Protecting Civilians Through UN Peace Operations

Under the flag of the United Nations, more than 125,000 civilian experts, police officers and soldiers are currently deployed in 16 missions worldwide to give peacebuilding efforts a better chance of success. In most cases, these efforts take years. Even as politicians and military leaders negotiate, fighting and assaults against civilians continue. Given this context, the UN Security Council as well as the people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and the Central African Republic expect UN peacekeeping operations to do their best to reduce the suffering of civilians and to protect as many of them as possible. According to the mandates of the Security Council, these are in fact the most important objectives of the vast majority of UN peacekeeping missions. Prioritizing civilian protection until it sits at the core of peacekeeping operations is a painful learning process that remains far from complete.

Difficult Learning Process

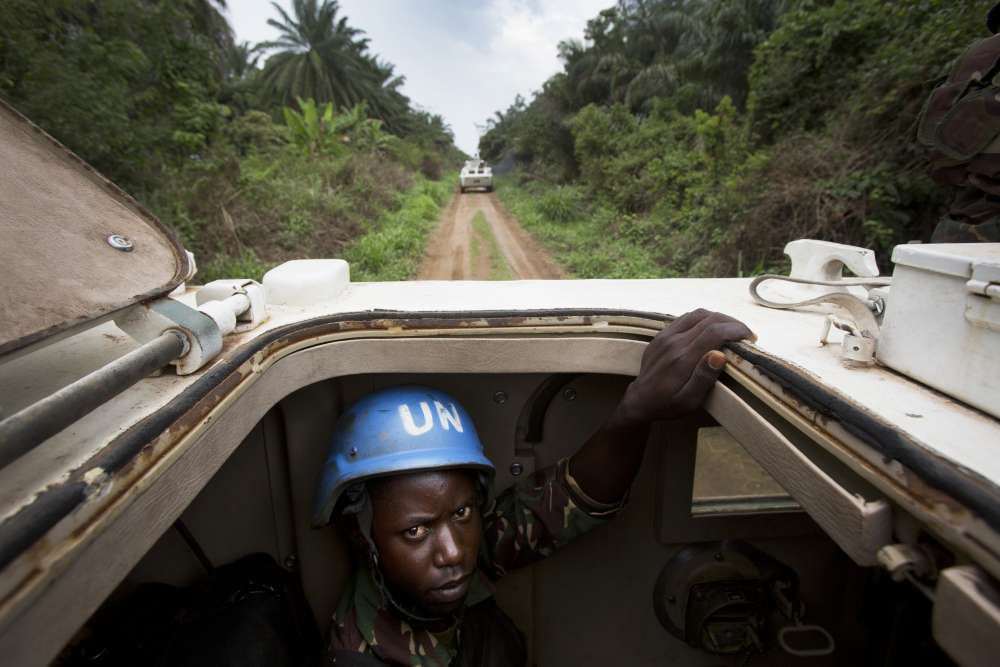

Since the early 1990s, the tasks of UN peacekeeping missions have significantly expanded alongside the increasing international awareness of intrastate conflicts. These missions formerly comprised just hundreds of UN military observers wearing their iconic blue helmets – a familiar sight during the Cold War. Now they are complex, sprawling organizations with thousands of political experts, police officers and soldiers who cover a wide range of tasks: political analysis, institution building, the monitoring of ceasefires, the protection of human rights and the use of military force to protect civilians.

The double failure of the UN and national governments to adequately respond to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica plunged the peacekeeping system into a crisis of credibility. The UN overcame this crisis only at the end of the decade by, among other strategies, committing itself to the improvement of civilian protection in armed conflicts. From the outset, this constituted a balancing act between inactivity and excessive demands. Blue helmets are not supposed to be a global SWAT team that uses superior force to suppress violence against civilians; this is neither feasible nor politically desirable. At the same time, however, peacekeepers learned from the UN failures of the 1990s that they must not simply stand by as massacres that they could have prevented, even by military force, unfold before their eyes. In 1999 the UN Security Council authorized, for the first time, peacekeeping forces in Sierra Leone “to afford protection to civilians under imminent threat of physical violence” within their “capabilities and areas of deployment.”

The following year, an expert commission led by Algerian diplomat Lakhdar Brahimi urged UN missions to hold fast to the goal of protecting civilians, despite the failures of past attempts. In fact, missions must be equipped adequately and the rules of engagement adapted accordingly to “allow ripostes sufficient to silence a source of deadly fire that is directed at United Nations troops or at the people they are charged to protect.”

The peacekeeping missions in Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan in the 2000s barely lived up to the demands of the Brahimi report. While the Security Council and member states set high normative standards for themselves (including “the responsibility to protect”), the actual means deployed and the risk tolerance of troop-contributing countries fell substantially short of these self-imposed expectations. As a result of deficiencies in planning and management, commanders on the ground often lacked clear guidance about when the use of military force for protection purposes was justified. In the absence of guidance, most commanders ended up hiding behind maximum caution. For instance, the former UN mission commander in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indian general Bipin Rawat, stated in 2008, “We have very strict rules against collateral damage. If I kill one civilian, there is no one to hold my hand.”

Instead of dealing with these critical but politically sensitive issues, the UN secretariat’s further conceptual specification in subsequent years has confined itself to emphasizing a mission’s diverse civilian resources dedicated to civilian protection. According to this work, a mission’s responsibilities involve not only military patrols and the use of force against “imminent threats,” but also the demobilization and reintegration of ex-combatants, the training of capable security forces, demining and destruction of weapon stockpiles, the protection of children and the prevention of sexual violence. But the main questions concerning the benefits and limitations of military force remain unanswered.

Protection by Military Force

Peacekeeping missions like those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or in Sudan’s Darfur region are deployed amidst armed groups that operate in shifting alliances and terrorize the civilian population, frequently with support from government forces or neighboring states. In this context, the effective protection of civilians in conflict areas is often impossible without the use of force. Nevertheless, military force has achieved only limited success thus far.

The controversy over the use of force touches upon traditional, core principles of UN peacekeeping that remain valid to this day: consent of the parties, impartiality and non-use of force except in self-defense or in defense of the mandate. The military fight against any “party” (regardless of its diplomatic classification as a conflict party or not) limits a mission’s impartiality and may harm its freedom of action and movement in the contexts of political mediation, human rights monitoring and institution building. Meanwhile, the local population is often ambivalent: while most victims of armed conflicts appreciate the fight against violent rebel groups, others hold the UN responsible for civilian fatalities that are incurred as a result of UN military operations.

The balance ultimately struck by a peacekeeping mission depends critically on the contingent commanders, the senior mission leaders and the rules of engagement of troop-contributing governments. For example, the UN mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) conducted offensive operations as early as 2005. The mission, armed with combat helicopters, destroyed weapon caches and supported the Congolese forces in their fight against rebel groups. Such operations often lead, at the very least, to a short-term decline in attacks on civilians.

Despite those operations, incidents in which peacekeeping troops have failed to intervene in nearby massacres have cropped up time and again. In November 2008 approximately 150 people died in Kiwanja, most of them by the hands of the Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP) rebels, one of the largest armed groups in the Congo at the time. A UN base with 120 soldiers was less than one kilometer away from the scene of the massacre. But they did not intervene because they had only a few armored vehicles and were concentrating their capacities on the protection of humanitarian aid workers and internally displaced persons who had fled to the UN base.

In 2012 MONUSCO was strongly criticized yet again, having failed to prevent a rebel invasion of Goma, a provincial capital in the Democratic Republic of Congo, by the armed group M23. Six months later, the Security Council took action, not least to avoid a unilateral military intervention by the Southern African Development Community. South Africa, Tanzania and Malawi contributed 3,000 men to the establishment of a Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), equipped with artillery, combat helicopters and surveillance drones. The Security Council explicitly authorized the brigade to “neutralize” armed groups that threaten civilians. Under the leadership of Martin Kobler and Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz – the German head of mission and the Brazilian commander of MONUSCO, respectively – the brigade successfully evicted M23 from the mountains of Goma.

The FIB has since been regarded as a new model of offensive peacekeeping. But the Congolese case also reveals the risks and challenges of this approach. As the FIB only takes action in conjunction with official Congolese government forces, the UN mission has de facto given up its principle of impartiality by supporting the Congolese government in its fight against other conflict parties. Congolese forces, moreover, have also been responsible for serious violations of human rights, despite long-lasting international training and support. As a result, the UN mission introduced a policy on “human rights due diligence.” Subsequently, all other UN peacekeeping missions adopted the policy as well.

Another concern raised by the FIB is that large military offensives with artillery and combat helicopters, as used by the brigade in its 2013 fight against M23, may be effective only if rebel groups engage in conventional warfare. The M23, a group of Congolese soldiers who had deserted from the Congolese armed forces, was one such case. However, many other rebel groups in the Congo and other areas of UN peacekeeping missions operate underground, carry out single attacks on military units and local populations, and then withdraw once more.

Despite the UN’s recent willingness to authorize robust missions that carry out offensive operations against armed groups, a UN investigation in 2014 showed that military force is rarely used to protect civilians even in cases of severe threats. The reasons are many: troop-contributing countries differ in their views of what constitutes being “under imminent threat of physical violence”; troop-contributing governments want to minimize risks for their soldiers; and, for reasons of impartiality, mission leaders are often reluctant to prevent atrocious human rights violations by taking action against not only rebels, but also national armed forces, even if the mission’s mandate would allow them to do so.

Political Analysis, Conflict Management and Human Rights Work

The dispute over the role of military force should not obscure the fact that civilian instruments such as early warning, civilian conflict management and human rights work are also crucial factors in the effective protection of civilians. Neither preventive, deescalating political interventions nor military operations can be effective if missions lack necessary information on local conflict dynamics. Where are armed groups primarily active? Who supports them, and for what reasons? How do they obtain weapons and other supplies? Countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Mali are huge and have only very limited infrastructure, making it impossible even for large missions to protect all threatened communities effectively. Moreover, the military units of peacekeeping missions often lack the knowledge of regional languages and geography needed to properly communicate with the local population.

MONUSCO was a pioneering mission in this regard. The mission boasts more than 200 Community Liaison Assistants (CLAs), Congolese citizens who are posted with military units or in nearby villages. By maintaining constant communication with the local population through telephone calls or personal visits, they receive crucial information on current risks and conflict dynamics. MONUSCO was also the first peacekeeping mission to deploy drones for tactical reconnaissance in remote areas.

UN missions can use the information obtained to support local efforts in civilian conflict management. They can organize roundtable events with members of local communities, offer logistical support to convene key figures in dialogues and organize workshops with local elites to familiarize them with conflict management methods.

Furthermore, all larger and multi-dimensional peacekeeping operations have their own human rights divisions. They monitor and report on human rights violations, help victims understand their rights and urge the appropriate authorities to punish violations and implement legal reforms. However, the UN’s efforts to ensure fair trials for criminals and murderers in accordance with the rule of law sometimes encounter local resistance. For example, Cuibet in South Sudan lacks judges of sufficient qualifications who can deal with capital crimes. As a result, trials are sometimes delayed for months, increasing tensions in the local community. “Justice delayed may cause acts of revenge,” a representative of a women’s association warned at a roundtable event on the implementation of a peace agreement in June 2015. “The relatives of a murder victim may take the law in their own hands.”

Protection From the Protectors

The credibility of UN missions has suffered not only from doing too little in response to violence. Too often, blue helmets are the ones sexually exploiting or abusing civilians. For more than 10 years, the fight against sexual exploitation and abuse has been a core element of reform efforts by two UN secretary-generals.

Much progress remains to be made. The core problems persist: troop-contributing countries retain disciplinary responsibility for their military units flying the UN flag; troops enjoy immunity in their host country; and troop-contributing countries rarely initiate investigations. Even when perpetrators are convicted, victims are not informed of the outcome. Many troop-contributing countries, according to an independent study, are “reluctant to admit the misconduct of their peacekeepers, especially where such misconduct can be traced back to inadequate training, and would rather sweep allegations under the rug.” Reported allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse have declined since 2007 while the number of UN troops increased, but plateaued at a constant level of about 60 accused per year since 2012. These numbers should be viewed with caution, for many victims do not dare to report such incidents and certainly would not approach the UN mission.

The allegations of sexual abuse that emerged in April 2015 demonstrated that the need for essential changes within the UN secretariat persisted even after Kofi Annan’s reforms of 10 years prior. French soldiers of the UN-mandated Operation Sangaris, which is not a blue helmet mission under orders of the secretary-general, allegedly lured children in the Central African Republic into sexual acts in exchange for food. The reaction of the UN mission and secretariat was highly problematic, as confirmed by an independent investigation set up by Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. Information about the allegations was “passed from desk to desk, inbox to inbox, across multiple UN offices, with no one willing to take responsibility to address the serious human rights violations.” The UN officials who dealt with the allegations were primarily concerned with technical and procedural questions. In the meantime, French authorities initiated investigations, but they have yet to make any convictions. While Ban took the unprecedented step of dismissing the head of the UN mission in the Central African Republic, the highly symbolic move did not put a stop to the problem. Since then, more and more similar accusations against soldiers of the UN mission in the same country became public.

Comprehensive Political Strategies

Alan Doss, head of MONUSCO from 2007 to 2010, claims that “the use of force must be anchored in a political strategy to end armed violence.” Too often, UN missions fight only the symptoms of violence, not their root causes. In its 2015 report, the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations also emphasized the importance of political action. But what may seem like an intuitive recommendation faces serious resistance in practice: “It’s far easier for the Security Council to send peacekeepers to a trouble spot than to agree to apply pressure on political leaders whom some members of the council invariably view as allies,” argues James Traub, a long-time UN expert.

To protect civilians from massacres and persecution in war and conflict regions, all actors involved must come together – that is, the political leadership of missions on the ground, the UN Security Council and its permanent members (United States, France, Great Britain, Russia, China), the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations in New York, the UN secretary-general, various UN agencies, funds and programs, and the relevant member states, whose bilateral relations with conflict parties are particularly important.

The US is a telling example in this regard. As long as it came to Rwanda’s defense, despite its support for rebel groups in Eastern Congo, it impeded MONUSCO’s activities. Therefore, an important signal was sent to the FIB’s offensive when the US eventually froze its military aid to Rwanda in response to Rwanda’s support for M23.

The UN system has increased its efforts to incorporate the issue of human rights protection into its operating procedures. The “Human Rights up Front” initiative established by Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in 2013 has contributed to a gradual change in the organizational culture, which has so far been marked by bureaucratic silos and turf wars between its humanitarian, security and development arms. The UN has begun to attach greater importance to coordination in the areas of early warning and crisis response, and it frequently convenes relevant UN actors on the ground and in its New York headquarters to better understand the different risks and benefits perceived by their colleagues. But there is still a long way to go before a consistent policy on the protection of civilians is established at all levels of the UN.

Notwithstanding these reform efforts, the experiences of UN peacekeeping missions to protect civilians underscore the need for transparent management of expectations, clear communication with all stakeholders and an appropriate degree of humility about what the international community can do. Even in the most fragile states, large peacekeeping missions are no panacea. The presence of thousands of soldiers and well-paid civilian employees from different cultures is bound to disturb the local economy; in the worst case, it may even lead to further crimes committed against the local population. Host country institutions remain the most important actors in the prevention of violence against civilians. They cannot be released from this fundamental responsibility, no matter how well equipped or politically backed a peacekeeping mission might be.

…

The paper was originally published in German by Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte on March 4, 2016.