How Democracy Promoters Can Respond to Populist Protests

The Case of Brazil

What can governments and international organizations promoting democracy abroad do when mass populist protests are directed against liberal democracy, their own political goals – or both? In such contexts, international democracy promoters might feel that their hands are tied. Populist protests, after all, involve local civil society actors bringing people to the streets to make political demands, even when those demands are problematic. But this study shows that external actors do have strategic options.

It does so by examining the case of Brazil, where three right-wing populist protest groups played a crucial role in the successful partisan campaign to impeach former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and contributed to the election of the anti-democratic President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. Although the three groups differed in the extents to which they threatened Brazil’s democratic institutions, external democracy promoters working in the country failed to develop nuanced or joint responses.

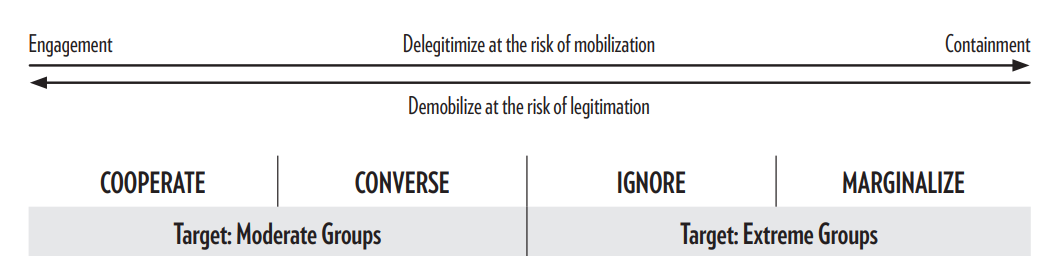

To help international democracy promoters appropriately respond to populist protest groups, the study develops a typology that includes four approaches: cooperate, converse, ignore, and marginalize. This typology ranges from engagement to containment. As a rule of thumb, engagement approaches (cooperate and converse) should be applied to more moderate actors, while containment approaches (ignore and marginalize) are suitable for more extreme groups. But democracy promoters will still need to assess the trade-offs that each approach entails.

In Brazil, democracy promoters only employed containment approaches toward the key populist protest groups. This was not only because most democracy promoters lacked well-developed response strategies in the first place, but also because they did not consider themselves – as external actors – positioned to approach these groups.

Democracy promoters also faced significant obstacles in the leadup to Rousseff’s impeachment over which they had limited control. On the one hand, left-leaning democracy promoters’ actions were restricted by their civil society partners, who were unwilling to cooperate or converse with populist protest groups, and instead sweepingly criticized them all. On the other hand, the populist protest groups were themselves reluctant to engage with new external partners at the time.

But democracy promoters missed a potential later window of opportunity for engagement with the same groups. This window opened in 2021, when both left-wing and right-wing actors filed a joint impeachment request against Bolsonaro and started to organize protests around this goal – but kept their mobilization efforts separate. Democracy promoters did not attempt to mediate between the two camps.

Importantly, this development raises the question of whether ignoring and marginalizing populist protest groups are always the right strategies for promoting democracy. In the case of Brazil, engagement approaches toward populist protest groups could have arguably helped build a counterweight to Bolsonaro and reduced the threat he posed to liberal democracy in the country.

Based on this analysis, the study presents three recommendations for international democracy promoters:

- Develop analytical tools to mitigate biases in the assessment of populist protest groups.

- Engage with moderate populist protest groups and contain extreme ones.

- Establish a network of politically diverse democracy promoters and prioritize defending democracy.

Read the full study to learn more about the Brazilian context and what the rest of the world can take away from it.

This study was funded by the Heinrich Böll Foundation.