Britain Knows It’s Selling Out Its National Security to Huawei

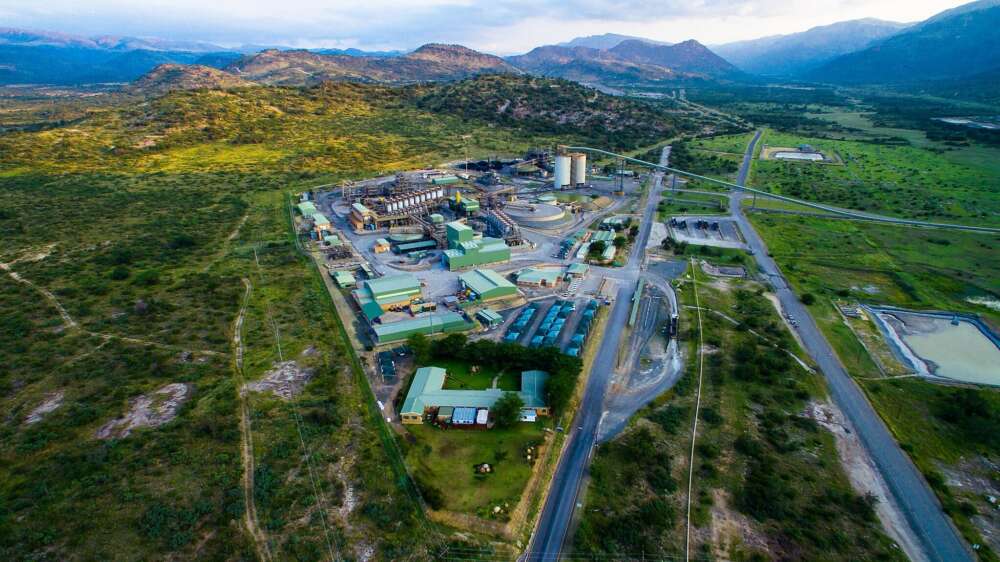

On Tuesday, much to the chagrin of the United States, the British government announced its decision to allow the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei involvement in the rollout of the country’s next-generation 5G mobile network that will run everything from self-driving cars and remote health services to industrial production. There are mounting concerns that dependence on Chinese technology for 5G critical infrastructure will make countries vulnerable to espionage, sabotage, and blackmail. This is why Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and the United States took the lead in banning Huawei from 5G rollout.

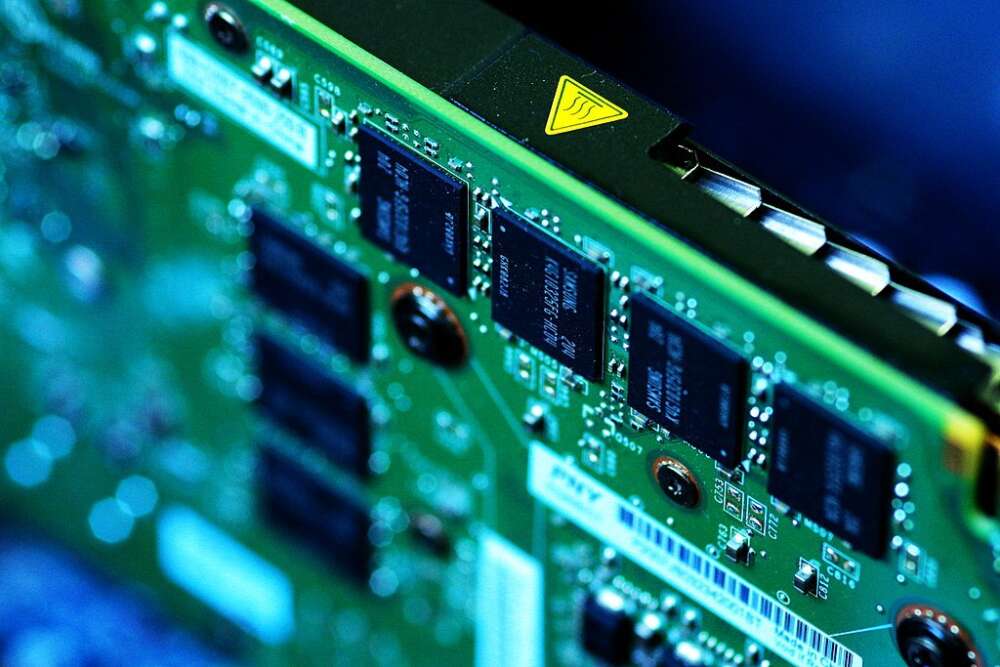

The United Kingdom has now broken ranks with many of its closest allies, including fellow members of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing club. The British government classified Chinese company as a “high-risk vendor” and banned it from the core network that manages access and authentication, but nevertheless permitted it to compete for up to 35 percent market share in the country’s access network — that is, its antennae and similar equipment.

The U.K.’s decision comes at a critical moment for Europe, with many countries in a heated political debate over how to handle Huawei. The company celebrated Britain’s decision, with Vice President Victor Zhang saying the company feels “reassured” by Britain’s “evidence-based” decision. The company hopes that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s policy will influence the rest of Europe and beyond. After all, the U.K. is considered a heavyweight on security policy — if the U.K. doesn’t see a need to exclude Huawei, why should anyone else?

But the U.K. shouldn’t be a model for countries in Europe — or anywhere else, for that matter. Upon closer inspection, the British government’s reasoning, and the basic assumptions underlying it, are eerily lightweight and sometimes openly self-contradictory. A far more persuasive model for dealing with Huawei arrived this week in the form of the European Union’s newly published “toolbox” on 5G security.

The real reason for Britain’s nonexclusion of Huawei was kept under wraps by its government: fear of retaliation. After Brexit, London sees itself as dependent on Beijing’s goodwill. In an interview with the Global Times on Jan. 20, the Chinese ambassador to Britain made it clear that an exclusion of Huawei would severely damage economic and political relations. And for Johnson, the threats from Beijing — a government with expansive control over its national economy — were more credible than those of U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration.

Of course, fear isn’t much of an appealing public justification, especially for someone such as Johnson, who wants to project the image of a fearless leader. That’s why the government has come up with an extensive technical justification for the decision — an explanation that’s full of contradictions.

In fairness, Britain emphasizes that it is a “UK solution for a UK context,” which “isn’t easily replicated” by others. The reason for this is simple: Very few other countries possess the highly specialized resources — including test centers with independent software engineering capabilities and in-depth supply chain reviews — that Britain uses to deal with Huawei. “We’ve always treated them as a ‘high risk vendor’.” and “we’ve never ‘trusted’ Huawei,” wrote Ian Levy, technical director at the National Cyber Security Centre. “The move to 5G is another evolution of the technology and our security mitigations need to evolve again.”

This reasoning prompted Bob Seely, a Conservative member of Parliament, to ask why the country needed high-risk providers in its network at all. The British government has no convincing answers. It argues that due to a “market failure” there are not enough high quality providers and therefore Huawei cannot be left out. Yet Europe is home to two of the world’s leading vendors, Ericsson and Nokia; Samsung offers yet another alternative from a trustworthy democracy.

If the British government was truly concerned about market failures, it would not reward Huawei, which profits from unfair support by Chinese state capitalism, giving it advantages over its competitors from market economies. The UK, for example, could force providers to work with open coding standards (“OpenRAN”) that would ensure interoperability between providers, thus lowering market entry barriers to future market entrants and disadvantaging Huawei, which has heavily bet on closed proprietary solutions. That the British government’s test center has consistently found Huawei’s coding to be dangerously sloppy makes the green light to Huawei even more incomprehensible.

Moreover, Britain’s approach to 5G security relies on a distinction between core and access networks that the government itself acknowledges is essentially meaningless in a 5G world where computing power (and vulnerabilities through software updates) moves ever more toward the edges of the network. That is why the British government, like the EU commission, identifies sensitive functions in all parts of the network, making it close to impossible to fully isolate risks from any single supplier. How, then, will Britain decide which 35 percent of its population should depend on a network run by technology from a high-risk provider like Huawei? The citizens affected will have a simple question for their members of Parliament: Why is my security worth less?

The EU’s approach shows how one can avoid such problems. Its 5G policy states that nontechnical risks such as political dependence or sabotage by a third country cannot not be countered by technical measures. The complete exclusion of high-risk providers from all parts of critical 5G infrastructure is therefore the only sensible course of action.

Indeed, that’s the course of action the UK government decided on in 2018 with regard to the Chinese provider ZTE. It excluded ZTE from the complete U.K. communications infrastructure because of “national security risks” that “cannot be mitigated.” It’s only logical to do the same with regard to Huawei, given that the risks are similar. As Handelsblatt reported this week on the basis of a confidential memo from the German Federal Foreign Office, the United States presented clear “intelligence information” at the end of 2019 proving very clearly “that Huawei cooperates with China’s security authorities.”

Johnson’s decision to make high-risk provider Huawei part of its 5G networks is that of a nation that has given up on technological sovereignty. Driven by pro-Beijing business interests and post-Brexit fears, the UK is making its most critical infrastructure dependent on technology controlled by China’s Communist Party, thus opening itself up to further blackmail and sabotage.

Europe, for its part, does not need to be afraid of excluding Huawei. As EU Commissioner Thierry Breton points out, Europe doesn’t need to fear rollout delays because two European suppliers are at the ready. A united EU, moreover, is a formidable economic power ready to face any threats of Chinese retaliation. It would send a fatal signal of weakness to Beijing if EU countries were to take incalculable security risks out of fear. EU members should follow the example of Australia, where Huawei was excluded in 2018. “No one in the Australian political system regrets those decisions today,” Australian parliamentarians said in a message to their European counterparts. Today, Australia is a global leader in 5G deployment. This shows that Europe doesn’t need to choose between security and technology. It’s unfortunate that Britain now feels that it must.

This commentary was originally published in Foreign Policy Magazine on January 31, 2020.