Ghosts of the Past: Lessons from Local Force Mobilization in Afghanistan and Prospects for the Future

Since 2001, the international military and the Afghan state have mobilized a range of local or community-based forces to fill security gaps and confront insurgent threats in the country. One of the longest-running initiatives, the 2010 Afghan Local Police (ALP) was set to be defunded in September 2020, while other local forces, the Afghan National Army Territorial Force and a more shadowy group of state-supported community forces known as the Uprising Forces, appeared set to continue. Part of a three-year project exploring local, hybrid, and sub-state forces, this joint research report by GPPi and the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) surveys the landscape of local forces mobilized since 2001, how well they delivered on the goals of community protection and conflict stabilization, and how these forces play into the prospects for peace, demobilization, and reintegration in Afghanistan.

Overall, our research suggests that, while local defense forces can bring benefits in securing territory and protecting communities, they will not work in all areas. Despite some recognition of the risk of co-option at the outset, pressure to roll the ALP out in areas where it was not appropriate, as well as failure to develop it slowly enough to enable meaningful institutional or community controls, led to more negative than positive examples of local forces. Where the ALP has been mobilized in environments to which it is not suited, or where it has been mismanaged, it has brought significant harm to local people, and they have suffered lasting damage.

The full report as well as an executive summary are available for download. A parallel version of the report exists on AAN’s website.

For a summary of the main findings, keep scrolling to explore our photo essay.

The full report was last updated in October 2020.

Ghosts of the Past: Implications for the Present

Afghanistan’s history has long been shaped by the interaction of local forces with the state – from dynastic rulers’ co-option of tribal forces, to the emergence of mujahedin forces (like those pictured here) following the Soviet invasion, to the anarchic militia contests that stood in for politics in the 1990s. Particularly since the 1980s, militias have been mobilized and re-mobilized ad nauseum, along ever-deepening factional, ethnic, tribal, and other solidarity lines. These commander networks and solidarity lines were never fully demobilized or dismantled after 2001, and later efforts to rebuild the Afghan state or to mobilize local forces would happen against this backdrop of pre-existing militias, factions and commanders.

After 2001, commanders and political factions took advantage of international funds and a market for force to re-hat and sustain their forces. Many militias were incorporated wholesale into the new Afghan security forces, while others became auxiliary forces to Special Forces and the CIA. By 2005 many warlords and strongmen funneled their militias into private security companies and won lucrative contracts guarding foreign bases, public highways, businesses, etc. In 2006, the Afghan government (supported by NATO) tried to supplement struggling police forces in southern Afghanistan by enlisting tribal forces and strongmen militias as the “Afghan National Auxiliary Police” (pictured below). The program was short-lived but would preview some of the hybrid force initiatives discussed below. All of these different post-2001 quasi-state and semi-privatized forces proved problematic. The re-hatting of militias undermined disarmament and demobilization efforts, and it kept power in the hands of warlords and strongmen. They used their power to prey on the population or further criminal enterprises. All of this undermined the Afghan state and contributed to a Taleban resurgence.

A Break With the Past? The Afghan Local Police

By 2009, the Taleban were gaining momentum and the Afghan state appeared too weak to stop them. It had no presence across much of rural Afghanistan and was viewed as corrupt and predatory. Inspired by the success of the ‘Sons of Iraq’, US Special Forces instead turned to tribal and community actors as the ideal counter-insurgents against the Taleban and began testing models of local defense forces in strategic locations across Afghanistan. The theory was that forces recruited by and accountable to communities would bring local know-how, intelligence and legitimacy, and would also be more committed to protecting (as opposed to abusing) their communities. These local defense initiatives were formalized in August 2010 as the Afghan Local Police, under the Ministry of Interior, and were quickly established in communities across Afghanistan (including Kapisa province, as pictured below).

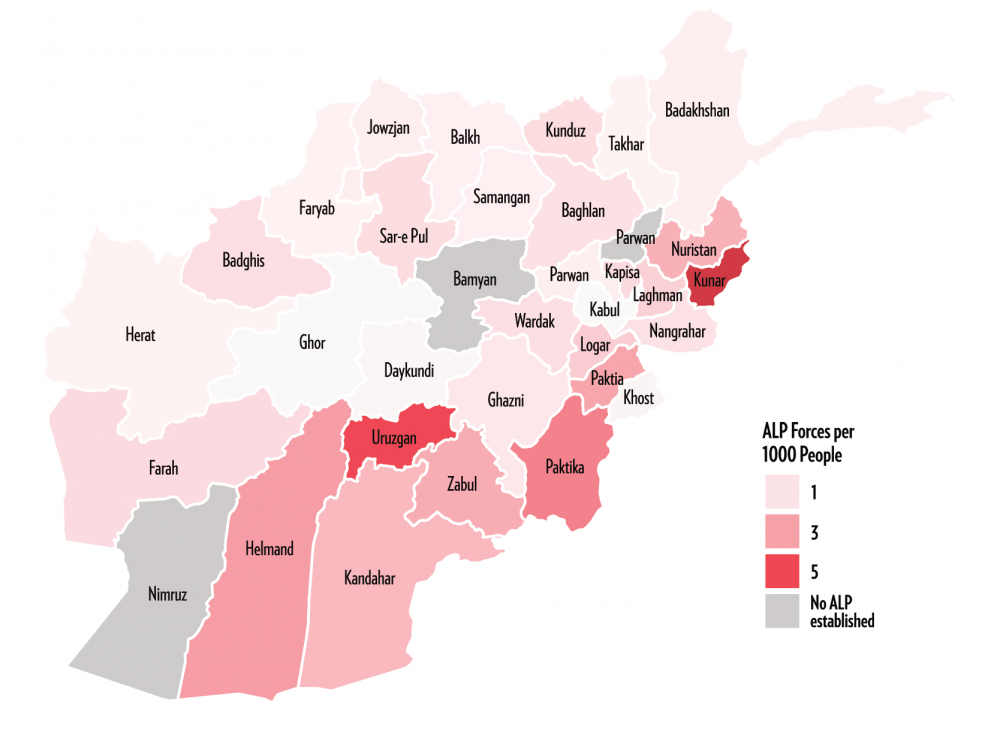

While the ALP model designed by Special Forces called for winning the buy-in of local communities and only standing up ALP where the community dynamics were ripe for it, this slow and limited model clashed with political and security imperatives. The ALP expanded rapidly, from just over one thousand men when authorized at the end of 2010 to 17,000 by the end of 2012. By January 2015, the ALP had expanded to roughly 28,000 men, and by 2017, when the data for the map below was obtained, existed in 31 or 34 provinces.

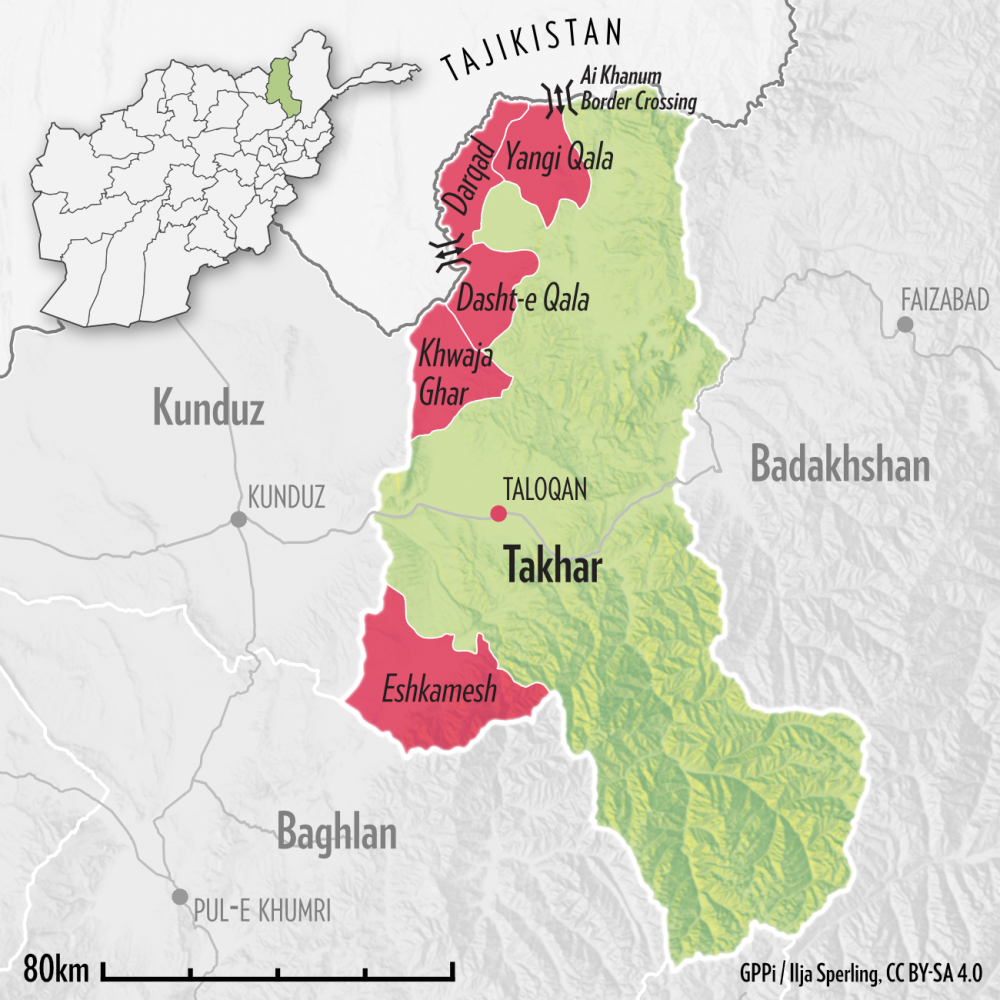

The initial ALP model included safeguards against forming ALP units in areas where they would likely generate conflict or become predatory militias as well as of only mobilizing ALP units in communities that wanted them — and with locals’ input and consultation. But these safeguards were largely overridden by the demand for rapid expansion and by political interference from Afghan politicians and powerbrokers. The case studies of ALP in Takhar province and in Shajoy district of Zabul provide two examples of the consequences of this. Takhar has long been a key transit point for smuggling and had a history of problematic commander politics. Despite these red flags, Afghan powerbrokers successfully pressed to extend the ALP program to the north, and the results were predictably bad. Local powerbrokers in Takhar easily co-opted the ALP, using it as a vehicle to legitimize and fund their militias and security rackets.

The ALP in Takhar functioned as little more than predatory “drug-runners,” according to witnesses and the UN. It acted as “ALP by day, militia by night.” Similar lax screening and lack of community consultation created an equally disastrous force in Shajoy district in southern Zabul province. US forces and provincial officials tapped a known commander who brought his own men, most from outside the district. Not beholden to the community, the Shajoy ALP engaged in extrajudicial killings, mistreatment of detainees, and sexual assault of girls and women, among other abusive behavior. Shajoy citizens complained but were only able to force the ALP commander’s dismissal once the international forces and provincial officials who had backed him rotated out.

The ALP also inspired other copycat forces, many of which were more thinly regulated. Powerbrokers who could not get their forces into the ALP maintained militias as “unofficial ALP.” In 2012, what became known as the ‘Andar Uprising’ in Ghazni province generated a new type of local force. These ‘Uprising Forces’” as they became known, were similar to the ALP but were funded by the Afghan intelligence service and had no clear basis in Afghan law. Despite this, they have expanded over the years. Since the Islamic State established a branch in eastern Afghanistan, at least two thousand local Uprising Forces, like those pictured below in Nangrahar, have been mobilized as part of community resistance efforts.

By the time this project commenced in 2016, the ALP as a whole appeared to come closer to what its critics had feared than to what its proponents had hoped. It had a long record of ALP units engaging in human rights abuses, igniting local conflict, and furthering criminality and factional interests. According to SOF’s own assessment (as reported in a 2013 review), two-thirds of the ALP sites had failed to produce the desired security gains, and in one-third of the districts the force had been detrimental, “causing more harm than good to the counterinsurgency.”

For all the critiques, however, there was also some strong counter-evidence. Local communities continued to demand local force protection. International military credited ALP with holding the line despite expanding Taleban influence. ALP like those pictured below in Helmand’s Nad Ali District fiercely defended their community, with only little support and backup. Moreover, a case study of how the Taleban dealt with local forces in Ghazni, Zabul and Kandahar provinces suggested that local forces do indeed pose a potent counter-insurgency threat. The Taleban targeted ALP and Uprising Forces more aggressively than international or other Afghan fighters because local forces knew the local Taleban, knew their infiltration and attack routes, and could leverage community support.

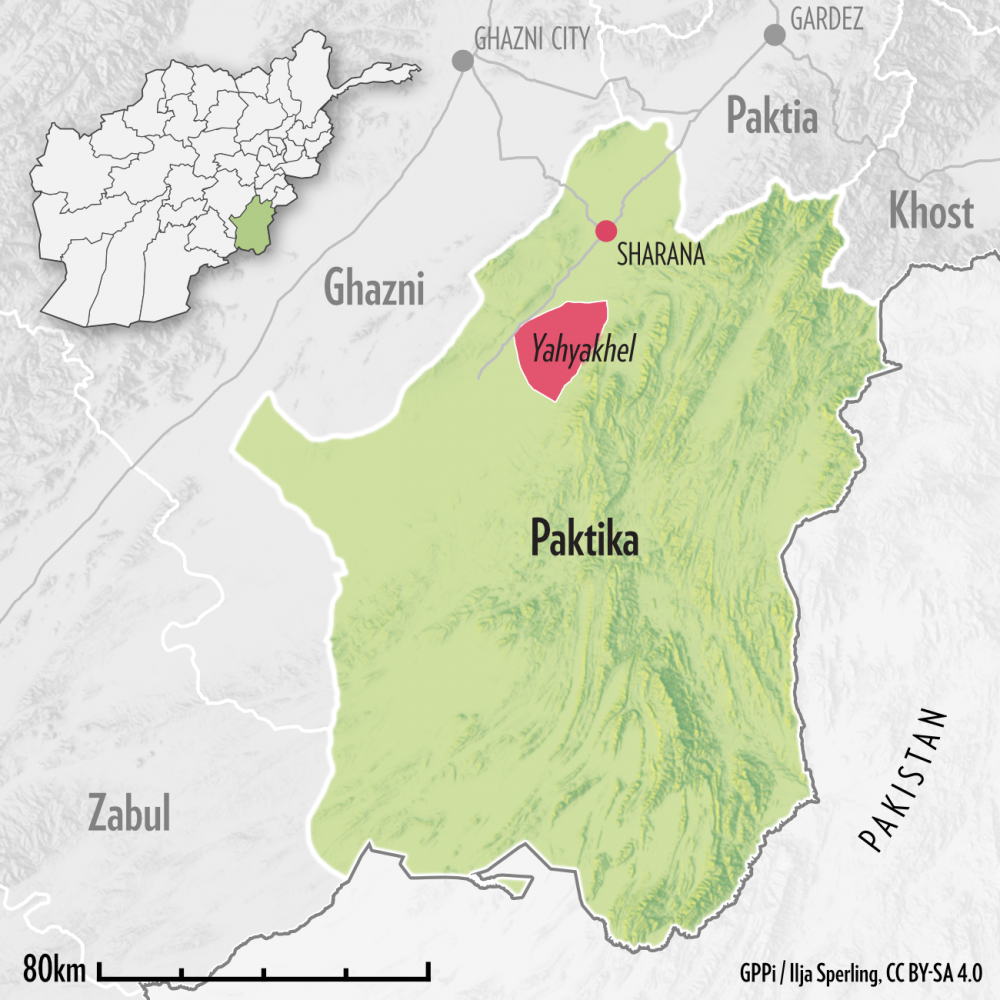

Given such mixed reviews, GPPi and AAN tried to identify where the better and worse ALP had manifested, and to pinpoint the factors behind that. There were larger regional and provincial trends, with the worst performing ALP in the north and those reputed to be better (both in terms of providing stability and not abusing the population) in tribal areas in the southeast and in Kunar province. These larger geographic trends were partly explained by demographic factors as well as by how each region’s particular conflict trajectories and traditions had shaped community structures and political dynamics. However, local dynamics were also important, as illustrated by our case studies in Andar in Ghazni province and in Yahyakhel in Paktika province.

Where there was a history of local conflict and community divisions, strong factional or commander networks, or hasty mobilization and inattention to these dynamics, ALP forces tended to contribute to, rather than reduce, local conflict and violence. In Andar, in Ghazni, inattention to local dynamics and over-eager funding of local mobilization added fuel to existing intra-tribal and inter-factional conflicts. The fighting that ensued divided the community. The district quickly went from symbolizing Taleban resistance – the Andar Uprising, as it was known – to standing for a particularly bloody, internecine form of violence.

By contrast, Yahyakhel district of Paktika province, just over the border from Andar, offered a ‘best-case’ scenario. It enjoyed a relatively conflict-free history as well as continuouslyl strong and intact local tribal structures. When a disrespectful local Taleban commander tipped the community against the Taleban, Yahyakhel was ready for counter-mobilization. Even more remarkably, local elders were given the lead and selected a force with a balanced, inter-tribal makeup that has both protected the community and prevented Taleban incursions since 2011.

A New Force and New Reintegration Demands

In the fall of 2017, Afghan and US officials decided to pilot a new local force model, which would be under the Afghan National Army and known as the ANA Territorial Force (ANA-TF). The ANA-TF was partly a cost-saving measure: each ANA-TF was estimated to cost 45 percent less than regular ANA companies. But the new force was also partly inspired and informed by the ALP. Positive cases like in Yahyakhel suggested that the model could work, but only if the pitfalls and mistakes that had manifested in places like Takhar and Andar could be avoided.

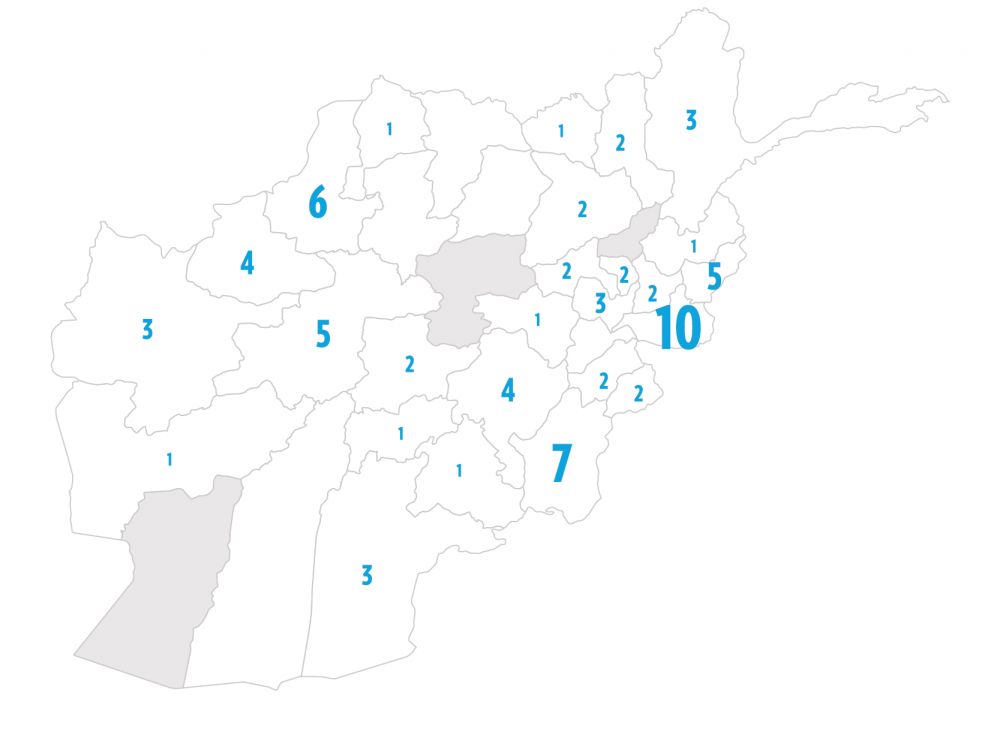

Those behind the ANA-TF emphasized avoiding the ALP’s mistakes through a slower pace of mobilization and more safeguards to improve institutional control and prevent political interference. The verdict is still out on whether such measures will work. So far, there has been more emphasis on rules and restrictions, but there are still ample examples of poor recruitment, vetting and political interference. By December 2019, there were 81 ANA-TF units trained and mobilized in 26 provinces, as illustrated by the map below.

As a result of these multiple different strands of mobilization, three different local forces are now active in Afghanistan: the ALP, the Uprising Forces, and the ANA-TF. Each belongs to a different institutional master. Yet the future of local forces is unclear, and peace talks may be shifting both the nature of and demands on local force mobilization. The ALP is set to be defunded in September 2020, with no clear demobilization or transition plan for these forces in place. The Uprising Forces under the NDS appeared set to continue, but without a clear legal basis or sustainable funding source. Some proposed transitioning the ALP or Uprising Forces into the ANA-TF or other ANSF, but so far this has not happened; many local forces would not meet the age, literacy or other standards necessary to integrate them into other Afghan forces. Moreover, some have mooted using the ANA-TF as a reintegration vehicle for Taleban fighters should peace talks succeed. This would put the approximately 20,000 to 25,000 pro-government fighters associated with local forces in competition with reconciled Taleban fighters for limited local force positions. It also might make local force selection and composition more a function of political deals in Kabul than of local community preferences – a recipe that has proved disastrous in the last decade of local force mobilization.

The still unanswered question of what a responsible demobilization of the ALP might look like underlines one last, larger risk of local force initiatives: Even if care is taken in the initial mobilization and design phase, the locations selected actually reflect communities preferences for having local forces, and these are likely to do better than outside forces, what happens to them in the endgame once the initial attention and funding for them has decreased? Although DDR has certainly been tried at multiple points in Afghanistan’s recent history, this has involved re-hatting forces as much as actually standing them down. The result can be seen in the riven landscape of many Afghan communities. Given this history and environment, the major challenge on the horizon might not be how to build better local forces, but how to finally answer the unmet challenge from 2001: that of rationalizing and standing down the many varieties of armed forces that already exist in Afghanistan.

* Data attribution: All maps in this photo essay and the underlying report were produced using Afghanistan Vector Data by Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX, managed by OCHA and licensed under CC BY 4.0). In addition, the case study maps were produced using elevation data from NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM v3, Public Domain).

For more information about our three-year project on local, hybrid and sub-state forces in Afghanistan and Iraq, visit the project home page.