The Awakening of the German Netizen?

As of May 2, Deutsche Telekom (DT), Germany’s former state monopolist turned stock-listed telecommunication provider, will no longer sell flat-rate Internet access packages. Users who exceed a monthly data allowance will face severe cuts to the quality of their service — in the worst case throwing them back to the stone age of the dial-up modem. DT’s own “Entertain” streaming platform will be exempted from the volume limits. Other content providers presumably could enjoy the same royal treatment — if they are willing to pay DT a little extra.

After announcing the new policy, DT ran into a firestorm of protests. CEO René Obermann faced a broad and diverse coalition ranging from Internet activists to German economics minister Philipp Rösler. The influential German blogger Sascha Lobo accused the company of “strangling the Internet.” Rösler sent a letter to Obermann expressing his concern about the threat to “net neutrality” posed by the changes that privilege DT content over other content on the web.

DT, which has come under significant pressure on the revenue side over the past years, fought back hard against the critics. The changes, the company asserts, are justified and fair: “Steadily higher bandwidths cannot not be financed by steadily lower prices.” Rather than raising rates for all costumers the new volume limits target just the small minority of heavy users comprising only three percent, says DT. 97 percent of all consumers won’t be affected.

Obermann also accuses his critics of abusing the term “net neutrality” to cement expectations of unlimited data volume and a “freebie culture” on the web. Economists support Obermann. As long as there is transparency about pricing and competition, they do not see any problem. After all, they argue, DT has clearly communicated the changes and dissatisfied users can simply switch Internet providers.

The clash of opinions about DT’s move essentially stems from divergent views of what the Internet really is all about. Obermann and the economists consider the Internet a marketplace where customers choose between service packages and companies struggle for survival (especially the major telecoms which have seen their old business model evaporate). If you accept these premises, DT’s arguments actually make sense.

However, the picture looks radically different for those who take a citizen-centric view. From this vantage point, the web is primarily a public space in which citizens should be able to express themselves freely. It is for citizens to fight for and use the freedoms of the digital commons — as “netizens.” Lawmakers and regulators should do their part to ensure a free Internet. Upholding “net neutrality” (alongside privacy and data protection) is a cornerstone of this effort. Its foundation is the conviction that all Internet traffic should be treated equally.

DT departs from this by treating its own “Entertain” service in a privileged manner ‑and opening the door to give certain content providers privileged treatment if they are willing to pay for this managed service.

For Internet freedom advocates, it is a good sign that economics minister Rösler invoked “net neutrality” in his criticism of DT’s new pricing policy. They should use this as a starting point for intensifying their campaign for enshrining network neutrality into law — not just in Germany, but EU-wide.

To see how it is done, they should look at Chile. The South American country led the way by requiring Internet service providers to “ensure access to all types of content, services or applications available on the network and offer a service that does not distinguish content, applications or services, based on the source of it or their property.” In the EU, so far only The Netherlands has a similar law in favor of net neutrality.

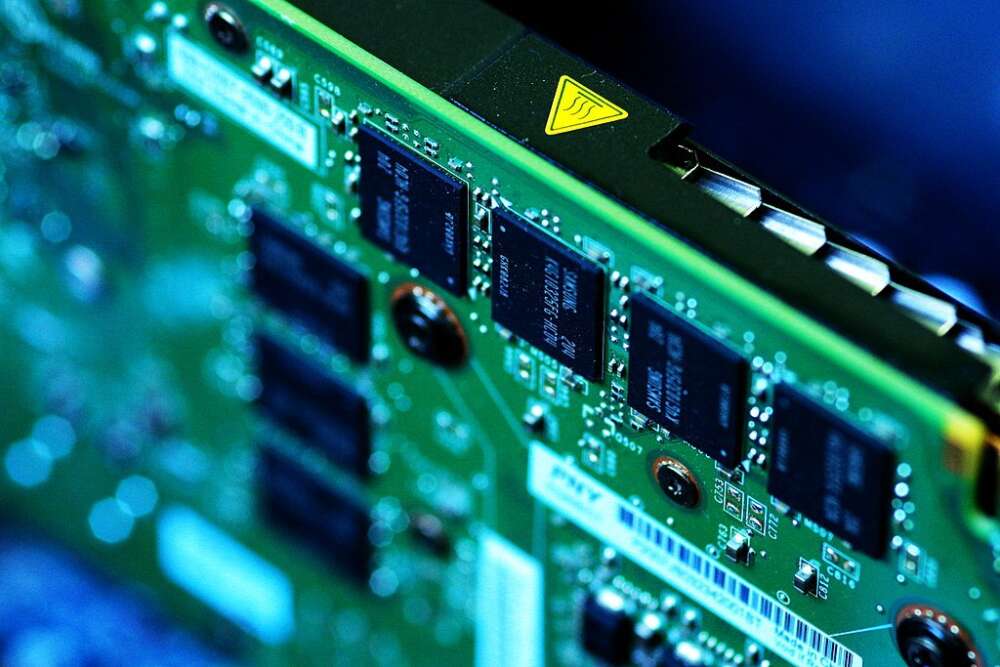

In April 2013, a coalition of 80 European digital rights and consumer NGOs argued that “in light of the many reported violations of net neutrality, it is now clear that we now need timely and evidence-based action.” In addition to enshrining net neutrality into law, this includes reporting obligations on the part of Internet service providers on network management practices, an independent monitoring authority as well as restricting the use of deep-packet inspection (network filtering system that inspects data for protocol non-compliance, viruses, intrusions and the like before letting it pass — the ed).

In Germany, advocates of digital rights and internet freedom have long been on the very margins of political power. Within most political parties, advocates of digital freedom and innovation are regularly outvoted by their opponents.

To be sure, NGOs such as “Digitale Gesellschaft” (Digital society) do excellent work. But compared to the US the movement lacks a strong professional base of full-time advocates. German foundations have invested too little in advocacy and research on digital rights and innovation.

Hopefully, the debate on DT’s move marks a turning point with Internet users increasingly realizing that they need to organize politically in order to fight for digital rights and preserve the web as a force for innovation.

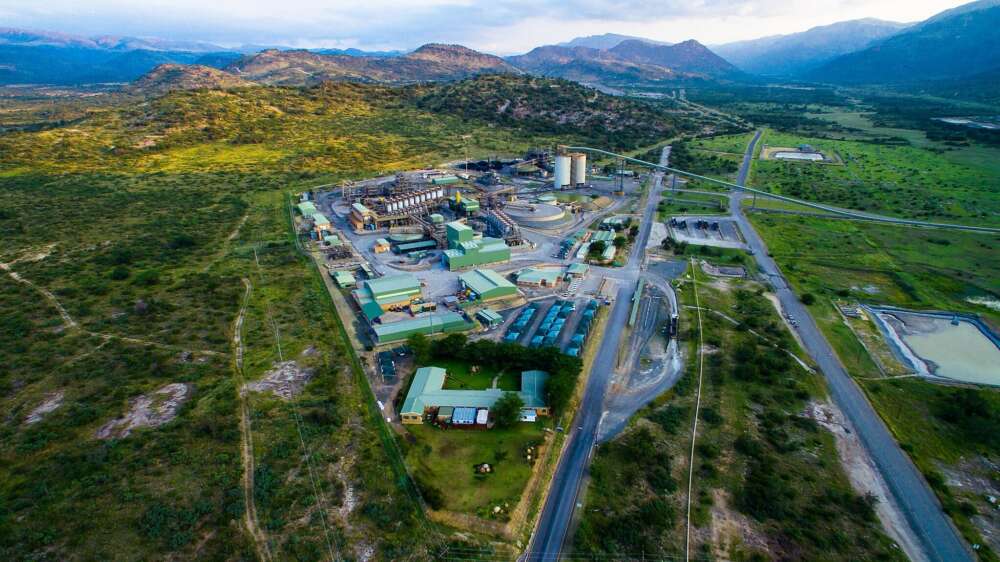

Wherever there are clear synergies between social and commercial benefits, civil society advocates should join forces with the progressive parts of business. This includes ensuring broadband Internet access and building intelligent networks infrastructure. Both require massive investments.

Minister Rösler’s so-called broadband strategy does not provide a convincing plan for the scale of the push needed. If DT’s phasing out of the flatrate spurs activists in civil society and business to successfully push for a more ambitious political agenda on digital rights and innovation, it will have served a good purpose after all.