DIE ZEIT: Mr. Benner, in a guest article for the Handelsblatt, you called for the next German government to work with France and the UK on joint European nuclear deterrence. Why should they do that?

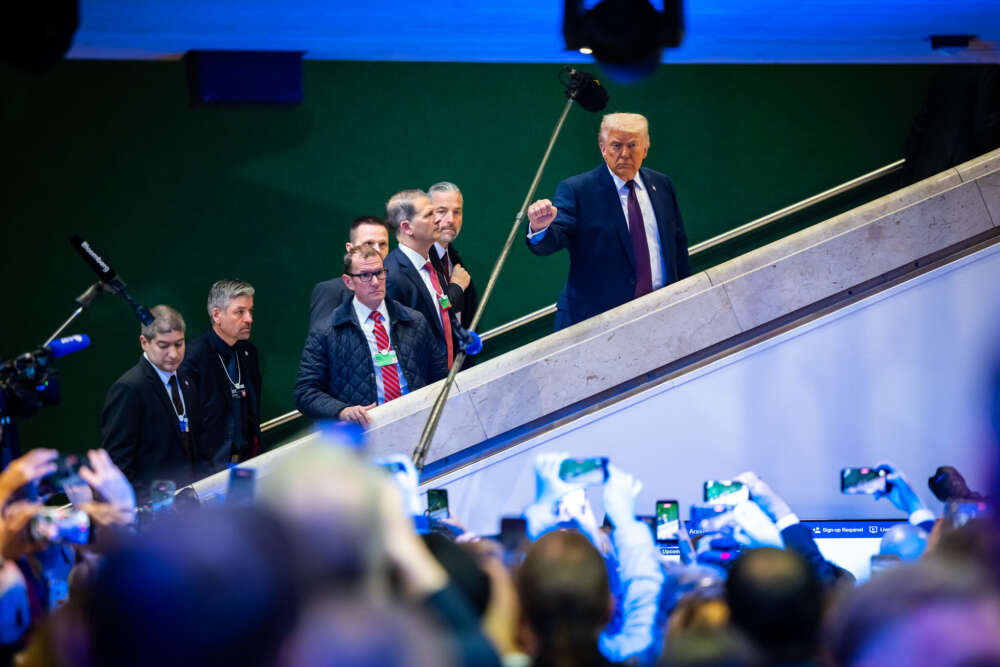

Thorsten Benner: Politics begins with a clear-eyed view of reality. And the reality is that nuclear power Russia is using nuclear threats to pursue its imperial ambitions against non-nuclear states — including Ukraine. Additionally, there is a very real risk that the US, under Donald Trump, might not only withdraw its conventional security guarantees for Europe but also its nuclear umbrella. That’s why we need to establish nuclear sharing on a European level instead of relying solely on the US.

ZEIT: Mr. Stegner, do we need the bomb?

Ralf Stegner: There are around 13,000 nuclear warheads in the arsenals of nuclear powers worldwide. That’s why I say: The last thing we need is more nuclear armament. On the contrary, we need to work on reducing the number of nuclear weapons — which is already difficult enough. The ability to destroy the world has multiplied since 1945. That’s why I believe this is a dead-end road. We need to move away from nuclear weapons, not discuss acquiring new ones — especially not arming Germany with nuclear weapons.

Benner: I, too, would prefer to live in a world without nuclear weapons. But that’s completely unrealistic. No one is willing to engage in disarmament at the moment. If we fail to establish a European nuclear deterrent independent of the US, we make ourselves vulnerable to blackmail. If we don’t want to submit to the Kremlin and other potentially hostile nuclear powers like Iran, we have no choice but to invest in a shared European deterrent.

Stegner: You’re talking as if we are defenseless. But we’re not. On the contrary — the Baltic region and NATO have been strengthened by the accession of Finland and Sweden. That was something Russia didn’t anticipate. Putin has still not achieved his war goals in Ukraine, despite significant sacrifices within his own population. The idea that he could march his troops into Berlin tomorrow if he wanted to is completely unrealistic. We must be able to defend ourselves, but that doesn’t mean we should enter an arms race. That would drain resources that are needed to address real problems: hunger, civil wars, environmental destruction and refugee crises. The world is not suffering from a lack of weapons.

Benner: I find it ironic that voices like yours, which have always been highly critical of the US and NATO, now place such blind faith in them. Besides, what if Putin is in Vilnius tomorrow? There’s already a German brigade stationed in Lithuania — if something happens, we’re in a war. I’m not as confident as you that we’re fully prepared for that. More importantly, we need to consider how we organize deterrence if the US no longer provides it. Ask the South Koreans — they are terrified that Trump will strike a deal with North Korea over their heads. They openly talk about pursuing a nuclear option if that happens. The same goes for Turkey, Saudi Arabia and other nations.

Stegner: I’m certainly no fan of Donald Trump, but I’m not as pessimistic as you. The US has interests — it’s not in their interest to let Russia conquer Europe. We are also too economically important for that. And actually, it’s the opposite: we will lose relevance as an economic power if we pour more and more resources into armament instead of infrastructure, future technologies and modernizing our country. I think Germans have a neurotic relationship with the US: we are constantly afraid that they will turn away from Europe and toward Asia, and that the nuclear umbrella will disappear. This debate is not new — it has existed for years. So far, the umbrella is still there.

Benner: I hope you’re right, but I wouldn’t be so optimistic. Friedrich Merz put it well: we cannot be sure that NATO is stable. Trump repeatedly emphasizes that there is an ocean between Europe and the US — he says that for a reason. He believes the US doesn’t depend on Europe. We are dealing with a US government that seems largely indifferent to Europe’s fate.

Stegner: Trump talks a lot. But he is not America. There are the states, a vigilant civil society and the courts. American democracy has always been more robust than ours. It will survive the Trump years as well, even though it is a tough ordeal.

Benner: Nevertheless, we need a Plan B. I’m not saying that the withdrawal of the US will definitely happen, but it would be grossly irresponsible not to be prepared for it. There are two nuclear powers in Europe: France and the UK. We should try to organize nuclear sharing at the European level — not just with Germany, but also with Poland, Italy, and perhaps even Spain.

ZEIT: Political scientist Herfried Münkler has suggested a “joint nuclear suitcase” that would rotate between major EU countries. Is that your model?

Benner: No, that’s pure fantasy — it won’t happen.

ZEIT: Who would order a nuclear strike in an emergency? Ursula von der Leyen?

Benner: The final decision would remain with the nuclear powers, meaning the UK and France. That’s also how it works with the US. However, Germany would be involved in the decision-making process through nuclear sharing. There would be a Nuclear Planning Group made up of France, the UK, Germany, Poland, Italy, perhaps Spain, with the remaining EU member states represented by the European Council president or the EU foreign affairs chief. This would be a realistic solution. And of course, we would have to contribute financially to deterrence. The alternative would be a German bomb, and I think we can all agree that, for both political and practical reasons, that is not a desirable option at the moment.

Stegner: I believe a nuclear war would only be started by madmen. The logic of deterrence is simple: “whoever shoots first, dies second.” And whatever you think of Putin — I don’t believe he is insane. Also, it’s not just about Russia. China has no interest in nuclear escalation. We should engage with the Chinese instead of pursuing nuclear armament in Europe. I worry that diplomacy is increasingly equated with submission and appeasement. We should talk more about collective security and economic cooperation rather than escalating global conflicts. My generation is the first in Germany to grow up in prosperity and peace. If we only focus on military logic, it could also be the last. We cannot allow that to happen!

Benner: We agree on the need for disarmament initiatives. Germany has pushed for that in recent years, but major powers haven’t listened. The blame lies with all sides: the US under Trump, Russia breaking numerous treaties and China rapidly expanding its nuclear arsenal. Russia’s goal is to subjugate Europe under its hegemonic ambitions. Is it escalation if we try to compensate for the loss of the US security guarantee? I don’t think so. Instead, it is a clear signal against Moscow’s demands for submission. And it would also show the Americans that we understand the seriousness of the situation.

ZEIT: Mr. Stegner, Friedrich Merz has also advocated for a European nuclear deterrent. With potential coalition negotiations ahead, do you think the CDU and SPD could reach an agreement on this issue?

Stegner: I can’t imagine the Social Democrats agreeing to such a plan. That would take us back to Franz Josef Strauß and the 1950s. One thing is clear: we need to strengthen our alliances and defense capabilities. We’ve done that with the special defense fund for the Bundeswehr. We’re increasing our presence in Lithuania along NATO’s eastern flank. We should also work closely with France and the UK. But we must also recognize the political reality in Europe. Italy is governed by Giorgia Meloni, a post-fascist; Marine Le Pen is a major force in France; Viktor Orbán rules Hungary. Nationalism and right-wing populism are spreading — those are the real problems.

Benner: Indeed you could argue that if, in a few years, Le Pen governs France and Nigel Farage leads the UK, then the idea of joint deterrence is dead. But if you are certain about this already now, the only alternative would be to go for a German bomb today. For sure, Germany should aspire to maintain nuclear latency, that means the necessary scientific and technological capabilities for a nuclear program. For now, though, we should pursue a European option, even if it comes with uncertainties. I also wouldn’t rule out reaching an agreement with a France under Le Pen to maintain a common defense arrangement.

Stegner: The idea that agreements with far-right leaders could be in our interest is beyond my imagination. I trust in the stability of American democracy more than that. I was even more shocked by what happened in the German Bundestag four weeks ago — led by a conservative politician who is positioning himself to become Chancellor and who collaborated with the AfD there.

Benner: Are you seriously equating a tactical misstep by Friedrich Merz in the Bundestag with the greatest crisis in the Western alliance since World War II?

Stegner: Cooperating with right-wing extremists is not just a tactical misstep. This is also about the stability of democracy itself. After the Great Depression, the Americans did not succumb to fascism — they have no tradition of authoritarian rule. That is different in some European countries, and that worries me.

Benner: I agree — the greatest threat to our democracy comes from within. But we cannot simply ignore the potential loss of the American security guarantee and a collapse of the transatlantic alliance.

Stegner: But we also shouldn’t start politically hyperventilating.

This debate was originally published in German in ZEIT ONLINE on February 26, 2025.