Outcome Neutral?

The Limits of Third-Party Mediation in Ending the War Against Ukraine

Since the election of Donald Trump for a second term, public discourse in Europe about a negotiated settlement between Russia and Ukraine has increasingly focused on the bilateral dynamics between Russia and the US and their respective presidents. However, although less pompous than those of Trump and Vladimir Putin, there have already been numerous attempts to create communication channels between conflict parties since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. So far, none of these efforts have succeeded in ending the war.

What is more, debates among political elites in Germany and the EU about the best way to overcome this negotiation puzzle tend to be underpinned by several misconceptions, including the popular but empirically wrong1 notion that “all wars end at the negotiation table,” or by a false, binary understanding of fighting and battlefield developments as separate from negotiated talks.2 In fact, the interplay between war and diplomacy is complex3 and in the case of Ukraine, “it will be the course of the war itself that determines whether ceasefire negotiations are likely or possible.”4 Behind the renewed diplomatic engagement between the US and Russia, German and EU actors continue to struggle with the key questions: What kind of diplomatic negotiations constitute a reasonable approach to ending this war? And who should take part in them?

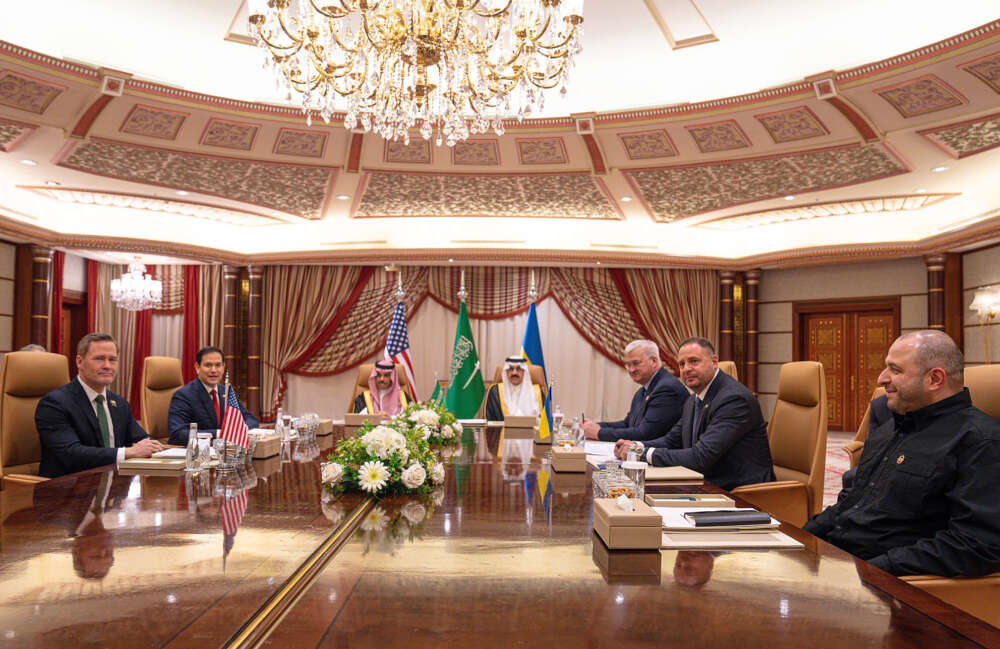

Some global leaders have suggested that an impartial third-party mediator is crucial to the success of negotiations. Proponents of this position cite examples such as the Cold War, when non-aligned states offered their “good offices”5 to mediate between the great powers on various occasions. Their impartiality and a certain “outcome neutrality”6 were seen as an advantage. In the Russia/Ukraine context, several third-party actors — namely Brazil, China, India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Turkey — have been cited as potential mediators and have already engaged in various ways in diplomatic initiatives since the start of the war.7

Drawing on 27 interviews with officials and researchers in and from these six countries, as well as 14 background conversations with other experts, this policy paper explores the role of these states in negotiations around the war against Ukraine. It offers an in-depth exploration of the positioning, motivations, calculations and actions of third-party actors in mediating between Russia and Ukraine by answering: How and why have these third-party actors engaged in mediation efforts in the Russia-Ukraine war? And, despite the limitations of these efforts, can they make a difference in the future? It finds that these countries are highly unlikely to be driving forces of any successful negotiation efforts, as they have been mostly motivated by status concerns in a changing global order and only engaged with the war when it came with benefits and without any risks to their international reputation. However, third-party actors can play a role in the pragmatic facilitation of incremental steps towards peace.

This brief shows that many countries see the war in the context of a struggle for a new, potentially more just, international order characterized by a decline of American and European power, in which Russia is an indispensable player. In this context, the rationale for most of the third-party actors to engage with Russia and Ukraine includes partially overlapping considerations related to their economic interests, concerns about their status on the global stage, and the personal ambitions of their leaders. Some are driven by a desire to be seen as promoting global peace or choose to engage simply because they are asked by other leaders to mediate or host. Their involvement tends to be shaped by their geopolitical positioning as well as a willingness (or lack thereof ) to take risks. For this reason, these findings are relevant to European diplomacy beyond Ukraine. At the end of this brief, the findings are translated into five concrete recommendations for European leaders.

Key Takeaways

- Most potential third-party negotiators – namely Brazil, China, India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Turkey – oppose Russia’s war on Ukraine but also see it as an opportunity to increase their status in a changing world order.

- European leaders should be pragmatic about their mostly transactional motivations. While they can learn from third-party actors to think about negotiations in incremental steps, hopes for any of them to unlock an “easy” solution to the war are misplaced.

- Most of these actors prefer to engage in lower-stake activities like hosting talks or passing messages that still leverage their third-party status.

- Some third-party actors should be approached not only as partners but also as potential spoilers of diplomatic efforts.

- European decision-makers should engage with justified criticisms of Western hypocrisy by third-party actors, while also working to actively counter Russian narratives.