Beyond Fighting Firebrands with Firebrands: How Germany Should Deal With Erdogan

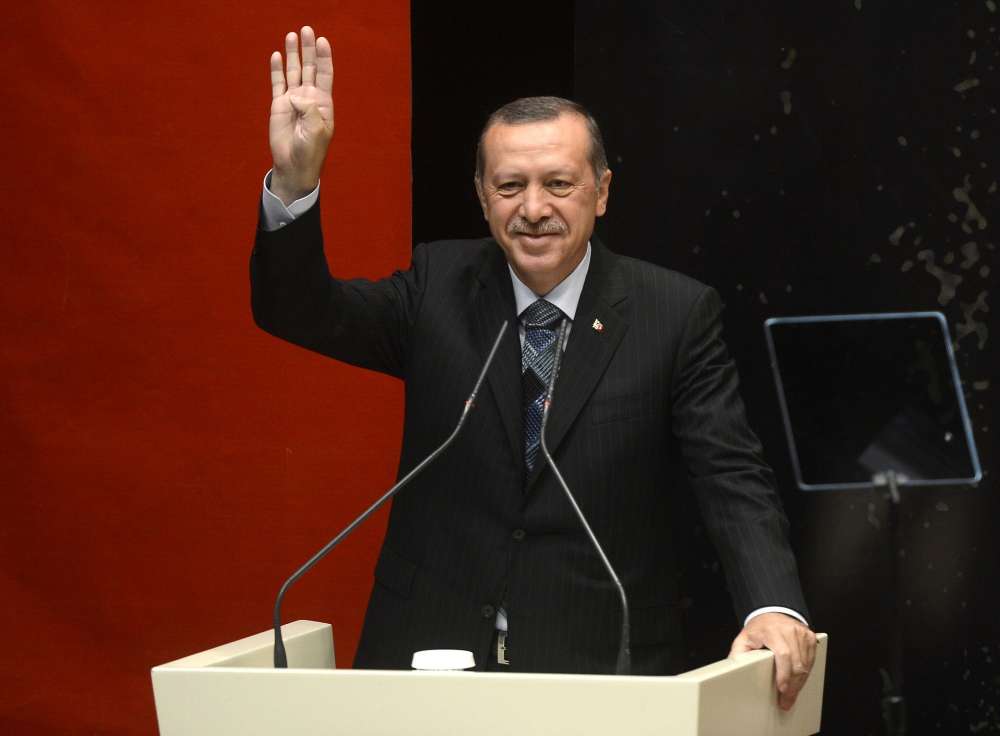

Turkey and the EU are brandishing their knives in the run-up to the Turkish referendum. Ahead of the April 16 plebiscite, in which Erdogan hopes to pass sweeping constitutional reforms to cement his authoritarian rule, he has taken to rallying abroad. To secure the vote, he is complementing his domestic clampdown with continued rhetorical escalation vis-à-vis Europe, in particular Germany. Even after cancelling his campaign events in Germany, Erdogan has continued to peddle conspiracy theories and make crude accusations, such as likening the German chancellor’s methods to those of the Nazis. Such insinuations provoke members of both the German left and right. Their solution: shut the door on Turkey and on Turkish-Germans at home.

On the left, Sevim Dagdelen has demanded an end to EU-Turkey accession talks, a withdrawal of German soldiers from Turkish soil, and a ban on all weapons exports. “No weapons, no cent, no soldiers for a dictatorship” – this is the MP’s slogan. The right echoes these proposals. Rudolf Adam, the former deputy head of the German intelligence service (BND), has referred to Turkish-German dual citizens as potential “fifth columnists.” And with a view to the 2017 federal elections, some members of Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union have shown nostalgia for their 1998 – 1999 campaign against dual citizenship, the last big show of ethno-cultural nationalism before the Merkel era.

As gripping as this public duel may be, it is ultimately counterproductive. Germany stands to lose more than it would gain from shutting the door on Turkey. For starters, Turkey is of enormous political importance in the crisis-riddled Middle East. Second, if Germany closes off the channels for dialogue to Europe, Erdogan would be pushed further into the arms of autocracrats like Putin.

It is also damaging to vilify the three million German-Turks in Germany as fifth-columnists, or to propose undoing their dual citizenship. It is precisely because some German-Turks feel like second-class citizens that Erdogan’s propaganda and promises of solidarity are appealing. Instead of fanning these flames, German politicians should strive to improve communication with German-Turks, especially with those who feel alienated.

Rather than imitate Erdogan’s approach, German government representatives need to calmly and confidently reject conspiracy theories, call out Turkish abuses of human rights – such as the large-scale imprisonment of journalists and opposition politicians and the persecution of alleged and real “Gülenists” – and criticize Ankara’s relapse into a catastrophic Kurdish policy. Merkel has been setting the example in recent months. Other politicians in the governing coalition have pursued similar approaches. Minister of State Michael Roth has talked of the need for “self-confidence,” while Niels Annen, the SPD spokesman of foreign affairs, has encouraged Klartext (straight talk).

BND boss Bruno Kahl has been exemplary in dealing with the Turkey question. In an interview with Der Spiegel, Kahl said that he was “not convinced” of the theory that Gülen masterminded last year’s attempted coup. He asserted that the purge that followed “would have happened in any case, although perhaps not with the same depth and radicalism. The coup was probably only a welcome pretext.”

At the same time, Germany must tackle Turkish espionage on its home soil by applying the full severity of the law, especially if religious or non-profit associations are used for this purpose. The Austrian politician Peter Pilz has already made a point of advancing the public debate by exposing Erdogan’s influencing mechanisms in Europe. This is urgently needed in Germany too.

If, as he has threatened to do, Erdogan holds a referendum on the question of continued EU accession talks, this could be an opportunity to put EU-Turkey relations on a more realistic track. Also, depending on the referendum results later this April, Erdogan may also tone down his rhetoric against Europe and Germany. There is no guarantee of this, but he needs economic stability to bolster his popularity.

The economic situation in Turkey is precarious (not least as a result of Erdogan’s policy). This gives Germany and the EU a certain leverage in negotiations with the Turkish government, which is heavily dependent on EU trade. German Finance Minister Schäuble has demonstrated how this leverage can be used. Such a policy of calm and confident Klartext may well be regarded as little more than “appeasement” by firebrands like Dagdelen – but this approach serves Germany far better than burning all bridges.

…

This is the English translation of a commentary that appeared in Tagesspiegel Causa on April 7, 2017.

Translation: Ana Lankes