Peace in Numbers: What Do Shifts in Funding Tell Us About EU Priorities?

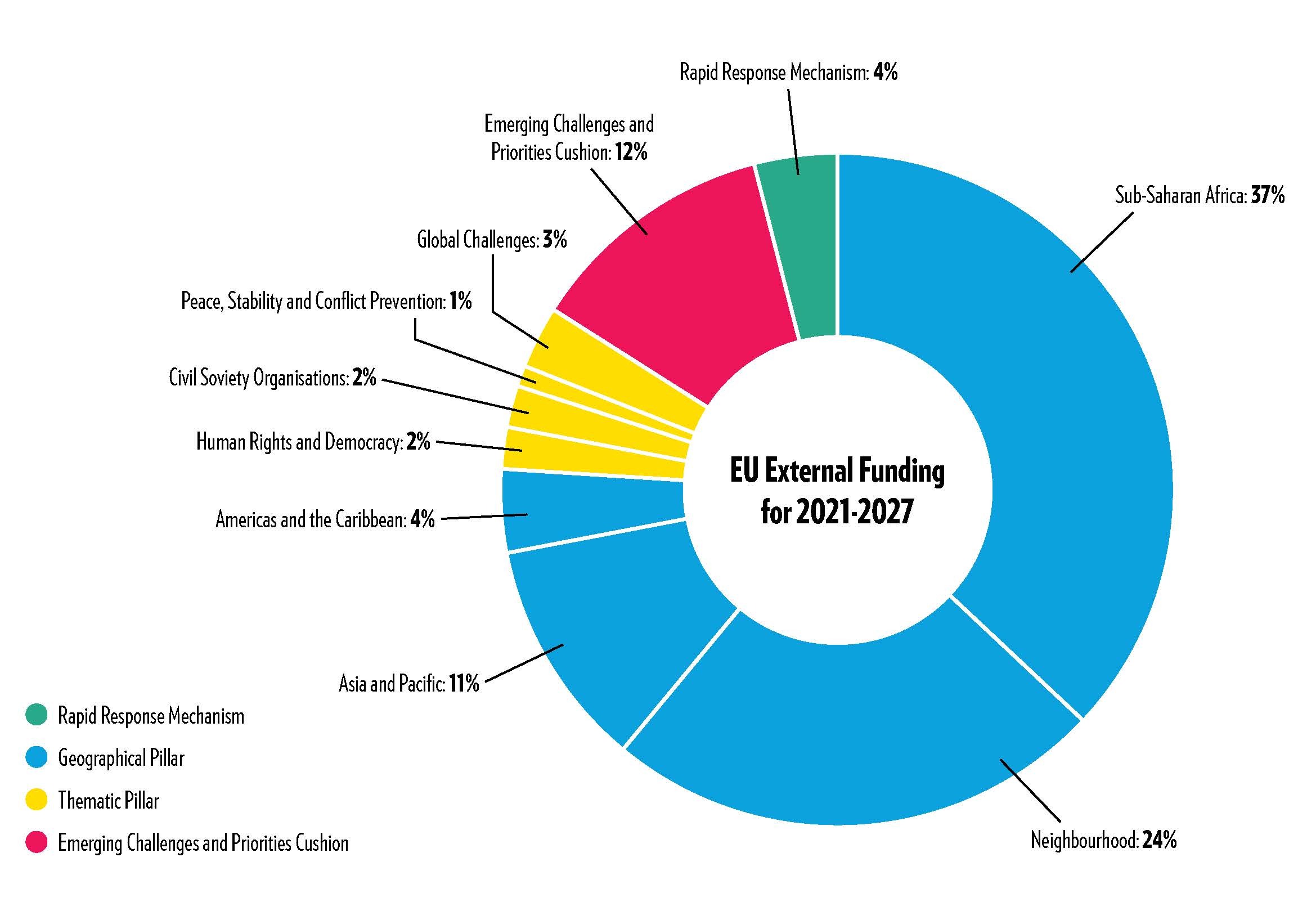

This is especially true because the Directorate-General for International Partnerships (DG INTPA) plays a central role in Global Gateway. Previously called the DG International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO), DG INTPA is the main EU actor involved in international development. Some fear that its central role in Global Gateway (and with it, its increased focus on infrastructure and private sector investment) may come at the cost of other development objectives. For example, this new focus could result in a reprioritization of spending within the 60 billion euro geographic pillar of the Neighborhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument – Global Europe (NDICI-GE), which is controlled by DG INTPA. The NDICI-GE was created for the EU’s 2021 – 2027 spending period (known as the Multiannual Financial Framework or MFF) and pools several funding instruments together into an 80 billion euro fund designed to “support countries most in need to overcome long-term developmental challenges.” The full breakdown of spending can be seen in Figure 1 below; the majority (75 percent) of NDICI-GE is spent through the geographic pillar and, for the regions Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and Latin America, this money is spent through DG INTPA.

While in some regions, refocusing on infrastructure and investment opportunities for private sector actors might be extremely helpful, in other areas, for instance, those impacted by fragility and conflict, such a focus could be unhelpful or even detrimental. Global Gateway funding is “only marginally suitable for highly fragile and conflict-affected countries.” Investments need security and good (enough) governance with calculable risks and predictability. It is thus not the right instrument for promoting security and peace, nor is it intended to be. The 225 flagship initiatives already launched or planned under Global Gateway are located mostly in emerging markets. Conversely, the few EU funding streams that are focused on addressing the drivers of conflict (such as the EU’s rapid response mechanism and those priority areas within the geographic pillar) are small and already heavily depleted. Further depleting these few funds that are still aimed at addressing the drivers of conflict could short-change needed investment in peace, security and governance to fund the geopolitical ambitions of Global Gateway.

Figure 1: EU External Funding for 2021 – 2027

Figure 1 shows a breakdown of how the 80 billion euros in the EU’s NDICI-GE is distributed. While 60 billion euros (or 75 percent) of NDICI-GE money goes into geographic programs, 3 billion euros (or 4 percent) goes to the rapid response mechanism, 10 billion euros (or 12 percent) goes to the cushion for emerging challenges and priorities, and 1 billion euros (or 1 percent) goes to the Peace, Stability and Conflict Prevention thematic area.

This worry isn’t that easy to quantify; despite the rhetoric of huge investments being made to support the Global Gateway strategy, most of the funding announced has yet to materialize. (This is complicated by the fact that mobilizing this funding will require a level of investment from member states and private companies that the EU cannot enforce.) In the absence of firm numbers, the experts and advocates in Brussels raising the alarm about the potential downgrading of peace and conflict as a funding priority in light of Global Gateway have cited more qualitative indicators, such as the Commission not including the much-anticipated strategy on fragility in its 2025 work plan. The EU’s most common retort to those concerned is that there is still a set budget for peace programming in many countries until 2027 and that, while these initiatives aren’t grabbing headlines, the EU is continuing to run them in much the same way as before.

This piece hopes to fill this gap in understanding by quantifying the EU’s shift in priorities. We used data from (1) funding allocations for the periods 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027 within NDICI-GE geographic pillar; (2) spending data on actual financial commitments, available until 2023; and (3) actual disbursements, as reported by the EU to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and available until 2023. Through this data, we can quantify the worry that funding from the geographic pillar is being shifted to Global Gateway objectives, seemingly hollowing out peace and security-related budget lines. Doing so seems to indicate that the EU is pouring investment into short-term transactional investments, which may undermine longer-term stability and peace.

Understanding the numbers

The first dataset we use is from DG INTPA’s updated multiannual indicative programmes (MIPs), which lay out EU priorities (and the allotted funding for them) for 41 countries in Africa, 16 countries in the Americas and the Caribbean and 17 countries in Asia and the Pacific. There are also three regional MIPs, but since their priorities followed a different format, these were not included in the trend tracking. These MIPs do not give an exhaustive list of all countries receiving EU funding, nor is it easy to use them to track trends (since there is no consistency in the labelling of EU priorities across countries and regions). It is possible, though, to track how much money was committed to general priorities between 2021 and 2024 and then between 2025 and 2027. The comparison is not exactly halfway through the MFF, however, by looking at the percentage (of the total funding for each period) going to each priority, we can see how priorities have shifted.

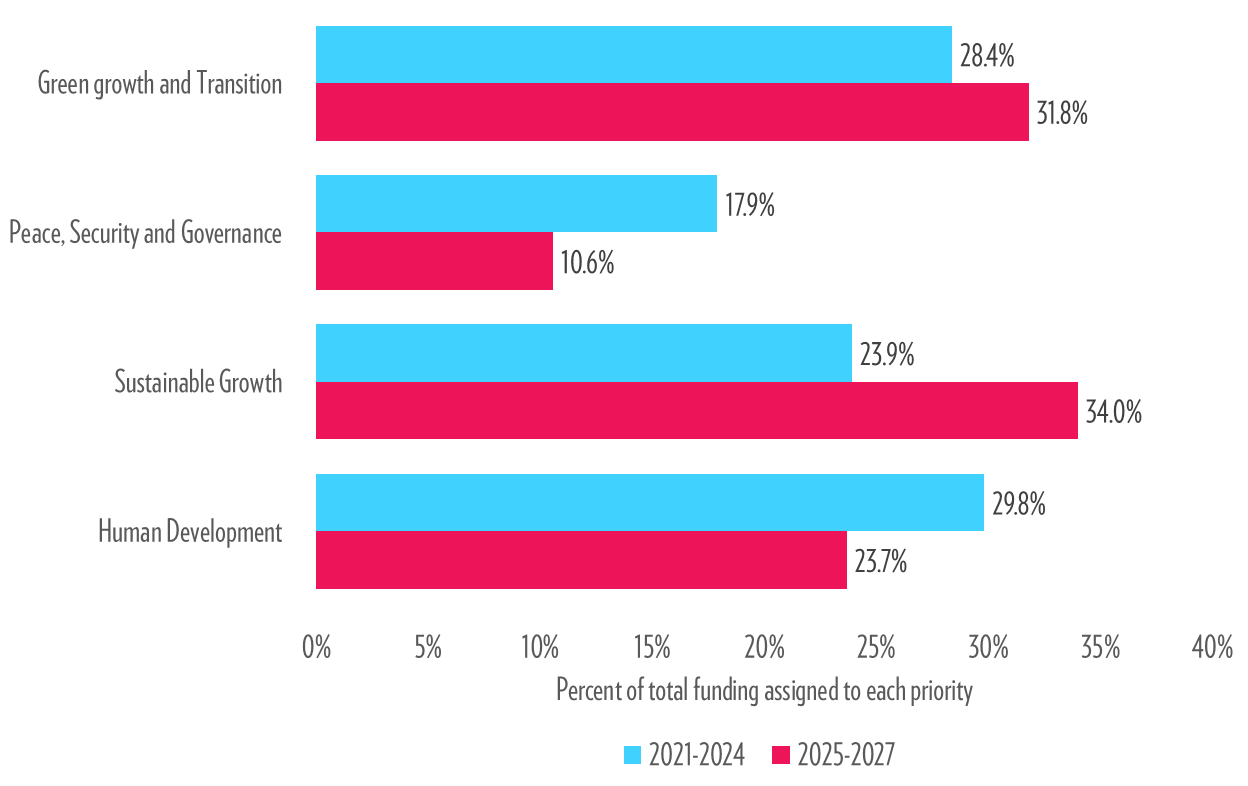

Across the 74 country programs, priorities can broadly be broken down into four main categories: “Green Growth and Transition,” “Peace, Security and Governance,” “Sustainable Growth and Jobs” and “Human Development.” These categories are not perfect, but they do go some way to illustrate the scope of priorities mentioned, while simplifying themes enough to track them in a manageable way.

The numbers from the MIPs have been supplemented by two other datasets. For 2021 – 2023, we use data on actual commitments from DG INTPA’s annual reports on the Implementation of the European Union’s External Action Instruments[1] and actual disbursements from the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS). Through the CRS, donors – including the EU institutions – report how they spent their official development assistance (ODA). The benefit of these datasets is that they cover all countries that the EU provides funding to, beyond the 74 for which MIP updates are available. Although these additional datasets are broken down into different – but again vague and broad – categories, we did our best to map the labels in these datasets to those used in the MIPs, so we could track the EU’s priorities over time across a larger number of countries. This allows us to see whether the trends emerging from our analysis of the MIPs are part of a broader trend.

Because we are using three distinct types of data (planned allocations, commitments, disbursements), we cannot claim like-for-like comparisons between absolute amounts. We can only compare trendlines. Even so, taking all this data together hopefully gives – at the very least – an insight into how EU funding has shifted and, with it, how priorities appear to have changed over the course of the MFF.

Global Gateway priorities are changing investment patterns

The data indicate that funding changes are being shaped by Global Gateway objectives. Green growth and transition received by far the most money in 2021 – 2024 and was the priority with the least funding cuts for the period 2025 – 2027 (receiving the most funding in that period too). This corresponds to the funding priorities of Global Gateway; of its five priorities, climate and energy have consistently received the lion’s share of Global Gateway funding. According to a report by Oxfam, in 2023, there were 49 Global Gateway flagship projects in the climate and energy sector, representing 56 percent of total projects that year. In 2024, climate and energy accounted for 61 projects, representing 44 percent of the total. By comparison, the second largest sector in terms of number of projects was transport, which included 17 projects in 2023 or 20 percent of total projects that year and 32 projects (23 percent) in 2024.

Funding for priorities in the MIPs related to peace, security and governance received the second most funding from the EU in 2021 – 2024; however, as of the next funding period, these priorities saw the largest-scale cuts. Now, for 2025 – 2027, funding for peace, security and governance has fallen to third place, being overtaken by sustainable growth and jobs as the second most-funded priority in this period. This shift could be interpreted as the EU trying to create enabling conditions for Global Gateway projects. The strategy has the explicit focus on using EU funds to mobilize broader investment from private companies, and one way to do this would be to invest in sustainable growth and labor market development in the countries where it engages.

An illustrative example of this was the huge investment made in the regional MIP for Africa in 2025 – 2027; here, a new budget line (“support in investments”) was one of the few that saw an increase in funding compared to the previous period. The EU explains that to ensure “a stronger alignment with the Global Gateway strategy,” the existing 1.450 billion euro envelope known as “EFSD+” was replaced with a more comprehensive and increased envelope of 4.683 billion euros meant to “serve EU and partner countries’ shared interests across different Global Gateway priorities.”

Figure 2: Changes in Funding to Different Priorities in Country MIPs Between 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027 (For All 74 Countries Counted)

Figure 2 shows the percentage of funding assigned to each of the four broad priorities we looked at within NDICI-GE’s geographic pillar between 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027. It highlights that green growth and transition and sustainable growth and jobs took an increased share of funding (as a percentage of the total spending for that funding period) in 2025 – 2027 compared to 2021 – 2024.

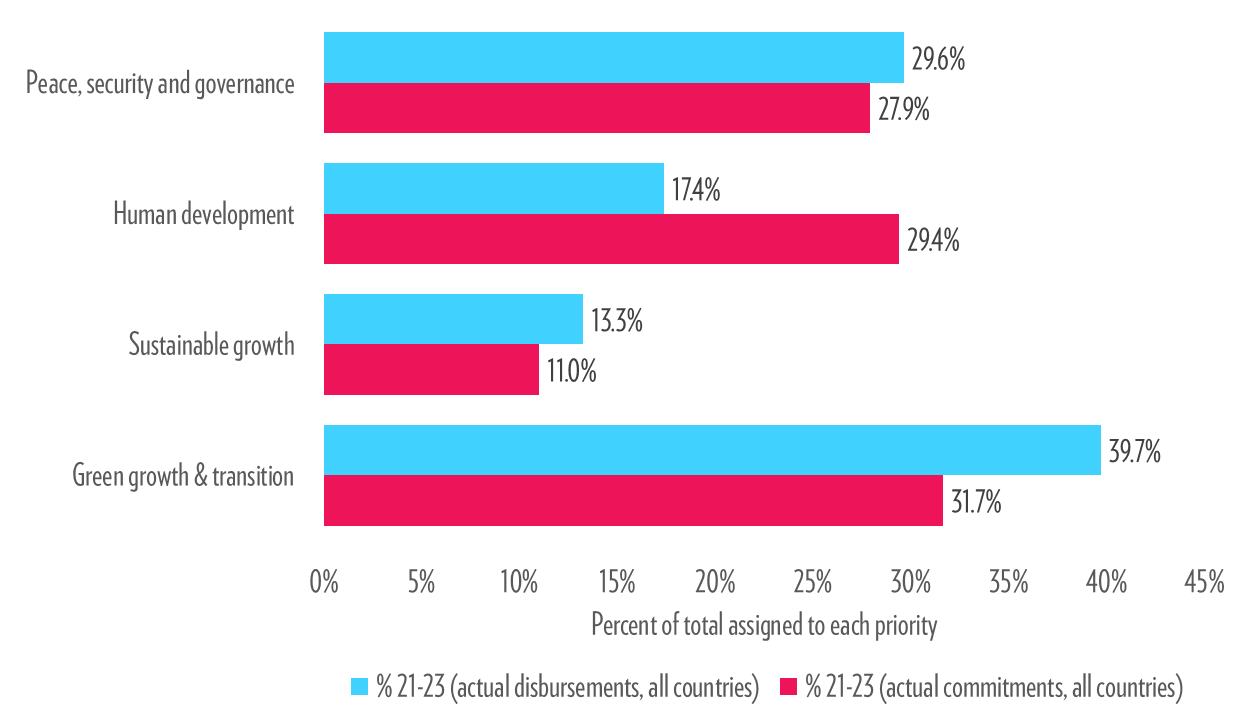

The other two datasets (commitments and disbursements for 2021 – 2023) seem to validate these findings and indicate that this shift in priorities extends beyond the 74 countries for which we were able to examine MIP priorities. By coding these two datasets, we can examine the total EU funding given to all non-EU countries and see the percentage of total funding committed/disbursed to initiatives across the four priority areas we examined. As you can see in Figure 3, this also allows us to compare how much was committed and how much was actually disbursed to these same priorities for the period 2021 – 2023. Doing so shows that, while the percentage (of total EU funding) that was committed and then actually disbursed to peace, security and governance and sustainable growth are relatively similar, there are quite significant differences for green growth and transition and human development. While the former saw a relatively significant increase in terms of the amount of funding actually disbursed between 2021 – 2023 compared to what was committed (i.e., the amount actually disbursed was much more than the amount initially committed), human development saw an even more significant decrease in the opposite direction (i.e., the amount committed was significantly more than the amount actually disbursed). This, arguably, adds further evidence that themes linked to Global Gateway received more investment, and that areas not associated with Global Gateway received less funding to balance this out.

Figure 3: Changes in Funding to Different Priorities in Country MIPs Between 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027 (Extremely Fragile Countries Only)

Figure 3 shows how the funding trends examined in Figure 1 change when we look exclusively at countries designated by the OECD as “extremely fragile.” This suggests that even in countries with obvious peace, security, governance and human development challenges, there have been cuts in funding to these areas.

What is furthermore concerning is that the reductions in allocations for peace, security and governance outlined in the MIPs do not seem to track with countries’ needs: the same funding trends are evident in countries designated by the OECD as “extremely fragile.” These are countries facing economic, environmental, human, political, security and/or societal risks, that lack the systems and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate them. Given this fragility, one might assume that these are the very countries in need of investments in peace, security and governance and human development. However, isolating just these countries in our data shows that funding for both peace, security and governance and human development was severely cut between 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027 (as a share of total funding) and that both green growth and transition and sustainable growth saw an increase in investment between 2021 – 2021 and 2025 – 2027 and were the most funded priorities in the latter period.

Figure 4: Changes in Funding to Different Priorities in Country MIPs Between 2021 – 2024 and 2025 – 2027 (Extremely Fragile Countries Only)

Figure 4 shows how the funding trends examined in Figure 1 change when we look exclusively at countries designated by the OECD as “extremely fragile.” This suggests that even in countries with obvious peace, security, governance and human development challenges, there have been cuts in funding to these areas.

Empty talk on peace and security?

Many EU officials we have spoken to during this research have reassured us that the worry over NDICI-GE deprioritizing peace, security and governance is overblown. They often argue that priorities set in MIPs back in 2020 have remained the same, and that work in peace, security and governance is carrying on just the same – but is just not getting the same airtime as big initiatives like Global Gateway.

To their credit, peace, security and governance-related priorities were not forgotten in MIPs; they are mentioned in 66 of the 74 country MIPs we looked at. However, the problem is that in almost every single case, they received less funding than any other priority.[2] In some instances, like the MIP for Togo, despite being mentioned, funding for peace, security and governance was slashed from 29 million euros in 2021 – 2024 to zero in 2025 – 2027. There were also some exceptions, like Cabo Verde (where the total funding is relatively low anyway) or the Kyrgyz Republic (where peace, security and governance receive more funding but are lumped together with digital transformation). Overall, this suggests that, in terms of funding, peace, security and governance are not seen as the most pressing priorities.

Of course, it could be argued that monetary investment is not the best way to measure prioritization because some things simply cost more than others. If green growth and transition require building massive renewable energy projects and transmission infrastructure, and peace, security and governance mean organizing dialogue projects or training workshops, then the former will cost more. However, the funding mechanisms available for addressing the drivers of conflict and instability were already small and heavily depleted. So, the fact that the limited funding which did exist within the NDICI-GE geographic pillar, to address governance, peace, security and development challenges, was heavily cut between the two halves of the MFF raises serious questions about how the EU can address these challenges.

Is the EU short-changing its security?

Investments in Global Gateway are important, but our analysis suggests that these investments are coming at the expense of peace and security-related funding. We already know that many of the funding mechanisms aimed at addressing the drivers of conflict (such as the rapid response mechanism and the emerging challenges and priorities cushion) are severely depleted, so the fact that this seems true for NDICI-GE funding (and potentially all EU funding given to non-EU countries) raises serious questions about the EU’s approach in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

If the EU allows these countries to fall through the cracks, it risks inadvertently allowing instability and fragility around the world to thrive, with implications for the security of the EU. In other words, short-changing investment in more holistic funding for peace and security by focusing on Global Gateway priorities is a mistake. We know that violent conflict in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa or the Sahel can disrupt trade routes, stunt the national and regional growth of potential EU partners, lead millions of people to flee their homes, and exacerbate the spread of drugs and weapons. If the EU slashes funding related to peace, who will support the initiatives needed to stop enduring threats, like the proliferation of armed groups, organized criminal networks, and violent and proscribed groups from impacting European safety and security?

These activities don’t cost a lot: collective spending for saving lives in humanitarian emergencies – helping poorer countries adapt to the climate crisis or reestablish stability and peace after armed conflicts – peaked in 2023 at less than 100 billion euros and has since turned sharply downward. We are not calling on the EU to dramatically increase funding for peace and security or even to aim to invest the same amount in activities related to more holistic understandings of peace as they do in geopolitical power projection. However, further depleting the already small pots of funding that do exist for peace not only further endangers those in conflict-affected and fragile contexts but also inevitably undermines European security and interests. Now that we have even further evidence that this is happening, we need to look at how to reverse the trend.

[1] For 2021 and 2022, we used the consolidated tables provided by the independent study evaluating the EU’s external financing instruments (which served as the basis for the EU’s mid-term review of these instruments). For 2023, we added new data from the original Commission report.

[2] A similar pattern can be seen with human development, which was mentioned in an countries 21 out of 41 MIPs for African countries, but like peace, security and governance is generally allocated less and less funding. For instance, in Nigeria human development was allocated 154 million euros in 2021 – 2024, but received no funding for 2025 – 2027.