Time to Strengthen the EU’s Engagement in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States

By JULIAN BERGMANN (IDOS), ABI WATSON (GPPi)

The world is experiencing conflict and insecurity at levels not seen since the Second World War. Several parts of the world are teetering on the edge of large-scale violence. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 61 countries are experiencing high or extreme fragility. These countries are facing economic, environmental, human, political, security and/or societal risks and lacking the systems and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate them. Given that the European Union is active in almost all 61 of the countries on the OECD’s list and many of the countries impacted by violent conflict, it is both surprising and concerning that fragile and conflict-affected states do not play a more central role in the EU’s international strategy.

Recently, EU foreign policy discussions have been dominated by its Global Gateway and Re-Arm strategies, both of which are receiving significant monetary and political support. Since 2021, the Global Gateway strategy has seen a dizzying number of infrastructure investments around the world. The more recently announced Re-Arm Europe plan, meanwhile, is rallying the EU and its member states to mobilise a staggering 800 billion euros for military defence. While these initiatives are welcome steps forward in addressing gaps in European defence and geopolitical policies, there is a risk that other important issues — like EU engagement in fragile and conflict-affected countries and addressing the drivers of fragility and conflict — are deprioritised to facilitate the surge of political and financial investment in these flagship initiatives.

Has the EU Lost Its Way on Fragility and Conflict?

The European Commission has acknowledged the need to improve the EU’s approach to fragile and conflict-affected contexts. Late last year, it mandated the Commissioner for Crisis Management, Preparedness and Equality, Hadja Lahbib, to lead the development of a Commission-wide integrated approach to fragility. With this move, the new Commission signalled its ambition to push for a more coherent and joined-up approach to engaging in conflict-affected and fragile countries. There were also promising signs that the EU’s approach to fragility and conflict might be sufficiently funded. For instance, Commissioner for International Partnerships Jozef Síkela, noted in his evidence to the European Parliament at the end of 2024 that “beyond Global Gateway, the EU should maintain dedicated resources to engage in fragile and conflict settings.” However, now in 2025, developments on these issues are less encouraging.

Although it was anticipated, an official communication on the EU’s fragility approach was not included in this year’s Work Programme for the Commission. Rather, the Programme only mentions the ambition to review how to best tackle fragility within current budgetary availabilities and through existing instruments, dampening any hopes that the EU might try to take a more strategic approach to fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

Worse than that, there is even less EU funding for conflict and fragility than before. Take the two funding streams developed to allow the EU to respond more flexibly to conflict and crisis: the rapid response mechanism (3.2 billion euros) and the cushion for emerging challenges and priorities (9.53 billion euros). An independent review of external financing instruments of the EU said: “The succession of severe global or regional crises” seen since 2020 “has been weathered but depleted the EU’s flexible funding sources.” In other words, halfway through the EU’s current funding cycle (2021−2027), flexible funding has already been heavily depleted, predominantly by spending in the EU’s enlargement and neighbourhood areas like Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Ukraine. This leaves the EU with little unallocated funding for peace and security challenges until 2027, raising serious questions about how it will deal with crises, like in Sudan, or political opportunities for peace — or the consequences of the opposite — like in Syria.

This is especially true given how much peace and conflict seem to be sidelined by other funding instruments within the EU. For example, the geographic pillar of the EU’s Global Europe: Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) includes 60 billion euros allocated by country and regional Multiannual Indicative Programmes (MIPs), which outline how much money will be given to the two to three country or regional priorities. An independent study found that even when peace was a priority in these country programs, key staff often expected that other instruments (like the rapid response pillar) would “deal with peace and security,” despite their much smaller budgets.

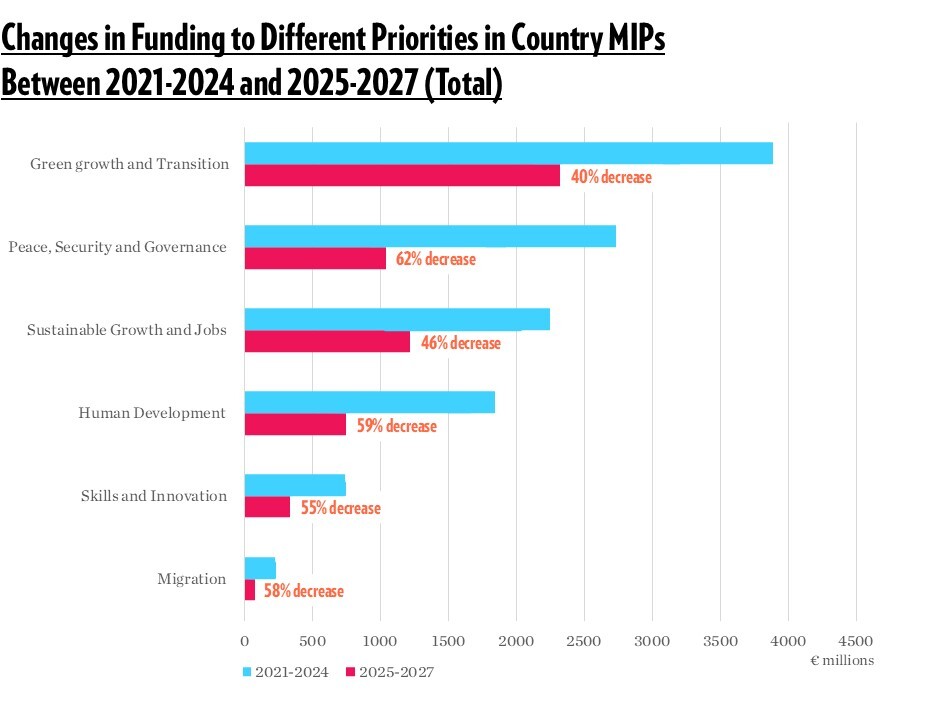

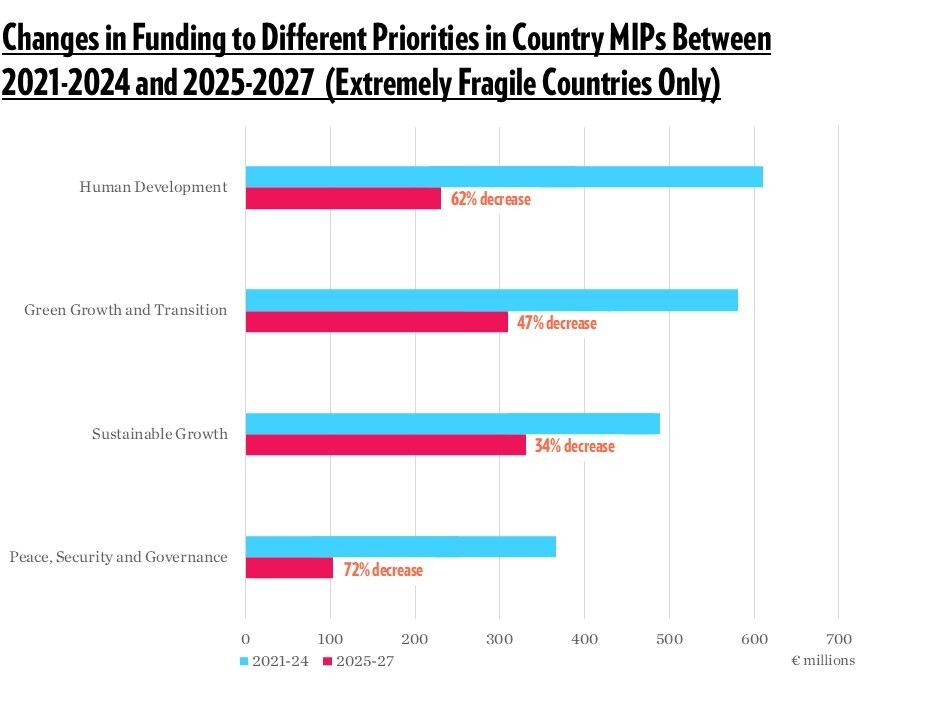

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, to see that funding for “peace, security and governance” has been cut between the first and second half of the EU’s seven-year funding cycle. By grouping similar priorities in the MIPs of 74 countries in Africa, the Americas, the Caribbean, Asia and the Pacific, it is possible to track how much money was committed to what themes between 2021 and 2024 and between 2025 and 2027. Doing so shows peace, security and governance was cut on average by 60%. In extremely fragile countries, cuts in this area are even larger, averaging 72% between the two periods.

Cutting these budget lines is a mistake. Addressing the drivers of fragility and conflict in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, the Sahel and elsewhere is not only the right thing to do, but it is in the interests of the EU. Violent conflict can disrupt trade routes, stunt national and regional economic development, serve violent proscribed groups, displace people around the world, and shrink the community of nations that respect human rights and democratic values. The fact that around 50 percent of Global Gateway partner countries experience high or extreme levels of fragility, for instance, is not insignificant. Geopolitical rivals like Russia and China are also exploiting the fragility of conflict to expand their military and economic influence.

What is Needed for a Strategic, Well-Funded Approach to Fragility and Conflict?

It is too late to place the integrated approach to fragility on the Commission’s Work Programme for this year, but it is absolutely not too late to put fragility and conflict squarely back on the EU’s list of priorities. Doing so would strengthen the bloc’s focus on prevention and ensure that the EU’s engagements in fragile and conflict-affected contexts have a long-term orientation. It would also provide new impetus to the EU’s long-standing mission to better align different instruments across policy domains. There is definite room for improvement in this area, for example, when it comes to the EU’s implementation of a humanitarian-development-peace (HDP) nexus approach in fragile settings.

It is time for a new EU strategic framework for fragility and conflict. This new framework should be developed in collaboration with relevant EU institutions and — perhaps more importantly — member states. The involvement of member states is crucial because they are largely responsible for shaping the EU’s engagement in fragile and conflict-affected settings. The development of a new strategy could also benefit from the expertise of certain member states that have been at the forefront of developing better approaches to fragility and conflict. Countries like Germany should use their power and experience to shape upcoming processes.

The EU’s new approach should not duplicate existing frameworks but should strengthen current instruments and tactics for addressing fragility. For instance, fragility indicators could be added to the conflict analysis exercises that the EU is already doing as part of the multi-annual programming of NDICI. Moreover, there is a need to strengthen the Team Europe approach in fragile and conflict-affected contexts, for instance, by enhancing information sharing and joint analysis among European actors. Since EU delegations are best placed to facilitate stronger Team Europe cooperation, the recently announced plans to reduce EU delegations may be ultimately self-defeating in this regard. Similarly, delegations can play a role in improving monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to strengthen knowledge exchange and learning on the EU’s engagement in fragile and conflict-affected states. These kinds of learning and review mechanisms are crucial to the success of any new strategy.

Of course, another EU strategy alone will not be sufficient to strengthen the EU’s engagement in fragile and conflict-affected states. Without funding, a strategy will amount to little more than a piece of paper. As negotiations for the next EU funding cycle approach, there needs to be a clear policy discussion about how engaging in fragile and conflict-affected states is in the interest of Europeans. Germany and other member states could be crucial advocates for a more effective EU approach to fragility and conflict.

Disclaimer

This article was written after a joint GPPi-IDOS workshop, which discussed the place of peace and conflict and the contributions Germany could make. It does not represent the views of the participants that attended, but solely those of the authors. The work draws on GPPi’s work on EU funding and IDOS’ research and policy advisory work on EU development policy.