Technological Sovereignty: Blind Rage Against the US is Not Enough

“The concept of technological sovereignty is poised to emerge as one of the most important and contentious doctrines of 2015”, predicts Evgeny Morozov in a recent op-ed. Indeed, the digital hegemony of the US in the form of the NSA, the military and the Silicon Valley behemoths has triggered reactions from a diverse set of players. Mindful of their digital inferiority, countries from Germany and Brazil to China and Russia have all announced measures to “regain technological sovereignty”. The US stands on shaky political ground when ringing the alarm bells on the harmful effects of the internet as a truly global medium. As Morozov correctly points out, many countries are not afraid of a “balkanization” of the internet as a consequence of pursuing a more independent path. They merely see it as a much-needed “de-Americanization” of the web.

Precisely because the US has lost its credibility as a defender of an “open and free” internet, it is of critical importance how Europe positions itself in the debate on “technological sovereignty”. It is for good reason that none of the policymakers using the term have thus far offered a precise definition. This allows them to sell a grab bag of measures under this label. It is all the more important to unpack the uses of the term and to dissect the stated goals, the underlying motives as well as the effectiveness of the measures proposed and their potential side effects. GPPi and New America’s Open Technology Institute have tried to do exactly that in a recent study that looks at technological sovereignty proposals that have emerged in the European Union following the Snowden leaks in 2013.

Comparing various proposals across the globe, different goals and motives do matter. There are at least five different motives for introducing measures for greater “technological sovereignty”. Three of these goals include the protection of government secrets, industry secrets and the data of citizens against espionage and foreign surveillance. The fourth goal is to support domestic digital industries in a competitive global marketplace. The fifth is greater government control over the digital lives of its own citizens. It is easy to see why the fifth goal is very different from the other four. Here, the authoritarian state is “sovereign” vis-à-vis its own citizens. There, citizens and their democratically elected representatives are “sovereign” over their own data. Morozov discusses China’s and Russia’s crackdown on internet freedoms in the name of “technological sovereignty” in the same breath as Brazil’s plan to build new undersea cables that bypass the US. Even worse, he also ends up justifying the actions of authoritarian states such as China and Russia. He says that these countries “are simply responding to the extremely aggressive tactics adopted by none other than the US”, and that “their actions are proportional to the aggressive efforts of Washington to exploit the fact that so much of the world’s communications infrastructure is run by Silicon Valley”.

So cracking down on your own citizens is a “proportional” response to whatever misgivings a country has about the uneven distribution of digital power in the world? It takes a much distorted sense of proportionality to arrive at this conclusion – one that sees “concerns over domestic unrest” as a legitimate reason to “exert more control over digital properties”. Why this moral equivalence between democratic and authoritarian regimes?

Certainly, independent analysts and public intellectuals have a duty to speak out if they are serious about the values of liberal democracy and open society. It is perfectly possible to rally against the hypocritical behavior of democracies such as the US, the false promises of Silicon Valley and the abusive behavior of autocratic regimes. Unless, of course, you are so blinded by your rage against the power of Silicon Valley that you see anyone willing to stand up to US power as an ally. There is a historical precedent for this: Western leftist intellectuals so disenchanted with their own capitalist societies and so desperate for an alternative that they ended up legitimizing real communism despite all its abuses. In the debate on “technological sovereignty” we should not fall into the same trap. “De-Americanization” of the web only makes sense if it does not make the internet less free. Therefore, we should conduct the discussion on “technological sovereignty” mindful of our fundamental values and with a view to the effectiveness of measures. This means, first of all, pursuing alliances with democratic states that share European values of internet freedom. Here, the natural partner is Brazil which recently concluded a very progressive regulatory framework with the “Marco Civil da Internet”. Together with Brazil, Europe should also convince large democracies in Asia such as India and Indonesia, which have the highest growth in users, to support an open and free internet both domestically and internationally.

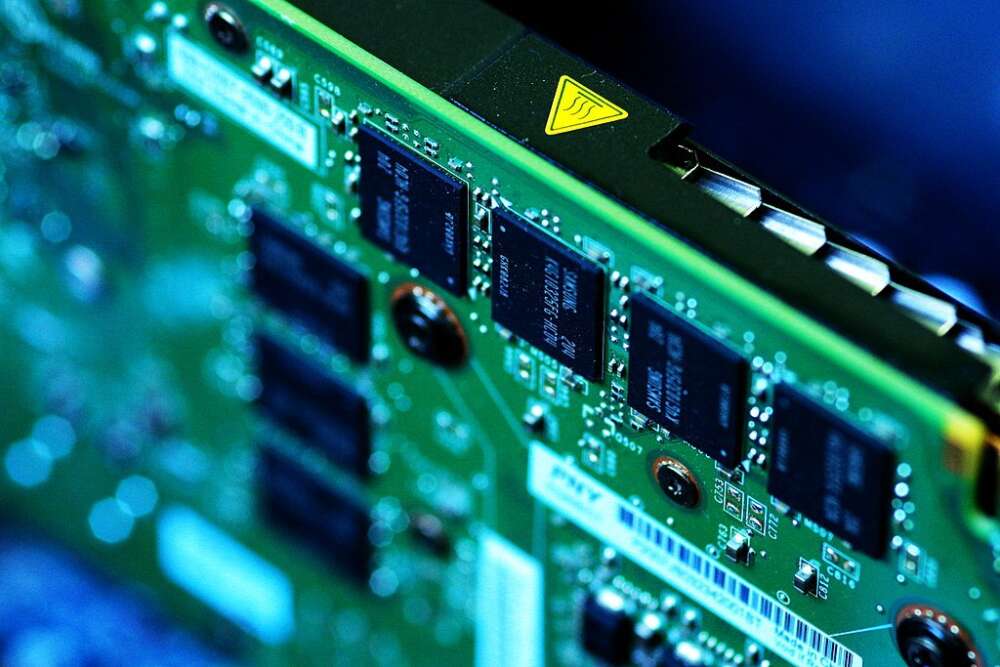

Within Europe, we need to pursue proposals that actually increase data security. This seems to be easier said than done. Most measures discussed (such as data localization and local routing; the so-called “Schengen Routing”) do not, in fact, contribute to greater data security. This is because they neglect the evidence that data privacy and security do not primarily depend on where data is stored or sent, but how data is stored and transmitted. As a result, most measures would provide a false sense of security at best. Instead, European governments should promote the responsible use of encryption; the only measure that directly contributes to greater data security of citizens, companies and the government alike.

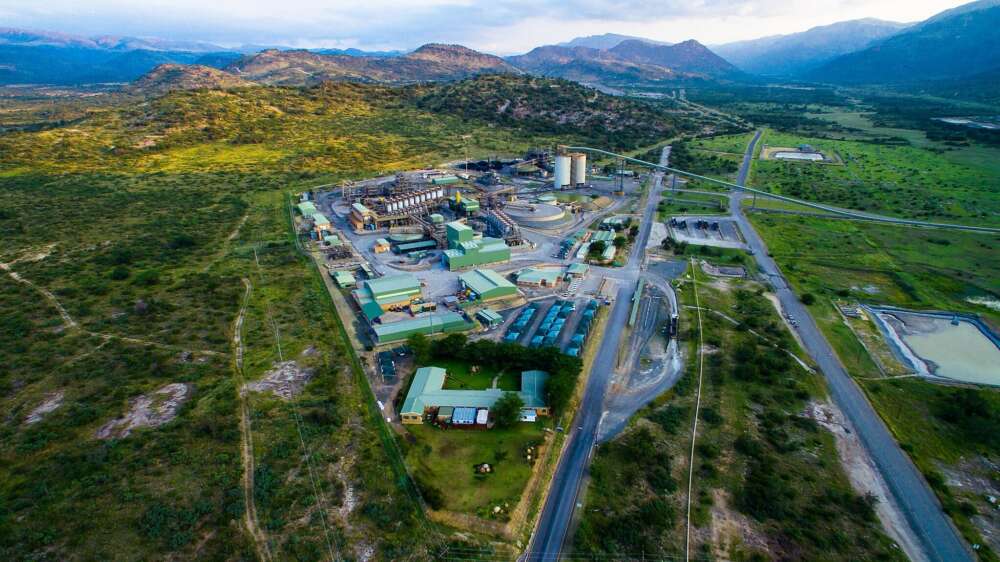

We also need to be more careful when discussing industrial policy measures. German minister for digital infrastructure Alexander Dobrindt, for example, announced with great fanfare his plan for “digital sovereignty”: “We will have to spend a lot of money on this. I remind you of the great technology offensive in the 1980s in the European air and space industry”. Creating the mythical “European IT Airbus” often invoked by policymakers is more likely to amount to investing in a white elephant that cannot fly. The digital industry is too fast moving to be conquered by a game plan inspired by the construction of the A380. Rather, we should invest in EU-wide cooperation between universities, start-ups, the military and civilian industries, with a view for Europe to catch up on “Industry 4.0”. There is a lot at stake in the debate on “technological sovereignty”. This calls for enlightenment in the original and best sense of the term, not for cozying up to the forces of digital anti-modernity.

…

A German version of this op-ed appeared in the 1 February 2015 edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.