The Carney Doctrine Needs a Dose of Realism – and Honesty

Mark Carney’s speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos on January 20 was, by far, the best articulation to date by a Western head of government of how middle powers can navigate the current moment in world politics. And the Canadian prime minister chose his moment wisely.

For a year now, US President Donald Trump has been swinging a wrecking ball at the international order and alliances that have stood at the heart of US foreign policy for eight decades. With his open threats against NATO ally Denmark to annex Greenland, Trump’s rampage reached a grim climax from the perspective of US allies. “Enough is enough!” was the reaction not only of German Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil, but of many who were fed up with the schoolyard bully narcissism of the US president and his acolytes. Carney combined this “Enough!” with a positive agenda that shows how middle powers can band together to form a counterweight to abusive great powers, but also tackle global challenges together in new formats of cooperation. As inspiring as Carney’s middle powers doctrine sounded, however, it needs more honesty and realism.

A Rupture, Not a Transition

In many ways, Carney built on familiar ideas. Talking about “middle powers” is as Canadian as maple syrup. Canada has long prided itself on working with like-minded countries, for example by leading the Ottawa Process to ban landmines in the 1990s. Carney’s approach also recalled the more recent Alliance for Multilateralism that Germany promoted together with France and Canada during Trump’s first term.

But Carney added two important new points in his analysis. First, he spoke clearly of the world being in the midst of a “rupture,” not a “transition.” The Alliance for Multilateralism still assumed that the Trump aberration merely had to be weathered. The bet was that middle powers would stabilize the multilateral order with additional resources until, after Trump, a new US administration would once again assume its familiar leadership role. Germany, for example, significantly increased its spending on humanitarian assistance during Trump’s first term.

Carney’s diagnosis of a “rupture” made clear that, in his view, there will be no return to the status quo ante after Trump’s second term ends. That is not necessarily a deterministic assumption about the direction of US politics. Carney (like the leaders of other Western middle powers) can certainly imagine and would welcome a post-Trump administration that is less hostile to international institutions, not to mention neighbors and allies. But it’s clear that the trend that is causing the rupture is bigger than Trump.

It’s also a result of the increasingly unrestrained behavior of China and Russia. That won’t stop just because there is a more cooperation-minded US president in the White House. And middle powers are already asking whether existing institutions still work for them and adjusting their policies. A case in point is the World Trade Organization (WTO), where more European members are doubtful about whether a strict interpretation of the rules allows them to effectively guard against competition from China. Having a gigantic authoritarian state capitalist economy with non-market practices that is acting against the very spirit of the WTO in key areas is not something the institution was designed to deal with. It’s also certainly not what Western countries bargained for when they admitted China to the WTO. It is not just the US but also other Western WTO members who are re-considering to what degree the institution still works for them.

There are other examples for this. In the light of Russian sabotage operations European countries are also re-considering whether a traditional interpretation of the UNCLOS convention on the Law of the Sea hinders them from effectively dealing with attacks on critical infrastructure that take place outside territorial waters in the Baltic Sea. And faced with the renewed prospects of a Russian invasion, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Finland have announced the withdrawal from Canada’s landmark Ottaway Mine Ban Treaty.

Plus, there are ideological fellow travelers of Trump’s MAGA movement that have decided to move against international institutions. Hungary under the leadership of Victor Orbán decided to withdraw from the International Criminal Court. What’s more, this time around Western middle powers are unable and unwilling to compensate for the loss of US financial contributions to international institutions. This is because there have been significant cuts to development and humanitarian spending in most Western countries. Budgets have declined sharply for example in the United Kingdom and Germany. That is a trend unlikely to be reversed given the increasing fiscal constraints across G7 countries and the need for increasing military spending. Carney’s assessment that there will be no return to the status quo ante therefore makes a lot of sense.

Second, Carney did not resort to the facile formula of the “rules-based international order,” which until now was an obligatory part of any Western middle power leader’s standard speech. This was an important step also since it resonates with the many countries of the non-West that have long criticized the hypocrisy and double standards of the “rules-based international order.” When a German participant in one of our programs at Global Public Policy Institute launched into an ode to the rules-based order a few years ago, she was met with horror and disbelief by the South African representatives. By describing this concept as “partially false,” Carney acknowledged the asymmetry that many in the Global South have long decried). This is an overdue step.

Lacking Honesty

The way in which Carney laid out his arguments, however, betrayed a lack of honesty. The Canadian prime minister morally ennobled his speech by invoking the Czech dissident, and post-1989 president, Václav Havel. In a 1978 essay, Havel wrote about the “power of the powerless,” describing how the communist system rested on everyone’s willingness to “live within a lie.” Just like Havel’s greengrocer, who allegedly put a communist slogan in his shop window every morning, states had reaffirmed the formula of the “rules-based international order.” It was time, Carney said, to remove these signs. This analogy is wrong in several ways.

Unlike communism, US hegemony never forced any of its allies to jointly profess belief in the rules-based international order. The US hegemonic order was an “empire by invitation” vis-à-vis European allies and Canada, as Norwegian historian Geir Lundestad put it. Especially after the end of the Cold War, the US order offered Western allies an unbeatable deal. They benefited from an unconditional security guarantee and open US markets for industrial products. They could politically oppose key US decisions, such as the Iraq War, without having to fear consequences. In 2002, former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder even won an election on that basis.

At the same time, under the protective shield of unipolar US dominance, the Europeans (and Canadians) were able to pursue a nominally “values-based foreign policy” and pretend to bless the world with “normative power Europe“ and the “Brussels effect.” It is Havel blasphemy to compare a period of extreme bliss for US partners during the “unipolar moment” with the coercive regime of communism.

Nor is forgoing the idea of the “rules-based international order” a heroic act vis-à-vis Trump. One can accuse Trump of many things, but certainly not of dressing up his raw exercise of power by appealing to international rules. In this sense, Trump stands for the end of hypocrisy. Critics from the non-West are more likely today to nostalgically remember the time when they could still criticize US power as hypocritical. In unmistakable bluntness, Trump recently argued in an interview with the New York Times that he “does not need international law” and sees himself constrained only by his own morality.

The sign of the “rules-based international order” that Carney wanted to demonstratively remove from the window in Davos had long since been burned by Trump. At first sight, one could argue that Trump’s “Board of Peace,” which is ostensibly aimed at resolving global conflicts, engages in window dressing but upon closer inspection the statutes are refreshingly honest about this neo-royalist scheme that puts Trump in charge in perpetuity while demanding $1 billion from each full member as a Mar-a-Lago Club type fee.

And What About China?

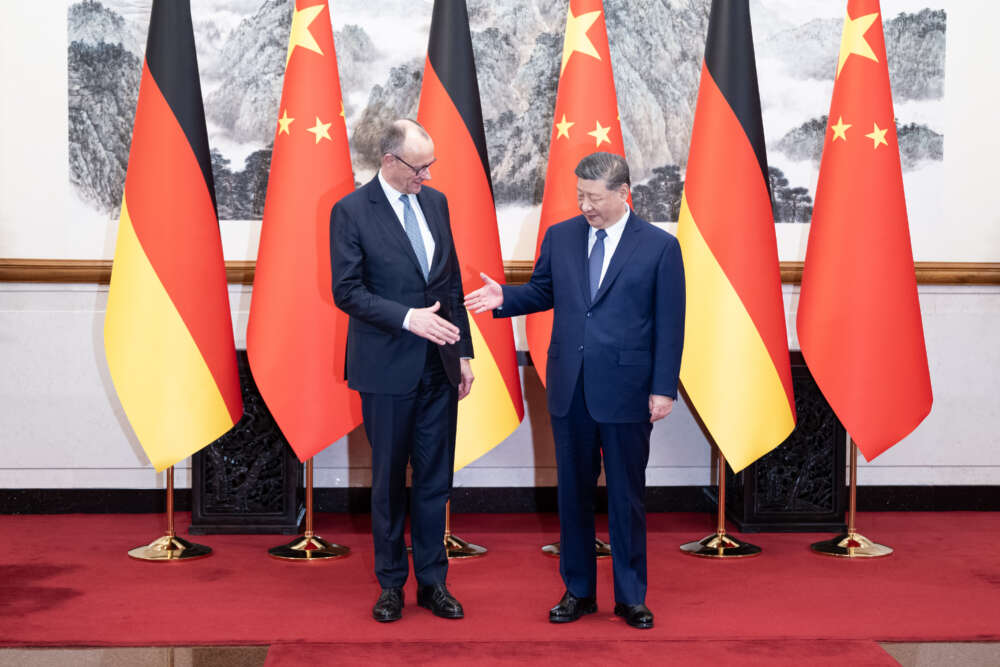

It does not add to Carney’s credibility or balance that his speech focused almost exclusively on the US power-political rampage under Trump. China’s raw exercise of power and coercion hardly features. Shortly before his appearance in Davos, Carney had paid his respects to China’s leader Xi Jinping in Beijing. In the face of President Xi, the Canadian prime minister committed to a “new strategic partnership” between Canada and China as a response to the “new world order.” Carney’s own sign reading “strategic partnership” for relations with a communist regime has far more Havel overtones than his comparison to the rules-based international order. In any case, it has nothing to do with the dictum “living in truth” that, invoking Havel, Carney claims for his own approach.

As another new sign, Carney put “values-based realism” in the shop window — a term he has borrowed from Finnish President Alexander Stubb. It sounds noble and decisive at the same time. But on closer inspection, this, too, is an overly moralized refinement of the sober, ruthless, interest-based realism that Carney is pursuing. “Optionality,” “balancing,” and “hedging” are the correct terms here, not “values-based.” Interests take precedence; values are an optional add-on. They come into play when they align strongly with interests or are not crowded out by other factors in the weighing of interests.

Given the world that Canada — and other middle powers such as Germany —face, this can be a sensible approach, provided it is pursued with the necessary realism toward the threats posed by China’s authoritarian state capitalism and hegemonic ambitions. But better not cloak it in claims of pursuing a “values-based” approach. This sets any government up for failure anyway given that implementation will be patchy at best. Rather be forthright about your realism while trying hard to live up to domestic values and apply international law consistently.

Drudgery Instead of Glamour

Carney was strongest where he was brutally honest: “The old order is not coming back. We should not mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy.” This is a very unvarnished diagnosis. But Carney did not stop there. He promised: “But from the fracture we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just.”

Certainly, one needs a dose of utopianism to avoid becoming a cynic and to mobilize energy for constructive action. But there is a fine line between motivating ambition and illusory saviorism. At the international level, from a Canadian and European perspective, it will be difficult to build a “bigger, better, and stronger” international order in the shadow of great powers on a rampage. Conditions for more international-order building are unlikely to ever be as favorable as they were during the unipolar moment after the end of the Cold War. Claiming to build a “bigger, better, stronger” order in the present moment of spiraling disorder comes across more as a theater of illusions than the audacity of hope. At any rate, before reaching for the stars, Carney and the leaders of other middle powers need to put in some hard work in order to create the basic conditions for a more productive, self-confident path.

This means, first and foremost, that a great deal of unglamorous, painstaking work is required to reduce middle power dependencies and vulnerabilities to coercion by the great powers. Only a country that cannot be easily blackmailed can confidently chart its own path. For Germany and Europe, this means working with utmost focus and determination to be able to defend Europe independently while drastically reducing dependencies on China in supply chains and critical raw materials. For many non-nuclear middle powers in dangerous neighborhoods, this also involves a consideration of whether to pursue nuclear weapons as a deterrent.

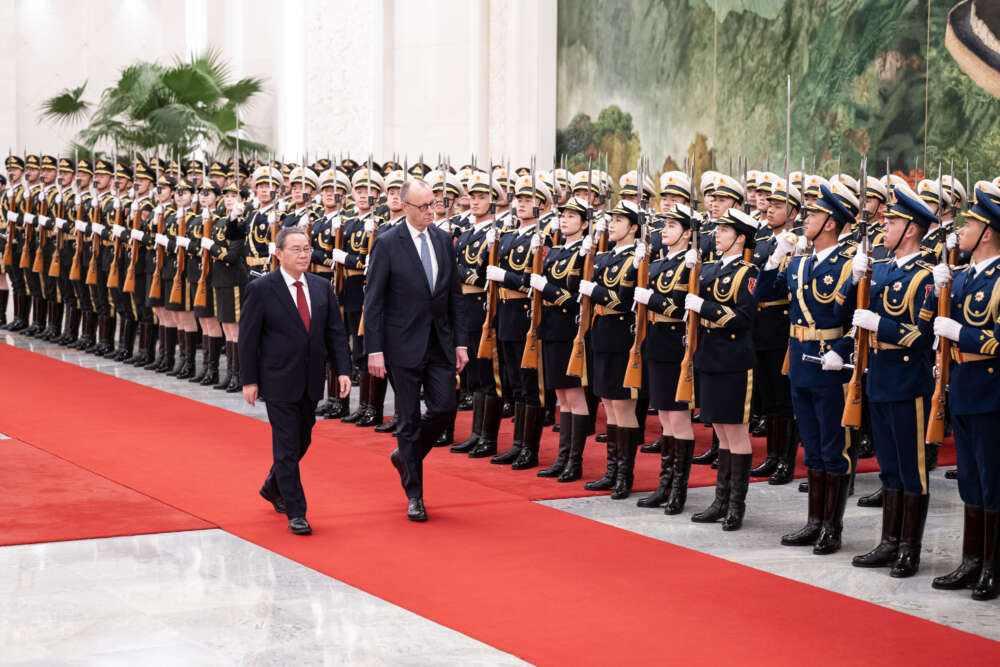

Carney’s call for middle powers to band together is based on sound analysis. He rightly pointed out that “when we only negotiate bilaterally with a hegemon, we negotiate from weakness. We accept what’s offered.” He called on middle powers to “combine to create a third path with impact” rather than competing “with each other to be the most accommodating.” But even if middle powers manage to reduce their vulnerabilities (a big “if”) this is easier said than done, especially if Beijing and Washington decide to apply divide-and-rule tactics with greater skill. After all, Carney himself was the one engaging in the competition to be the most accommodating when bowing to Xi in Beijing. This week, it’s British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s turn to pay his respects to the Chinese leader, and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz will follow later in February.

Taken to its logical conclusion, Carney’s appeal means that middle powers should come together in an anti-coercion solidarity mechanism when individual members are affected by coercive measures by great powers. Concretely, this would have meant, for example, that Europeans and Canadians would have shown clear and measurable solidarity with Japan in light of Beijing’s coercive measures following statements by Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi about Taiwan. As desirable as such a solidarity mechanism is, we are currently a long way away from it, given the heterogeneity of middle powers and their hesitation to upset great powers.

A Realistic Transformation

Carney was right to advocate flexible coalitions of willing and able states, based on joint interests. These can operate outside formal international organizations. As exciting as it is to focus on informal, issue-based coalitions, Canada and like-minded middle powers should not lose sight of existing formal organizations. Within the UN system, Canada and Europe must work together with like-minded partners on a realistic restructuring in the light of shrinking resources, global power shifts, and increasing great power competition. Many activities and organizations must be reconfigured in order to operate as effectively as possible with fewer financial resources. In the humanitarian system, for example, this requires the courage to set priorities, implement lessons learned (long overdue), and restructure in order to prevent mere bleeding out and stagnation.

All of this is worth the sweat of the noble, even if it cannot always be morally embellished. In the end, this may be precisely what generates greater credibility for Canadian and European foreign policy — also beyond the West.

N.B. This essay builds on results of a project on liberal democracies and changing global order supported by Stiftung Mercator.

This article was first published by Internationale Politik Quarterly on January 28, 2026.