Hong Kong: What’s Next and How Should Europe Respond?

Hong Kong is in a deep crisis that is spiraling increasingly out of control. The current protests were sparked in June, when two million Hong Kong citizens (a quarter of the population) peacefully demonstrated against a bill that would have legalized the extradition of suspects into the People’s Republic of China’s notorious criminal justice system. Even though the Hong Kong government withdrew the bill at the end of October, there appears to be no end in sight for the demonstrations. The current protests build on the failed 2014 Umbrella Movement, which aimed to achieve a gradual democratization of Hong Kong. On this front, concessions remain highly unlikely, even though democratization was promised in China’s 1984 treaty with the United Kingdom and the Hong Kong Basic Law was enacted on this basis.

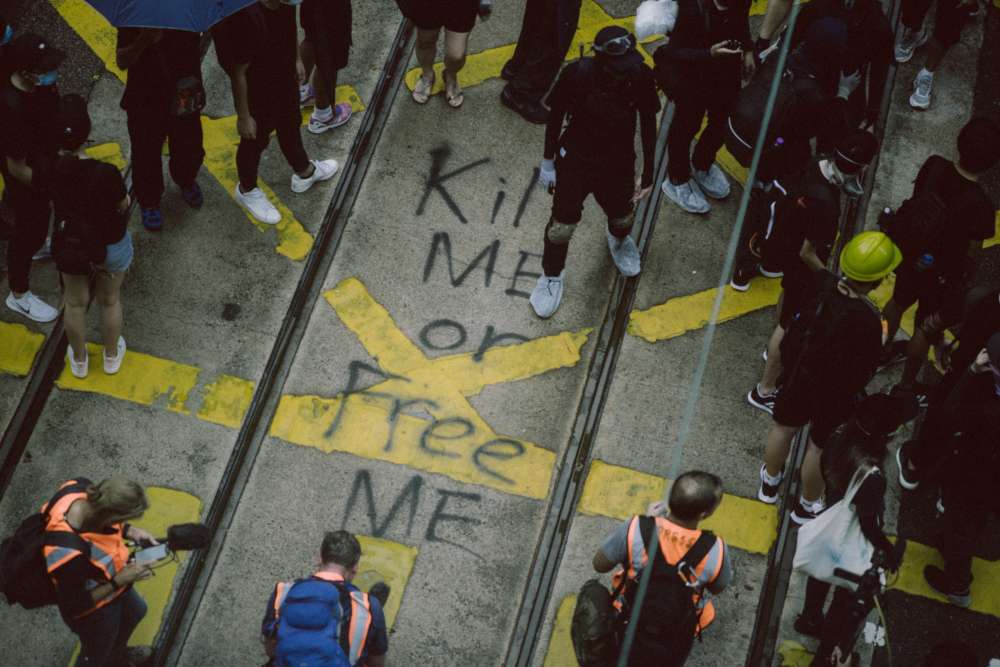

In the months since the demonstrations began, Hong Kong police have repeatedly used excessive force, while young protestors – operating without visible organization – have developed an increasingly flexible and unpredictable protest repertoire. Last week saw an escalation in violence as university buildings were defended with Molotov cocktails, burning arrows, and catapults, and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University came under a full-blown siege. Attempts at de-escalation are being hindered by the lack of leadership within the protest movement as well as by the absence of democratic structures and the limited real decision-making power of the Hong Kong government. If the district council elections that are scheduled for November 24 take place, they could serve to strengthen the pro-democracy political wing – but even this would hardly change the actual balance of power.

While Hong Kong’s legal system is essentially liberal, it remains controlled by the authoritarian Chinese party-state. The Hong Kong judiciary continues to make important decisions, including most recently the High Court decision on the unconstitutionality of a ban on face masks. But whether the Hong Kong courts can limit the erosion of fundamental rights that is the result of pressure by the central Chinese authorities remains very much in doubt, especially if their hostile reaction to the High Court’s recent decision gives any indication. In a move that is as alarming as it is startling, the Legislative Affairs Commission of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee opined that “whether laws created by the Special Administrative Region conform to standards set in the Hong Kong Basic Law can be judged and decided only by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee. No other organ has the authority to make a judgment and decision.” In other words, the central authorities are now trying to strip Hong Kong’s to-date autonomous judiciary, including its highest court (the Court of Final Appeal, yet to decide about the face mask ban in final instance), of the power to interpret the Hong Kong Basic Law. This is in direct contradiction with both Article 158 of the Basic Law and case law on this provision, which has arguably reduced but not annihilated the High Court’s powers of interpretation.

Xi Jinping is determined not to lose political control over Hong Kong. Such a development would directly threaten his hold on power, and he will do anything to prevent that from happening. On November 14, he indicated in a speech that the continuation of the ‘one country, two systems’ principle currently applicable to Hong Kong was not guaranteed. As a next step, Beijing could use the People’s Armed Police, a paramilitary force, or even the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) – which was already involved in clean-up operations over the weekend – to crush the Hong Kong protests. Again, the Basic Law would allow the Beijing-controlled Hong Kong government to ‘request’ the PLA’s assistance. Critical observers fear that the central government in Beijing is deliberately letting Hong Kong ‘burn’ in order to use the growing crisis to justify a violent crackdown. Even so, the Chinese central authorities would likely try to avoid the reputation damage caused by a massacre, preferring more covert forms of political repression.

A further possibility would be the imposition of a state of emergency in accordance with the Basic Law. This would risk the disintegration of the city’s prized rule of law through the temporary application of ‘relevant’ mainland laws – with potentially disastrous consequences for Hong Kong’s civil society. Even without the formal declaration of a state of emergency, Hong Kong is being pushed by the Chinese central authorities to introduce new legislation to defend ‘state security’ in accordance with Article 23 of the Basic Law. This, too, could undermine human rights. Both the use of existing, colonial-era emergency legislation and the employment of emergency powers under the Basic Law or legislation yet to be enacted would engage Hong Kong’s obligations under legislation incorporating the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which sets important limits to human rights restrictions in emergencies. These limits, as well as the ICCPR’s stringent requirements for the proclamation of a state of emergency, must not be violated.

The protestors’ repeated calls for support from democratic foreign countries have yet to be answered. European warnings against violence have so far avoided a clear stance in favor of the peaceful protesters and their demand for democracy. The UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has initiated consultations with his German and French counterparts to discuss possible European reactions to the crisis in Hong Kong. They should issue clear warnings that Hong Kong’s special status under international law must be respected and identify specific consequences in the event that Beijing attempts to (further) undermine the city’s status.

In the US, the imminent passing of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act threatens consequences for Hong Kong’s trade status. It is difficult to predict who would suffer more from any sanctions imposed as a result – the people of Hong Kong or the central government in Beijing. Nevertheless, it is right to think about possible levers and sanctions that could discourage Beijing from fully incorporating Hong Kong into its own illiberal system. This won’t be easy, and any attempt can only succeed if democratic states stand together. Given that not all 28 EU member states see eye to eye on China, it would undoubtedly come as welcome news if the UK, France and Germany agreed on a joint response to the crisis in Hong Kong.

If a state of emergency is declared in Hong Kong, European governments should stress the relevant requirements of the UN Human Rights Covenants applicable to Hong Kong and meticulously check — in the context of the United Nations — compliance with these stipulations. They should also review EU export controls applicable to Hong Kong and adjust these regulations to the new situation. Furthermore, Berlin should reconsider the ongoing preparations for the special EU-China Summit being planned for 2020 in the German city of Leipzig. It would be unacceptable for Germany to court a highly repressive party-state by holding an extraordinary summit of this kind, and it is also unclear what strategic objectives Berlin hopes to accomplish by courting China under such circumstances.

We should stop thinking of our relationship with authoritarian powers solely in terms of a choice between containment and engagement. Instead, we must focus on managing and reducing Europe’s own vulnerabilities as a result of authoritarian influencing. European governments must pay more attention to China’s authoritarian reach beyond its borders. Beijing’s international influence raises serious concerns for Europe, ranging from protecting critical infrastructure like the 5G network to defending freedom of speech in domestic European institutions.

Hong Kong students at German universities have already reported isolated incidents of harassment by fellow students from the Chinese mainland, including the destruction of posters and even threats of physical violence. Such intimidation is intolerable. We must watch out for and take action against intimidation on European university campuses. A blanket equation of all mainland Chinese students with the Beijing regime would, however, be equally wrong. Europe’s influence on the Chinese party-state’s decisions may be limited, but our universities offer a vehicle to help foster urgently needed understanding between young people from Hong Kong and mainland China. In light of the dramatic situation at Hong Kong’s universities – and the leading role that students and lecturers have played in the democracy movement – European universities should also prepare for a possible exodus of academics and students who would need support to reintegrate into academic life outside of Hong Kong. In addition, European think tanks and research institutions could make a greater effort to investigate the increasingly totalitarian Chinese party-state, expose its violations of the law, and improve our understanding of the multifaceted movements of protest and resistance against the PRC’s dictatorship.

A German version of this commentary was originally published by Welt Online on November 19, 2019.