Europe's Moment to Get on the Front Foot on De-Risking from China

With less than two weeks left until Donald Trump takes office as U.S. President again, Europeans are bracing for impact. The threat of blanket tariffs and weakened security commitments is top of mind. Tactical preparations for possible retaliation on the trade front are important, but not enough: European leaders should actively seek a deal with Trump on trade and economic security.

Any such deal will likely be messy, with no single aspect holding the key to success, despite Trump’s focus on more European oil and gas purchases in a recent social media post. That makes it all the more critical to use the limited time remaining to get on the front foot on those issues where pursuing enlightened self-interest can simultaneously improve the terms of engagement. De-risking from China is a critical topic in this regard.

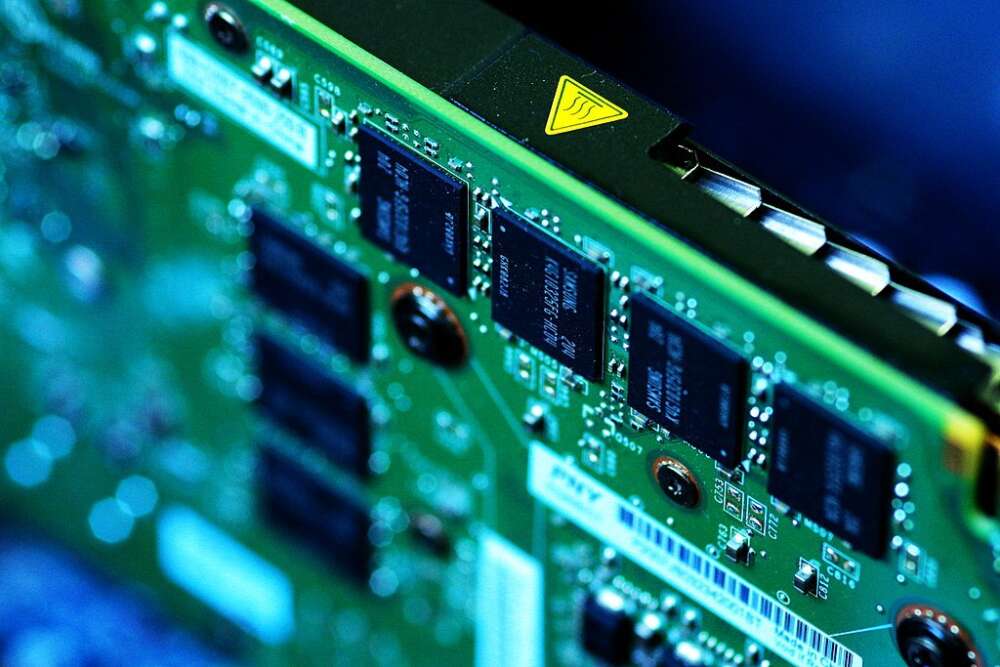

More importantly, the European embrace of a de-risking agenda, championed by Commission President Von der Leyen, was never a matter of doing the US a favor. Rather, it reflected on an overdue reassessment of Europe’s own vital interests in managing relations with a China increasingly authoritarian at home and aggressive on the international stage. The need to address concentrated supply chain dependencies and vulnerabilities to espionage and sabotage via critical infrastructure are now widely acknowledged in the abstract, but faster progress is needed in practice. More fundamentally, Europeans never truly got on board regarding the centerpiece of what the Biden administration also referred to as de-risking, namely its effort to contain China’s military modernization by restricting access to cutting-edge technologies.

Given the evolution of Beijing’s posture and actions over the past decade (most notably regarding Taiwan), deterring aggression in the Indo-Pacific by making it less likely to succeed simply on account of the military balance of forces should be an obvious European priority as well. The notion that the same degree of deterrence could be accomplished through the threat of sanctions in the event of an actual attack strains credibility, particularly as long as Europe remains so vulnerable to Chinese economic coercion itself. A lesson that Europe should have learned the hard way from Vladimir Putin in February 2022.

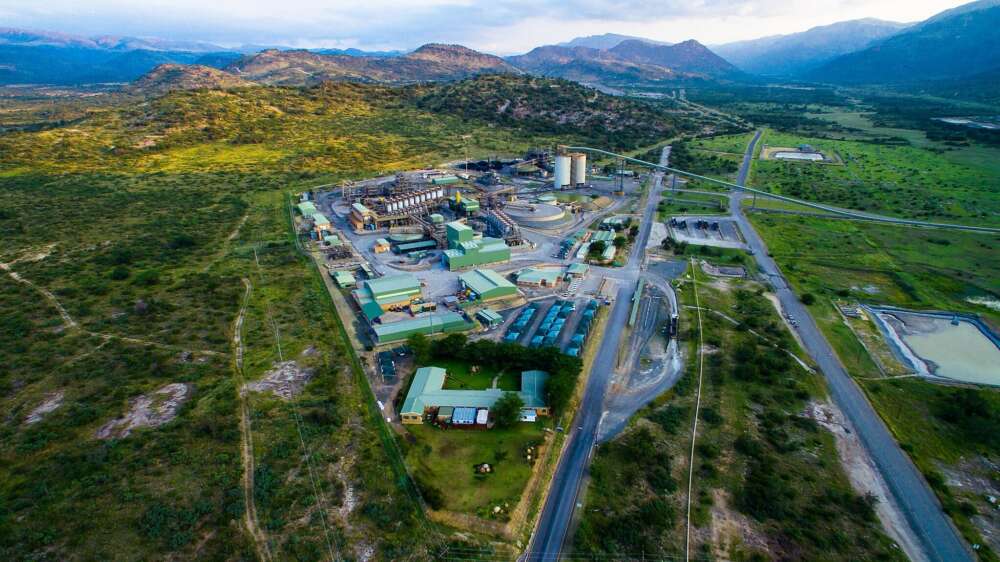

Despite widespread (and often justified) self-flagellation on the lack of European technology leadership, Europeans also have options available that really matter. For example, the continent is home to firms that possess unique capabilities in building the most advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment. The Netherlands eventually adopted reinforced export controls affecting Dutch-based key firm ASML after intense US pressure, but where more could be done to hinder Chinese efforts to replicate these capabilities. Likewise, thanks to its large single market, EU regulation will play a pivotal role in whether China can remain a global production hub for hardware and software for connected vehicles, following the adoption of US restrictions in this area. While primarily motivated by concerns about espionage and sabotage, measures would likely have broader ripple effects on the speed of commercial development of autonomous vehicles in China, also a technology with obvious military applications. This list could be continued.

Europe should long have taken action in these areas purely on its own account, rather than waiting to be pressured by the Biden administration. Its leaders should hardly expect gratitude and congratulations from the Trump administration if they do so now. But what they can credibly explain to Trump is that these measures are economically costly, and that they will not be able to pursue them if they are embroiled in a trade war with the US and on high alert on national security threats from Day 1 of his Presidency. While the new administration will likely be less coherent on China than Biden’s was —with Elon Musk’s business interests making for a particularly unpredictable factor— such an unnecessary distraction from dealing the widely agreed pacing challenge of US national security would seem like a hard sell even among the most Eurosceptic parts of the MAGA coalition.

If an opening gambit on de-risking along these lines succeeds as part of a broader initial deal, determined and sustained follow-though will be essential. That does not mean uncritical endorsement of any technology restriction that the Trump administration may come up with —Europeans should certainly keep a critical eye on effectiveness, unintended consequences, and unnecessary collateral economic damage. But their approach should be guided by a much clearer commitment to containing China’s military modernization than in the past, even where this comes with substantial economic costs.

At the same time, European policymakers should double down on their efforts to invigorate innovation in emerging technologies, seeking cooperation with partners in the G7 and beyond whenever possible. The immediate focus regarding the Trump administration, for sure, needs to be on preventing the worst. A world marked by intense rivalry between two superpowers will, in all likelihood, be more economically strained and dangerous than the one of the past three decades. However, it also creates space for collaboration and division of labor among allies in maintaining a technological edge. Europe should do what it can to steer the conversation in this direction.

This commentary was originally published by Agenda Pública on January 9, 2025.