The Dinosaurs’ Last Hurrah?

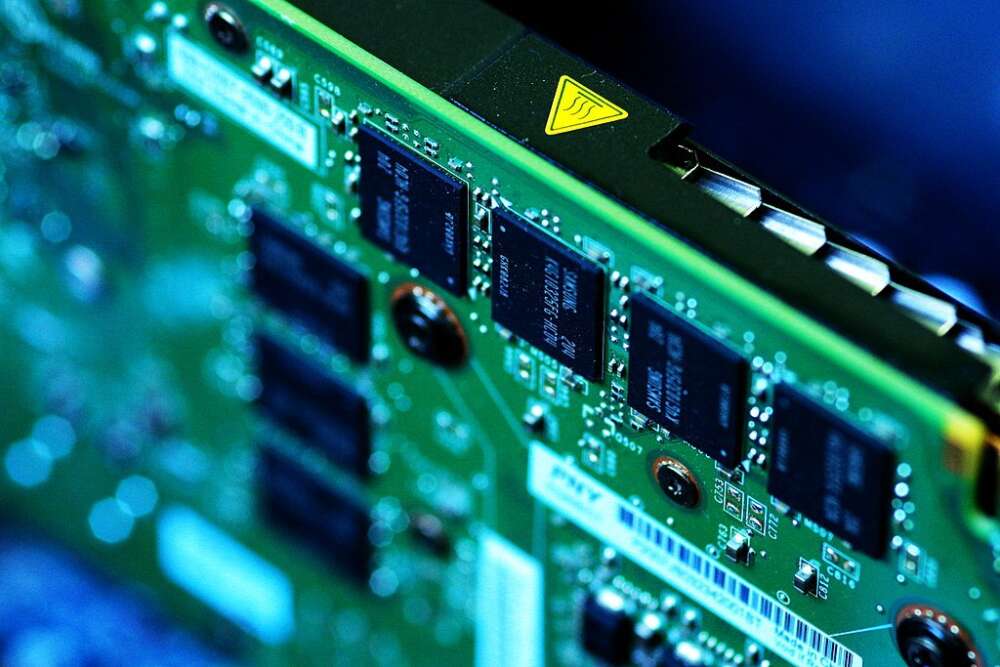

“You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.” In 1996, John Perry Barlow, the apostle of the Independence of Cyberspace, famously disinvited governments from dealing with the business of the Internet.

Now that cyberspace has developed from a hangout for the nerdy fringes to a central location of innovation, economic profits and political conflict some of the “weary giants of flesh and steel” are staging a comeback.

At the meeting of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in Dubai, countries such as Russia and China are leading the charge to reassert their sovereignty in cyberspace.

China for one has asserted that “cyber sovereignty is the natural extension of state sovereignty into cyberspace and should be respected and upheld.” Russia in a similar vein argues that “member states shall have the sovereign right to manage the Internet within their national territory, as well as to manage national Internet domain names.”

In the name of security

Both countries want to wrestle away the control of the Internet from multi-stakeholder networks such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to the intergovernmental ITU. They drape their proposals in the language of “Internet security” that is also fashionable with a number of Western policymakers.

In light of the Chinese and Russian advances, government and business representatives and other commentators in the West have been ringing the alarm bells. The Wall Street Journal for example talks about the “UN’s internet sneak attack.” These voices tend to overlook that the present efforts don’t exactly come as a surprise. The first attempt to secure a stronger role for the ITU was staged in 1996 — right when Barlow typed up his declaration of independence.

A number of other attempts have followed since — all of them failed. This time around in Dubai it is again unlikely that Russia and China will gain enough support for their idea. Even countries such as Brazil and India which until recently leaned toward a stronger role for the UN tend to show support for multi-stakeholder approaches rather than controlling the web through intergovernmental bodies.

Stifling the Net

However, given that the sovereigntist backlash has become fiercer and is unlikely to abide any time soon, it makes sense for the opponents to forcefully point to the dangers of the Russian and Chinese approach.

It would risk stifling the Internet that has thrived on being an open system not controlled by any one organization where innovators don’t need to ask governments for permission and where different stakeholders are involved in rule-making.

At the same time, it is dangerous to overlook the flaws and shortcomings of the current system. This is exactly the trap in which many US and European policymakers, business representatives and academics fall.

Negligent approach

The recent remark by Neelie Kroes, the EU’s digital agenda czar, about the current system of Internet governance “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is just one example of this negligent approach. She and others extol the virtues of the multi-stakeholder approach and wax poetically about the “ecosystem” of Internet governance.

Die Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) koordiniert die Vergabe von einmaligen Namen und Adressen im Internet. Dazu gehört die Koordination des Domain Name Systems und die Zuteilung von IP-Adressen, was auch als IANA-Funktion bezeichnet wird. Die ICANN hat ihren Hauptsitz in Los Angeles und ist in Kalifornien als Non-Profit-Organisation registriert.

In organizations such as ICANN supposedly all stakeholders are fairly represented, able to make their voices heard with decisions solely informed by reason and the better argument. It all sounds as if the Habermasian paradise of the “ideal speech situation” has finally been realized, if not on earth, then at least in cyberspace.

This is shortsighted.

Bugs in the system

Just because Russia and China are prescribing the wrong cure, does not mean that the current system does not have serious shortcomings. First, it is very much dominated by Western actors. The US is seen as wielding a particularly outsize influence. Representatives from developing countries have a hard time exercising a voice in and influencing the outcomes of multi-stakeholder processes.

ICANN which is based in California is perceived as beholden to US interests due to its proximity to Silicon Valley and through its special ties with the US Department of Commerce. This impression is fatal at a time when most of the increase in Internet users comes from outside the West using languages other than English.

It undermines the legitimacy of the current system of Internet governance at precisely the time when it is challenged by authoritarian interests. Only if the West starts to address these problems, can it hope to include countries such as Brazil and India in a stable coalition for a free and open Internet. As a first step in this direction, Europe should lobby the US to suggest a relocation of ICANN from the US to a more neutral location.

Big Brother

What’s more, the US and Europe must tend to some of the less discussed, but real dangers to a free and open Internet. Scottish journalist Ryan Gallagher in Slate points to the “increasingly centralized and homogenized international surveillance infrastructure, with more sophisticated attempts to monitor online communications and closer cooperation between states when it comes to retaining data and tracking down suspects.”

This push comes partly from the security apparatus within the West and needs to be countered. A more coherent policy for promoting “Internet freedom” on the part of the EU and US would also include a ban on exporting surveillance technologies.

Furthermore, the EU and the US should support checks and balances of digital behemoths such as Facebook in terms of privacy and user rights. Since governments alone won’t do the trick, a movement of concerned “netizens” needs to hold the wielders of digital power to account, as advocated by trailblazing US author and activist Rebecca MacKinnon.

System upgrade needed

This and not delusional satisfaction with the status quo of Internet governance should inform the actions of progressive governments, business and civil society representatives. This week, Google’s vice president and chief evangelist, Internet legend Vint Cerf, declared the efforts by Russia and others at the ITU conference as hopeless. “These persistent attempts are just evidence that this breed of dinosaurs, with their pea-sized brains, hasn’t figured out that they are dead yet, because the signal hasn’t traveled up their long necks.”

Rather than focusing on the supposedly inferior brainpower of a species and its arguments that are allegedly doomed for extinction, supporters of a free and open Internet should invest their brainpower on upgrading the existing system of Internet governance.