other political agendas or motivations of control. As such, the “ISIL association” moniker (as a valid reason to reject individuals or families) helped legitimize and enable discriminatory return policies writ large, and thus contributed to overall politicization of displacement issues.

Divided Authority and System Effects

A last point to consider is how the larger phenomenon of LHSF mobilization affected the management of migration issues. Three clear trend lines stood out in terms of these systemic effects: (1) The effects of a multiplicity of actors on the rule of law and perceptions of insecurity; (2) how multiple actors and unclear mandates inhibited an effective administration of migration; and (3) how the presence and/or reputation of LHSFs complicated humanitarian actors’ work.

Rule of Law Effects

One consequence of the post-2014 security response and the mass mobilization and deputization of sub-state and local forces may have been that it exacerbated displacement issues and complicated return, recovery, and re-establishment of rule of law. Several of GPPi’s case study areas saw the presence of a multitude of LHSFs with obscure lines of authority and often weak command and control structures. In many cases, these groups were competing with each other, resulting in frequent armed clashes and other acts of retaliation or tit-for-tat violence. These multiple forces also were frequently stronger (having more men and more arms) than the local police or authorities, making it difficult to keep them in check. Many of these quickly mobilized and scantily vetted forces included criminals and former insurgents. All of these factors contributed to higher levels of criminality, impunity and overall insecurity, which undermined the rule of law environment. These negative rule of law effects were most prominent in urban areas like Mosul, Tikrit, or Tal Afar city. However, such effects were also present in other non-urban areas where multiple, competing LHSFs with loose discipline or control were present.

Information gathered through qualitative interviews suggests that this erosion of the rule of law environment and perceptions of insecurity had many negative consequences in the case study areas. Most relevant for this essay, they helped to deter IDPs from returning and resettling or, in some cases, provoked renewed displacement. Insecurity in the area of origin has consistently been one of the top reasons for not returning home given by IDPs (see examples of these findings here, here, and here). There are multiple factors driving those perceptions of insecurity, including active fighting in some areas. However, weak rule of law and increased criminality and lawlessness are certainly important contributing factors.

In addition to GPPi’s observations, other studies have found a strong correlation between the presence of multiple security actors and a lack of return of IDPs. IOM conducts a regular (monthly) survey to assess conditions of return across Iraq, and one of the data points or indicators it monitors is whether four or more security actors are operating in the area. Those involved in monitoring and collecting this data said that this observation of ‘four or more’ security actors present was one of the strongest indicators for return ‘hotspots,’ meaning areas where the conditions for return were poor and displacement was prolonged.21 A November 2018 report by IOM further contextualized this within a general discussion of security factors: “[r]esults from the Return Index indicate that a location with the presence of a multiplicity of security actors is significantly less likely to have returns than a location with a smaller number of actors — this holds particularly true within the districts of Khanaqin, Telafar, Muqdadiya, Khalis and Tooz Khormatu” (p. 17). Although not conclusive, GPPi’s and IOM’s data both suggest that there is a correlation between the proliferation of multiple security actors in an area and worse displacement and return effects.

Complex Migration Management

The presence of multiple subgroups and security actors in general also created negative migration trends by hampering the administration of return. In the same November 2018 report noted above, IOM suggested that one reason that the presence of multiple armed groups might correlate with a lack of return in the respective areas was by inhibiting the administration of return: “[m]ultiplicity oftentimes brings confusion as to who is in control of locations and which protocols residents need to follow, issues ultimately linked to safety perceptions and affecting the likelihood to return” (p. 17).

This was most apparent in the way that LHSF participation in the vetting system inhibited smooth or regular return. Before IDPs were allowed to return to their homes in Baghdad-controlled areas, they had to be screened or ‘vetted’ for a possible ISIL affiliation by submitting their personal documentation to the Operations Command Center in the governorate to which they wanted to return. These centers were a joint venture by the Directorate of Security Intelligence, the National Security Agency, Iraqi Special Forces, the Iraqi army, police, and armed groups. However, many of these security actors maintained their own databases of suspected ISIL affiliates and each family member had to receive clearance from all databases. Not only was this process lengthy,22 but the databases often contradicted each other and the process by which an individual might be blacklisted was unclear. LHSFs were yet another layer within this already complex system of vetting and return. Stronger PMF forces reportedly kept their own databases and lists, and could submit information to influence who was on the official lists of blocked individuals.

In addition to adding to the overall cacophony of overlapping vetting lists and databases, LHSFs made the application of vetting even more irregular at the point of return. Many LHSFs were in control of checkpoints, which is where the final decision on whether permission to return or to pass through a transit point en route to return would be permitted. Although in theory all LHSFs manning checkpoints would have had the same lists of who was authorized to return, and regular procedures for permitting return, in practice, the ways that these rules were implemented was as numerous as the LHSFs themselves. This was partly to do with multiple lists of vetted individuals as well as the fact that they were poorly updated. But it is also because many LHSF forces at checkpoints applied their own rules and scrutiny. The contradictory and only loosely regulated vetting process allowed ample opportunities for LHSFs to exploit their position of control to allow IDPs in or not, regardless of the formal paperwork.

As a whole, many humanitarian actors objected to the way that this vetting process placed security actors in control of managing return flows, to the often discriminatory standards and processes developed, and to the irregular way in which they were applied. However, the fact that poorly screened and controlled LHSFs could significantly influence and shape such processes made them even more problematic.

Challenges for Humanitarian Actors

The large presence of LHSFs also impacted displacement and return by making it harder for humanitarians to administer aid and returns. Humanitarian actors played a critical role in providing for the millions of IDPs and returnees, but their ability to do so depended on access and on cooperation with security actors in charge of local areas. This was hampered by the predominance of LHSFs in a number of ways. First, the sheer number of armed groups and unclear lines of authority made it difficult to establish the sort of working relationships necessary to develop humanitarian operations. Given the complexity and constantly fluctuating nature of the security sector (in part due to the plethora of actors), it was not always clear who was in charge, and how long their influence or control would last.

Second, many of the LHSFs in control of local areas had a poor reputation and a record of abuses. As such, humanitarian actors were often reluctant to work with them, either out of concern for staff safety, due to reservations that working with these actors would violate humanitarian principles of neutrality and ‘do no harm’, or that such cooperation might imperil future funding. As noted earlier, several of the most prominent PMF groups were either on US terrorist watch lists or had members or leaders who were (notably Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who oversees overall PMF operations). By establishing a relationship with one of these armed groups — even if intended to facilitate humanitarian aid — humanitarian organizations risked violating material support to terrorism laws in the US, an important donor.

However, avoiding working with these actors – the major PMF forces in particular – posed a dilemma for humanitarians: these LHSFs controlled major swaths of territory and their permission or cooperation might be required in order to deliver aid or facilitate return to some areas. Not working with them would result in vulnerable populations receiving little or no support. A small number of humanitarian groups ultimately developed working ground relationships with PMF and those that did were able to provide assistance in areas where other NGOs or aid organizations were unable to work. These relationships, where established, could be productive – one aid worker interviewed for this research found the PMF organizations the interviewee had worked with to be extremely open to facilitating aid delivery, noting that they tended to respect the lines drawn by the organization in terms of maintaining their independence and neutrality. However, these types of partnerships were the exception rather than the rule, meaning that many vulnerable populations in PMF-controlled areas received insufficient assistance. In addition, those organizations that did work with PMF in this way kept their operations quiet, which inhibited broader cooperation and administration of aid.

Conclusion

Returning to the original prompt for this research and this essay: did the mass mobilization or deputization of so many LHSFs exacerbate displacement and impede return in Iraq? As a whole, the evidence suggests that it did, that LHSFs produced a number of negative consequences for displacement and return. Direct abuses, harassment or discrimination by LHSFs sparked fear in parts of the civilian population, spurring displacement or deterring return. LHSFs participated in the forcible displacement of civilians and blocked the return of IDPs in areas or checkpoints they controlled. The presence of so many competing security actors also impaired the overall climate for return and hampered the administration of migration policies and support. In short, the ways that LHSFs have negatively influenced displacement or return are as varied as the types of LHSFs themselves.

However, for many of the problematic trends described above, LHSFs were not the sole culprits. In many cases, the abuses, rights violations, or discriminatory return policies perpetrated by LHSFs were instigated by or happened at the behest of larger community or political actors. Abuses committed by PMF forces in the wake of liberation as well as looting, acts of retaliation, extrajudicial or illegal detentions, or harassment of segments of the population were often carried out alongside Iraqi forces, suggesting tacit cooperation, if not direct complicity. Abuses and exclusionary strategies by local forces very frequently reflected larger ethnic, sectarian, or tribal splits within those communities, and were encouraged or abetted by other formal or informal actors in the community. Many of the worst instances of forced displacement or blocked return, such as those against purported ISIL families or against Sunni Arab communities, were in conformity with KRG, governorate or local Iraqi official policies. From this perspective, while LHSFs were certainly at the tip of the spear of discriminatory and violent displacement and return policies, their actions reflected a deeper and more problematic politicization of displacement. The displacement and (blocked) return of populations was instrumentalized by all sides — from national to local stakeholders, on the Baghdad and the KRG side, by state and sub-state actors and forces — and used as a strategy for political and territorial control. While this has been a long-standing issue in Iraq, and a tactic used consistently at different historical periods, it should be noted that this is not the case for all post-conflict or conflict environments, or at least not to the same degree.23

Nonetheless, although LHSFs were not the sole cause of problematic migration trends in Iraq, their presence appears to have exacerbated them. LHSFs did not invent discriminatory or exclusionary displacement policies, but their presence heightened the risk of this happening in many areas. Because LHSFs were often mobilized along existing fault lines, there was a greater likelihood of them using their dominance in certain areas to disadvantage or persecute other rival or hostile groups. In addition, local control by these often partisan security actors offered new opportunities for local, national and regional actors to exercise exclusionary strategies. Beyond these deliberate, exclusionary policies, the last section also highlighted a number of indirect or unintended consequences of the mass mobilization of so many substate actors. The presence of so many armed actors (by virtue of the mobilization of so many LHSFs) and convoluted lines of control weakened the rule of law and contributed to an environment not suited for return and recovery. The presence and actions of LHSFs made an already ad hoc and complex returns management system even more opaque and arbitrary, and hampered the work of humanitarian actors.

Lastly, the nature and character of LHSFs appears to have made a difference. Although there was variation from one type of force to another, LHSFs as a whole appeared to be more undisciplined and abusive, and civilians (including would-be returnees) did not trust them. There is certainly no shortage of criticism of Iraqi forces’ misconduct nor of that of Peshmerga fighters (some of which was described in the first section). However, in general, the different PMF forces — local and national — demonstrated less discipline and professionalism than state forces and tended to be more frequently associated with abusive behavior. As the Iraqi government and security forces resumed their control in different areas, return flows tended to increase — a pattern observed across all of GPPi’s research areas and also supported by other work tracking migration patterns in Iraq. GPPi’s interviews with those in liberated areas suggested that this was in part because civilians simply trusted and preferred Iraqi officials and security forces to LHSFs. Even those civilians or local authorities with relatives in different PMF forces tended to say that they preferred that the responsibility for security be in the hands of regular, state security forces. 24 These findings suggest a number of important recommendations or cautions going forward, both for the immediate situation in Iraq and more generally for future situations where LHSFs predominate: