Ask the Experts: Lessons for Regional Stability in the Lake Chad Basin

As part of our project, Political Tools for Managing Crises in Africa, jointly implemented by the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) and the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), we have invited two experts to share their insights on the reintegration of former Boko Haram members[1] and broader transitional justice approaches in the Lake Chad Basin.

Boko Haram’s two major factions, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS), do not respect national boundaries; recruits in Cameroon and Chad often come from Nigeria and Niger, and vice versa, albeit to a lesser extent. The groups are sustained by networks and resource routes that cross multiple borders.

In response, there has been some progress in regionally connecting national kinetic approaches, most notably through the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF). However, years of worsening conflict in the Lake Chad Basin have shown how military responses will only ever constitute a partial solution to countering groups like ISWAP and JAS. MNJTF’s operations have contributed to the weakening of these groups, but have also disrupted the countries’ development, ruptured social cohesion, and created deep-seated mistrust of national governments.

Recent developments in conflict dynamics across Nigeria and the Southern parts of Niger – which have included the mass surrender of former Boko Haram combatants – have made Disengagement, Disassociation, Reintegration, and Reconciliation (DDRR) programs extremely important.[2] Yet, there has been little progress towards improving cross-border cooperation in this space and few efforts to learn from more successful models used in the region. Regional fragmentation has allowed many individuals returning from areas held by armed groups to fall through the cracks, meaning some are losing out on the reintegration support they need or receiving harsher prosecution in some areas than others.

This raises important questions: Why do DDRR initiatives in the Lake Chad Basin continue to be so fragmented, and what is the impact of these initiatives on the lasting reintegration of individuals associated with Boko Haram? What lessons can previously used approaches, including local models such as the Borno Model in Nigeria, offer the region as it confronts these challenges? Two experts address these issues below:

- Milena Berks, from the Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (bicc), highlights the lack of regional coordination in defection programs across the Lake Chad Basin, arguing that inconsistent national policies and inadequate community engagement undermine reintegration efforts, especially for women and former members of armed groups.

- Steve Amuda, from the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD-WEST AFRICA), examines Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor and the Borno Model, emphasizing their potential to manage mass surrenders through non-judicial, community-based reintegration, while warning that success depends on stronger accountability, victim inclusion, and trust-building at the community level.

Together, their contributions shed light on the need to rethink how the Lake Chad Basin approaches non-kinetic responses to violent extremism and offer guidance for building more coherent, locally grounded and regionally coordinated pathways forward.

Uncoordinated Pathways: Rethinking Defection Programs in the Lake Chad Basin

Milena Berks, Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (bicc)

Defection programs, which encourage individuals to leave armed groups, including ISWAP and JAS, still lack regional design, coordination and implementation in the Lake Chad Basin. This can have implications for where people defect. When former members of armed groups decide, for a variety of reasons, to defect, they may be more likely to do so in places where conditions are favorable, for example, where general amnesties or program benefits, like housing, food, training, and income-generating activities to support socio-economic reintegration, are available. Cameroon adopted a general amnesty, which has resulted in higher defection numbers than in Chad. The latter has not established a general amnesty or a formal program to support those defecting. In Chad, many of those returning from armed groups have self-demobilized, meaning they have returned directly to communities without any formal support from the authorities or other actors.

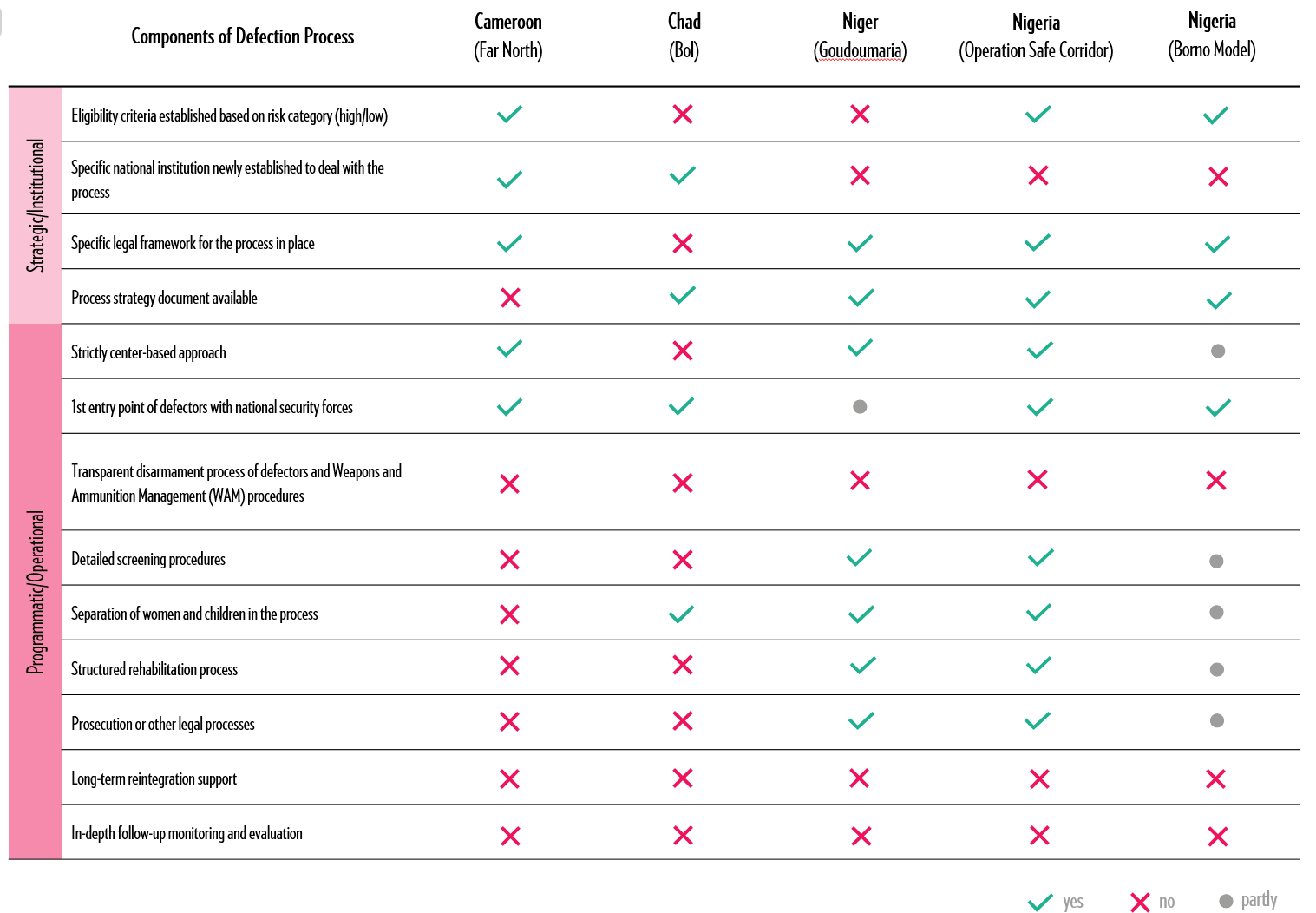

Unfortunately, as the bicc team found in a large regional study into different approaches to defection programming across the Lake Chad Basin, despite common efforts by the Lake Chad Basin Commission, such as establishing the Regional Stabilization Strategy, national-level efforts remain scattered and fail to reach their potential. Across Lake Chad Basin countries, defection programs vary significantly, which impacts their long-term effectiveness (see Table 1).

Table 1: Components of defection processes in LCB countries (Source: Berks et al. (2025). Maximising Impact of Defection Programming in the Lake Chad Basin. Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies. p.15.)

Former members of armed groups often face severe psycho-social challenges, and many suffer from trauma, drug abuse or sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Failing to support defectors in addressing these challenges has significant implications for their long-term prospects of reintegration and broader reconciliation efforts with communities. This is especially true for gender specific needs; women and girls are insufficiently considered within defection programs and need to be supported more consistently.

Formalized defection programming, including rehabilitation support and training, increases the likelihood that former members of armed groups will successfully reintegrate into their communities. In countries with formalized processes, such as Nigeria, more than 80 percent of respondents in the bicc regional study thought that DDRR processes should be strengthened. The opposite was true in countries where processes were not formalized, or were less formalized, or showed deficiencies.

Yet when it comes to reintegration prospects, formalization does not necessarily result in better outcomes. When reintegration efforts do not benefit communities, they can (and have) provoked resistance and generated a sense of grievance from community members about the integration of former militants (back) into their midst. While respondents in Nigeria frequently pointed out how “those coming out of Operation Safe Corridor [a Nigerian government program aimed at disarming, demobilizing, and reintegrating former Boko Haram members into society] are better behaved” than those who did not go through it – for instance under the Borno Model – the overall approval rates for the program remained low. Over 30 percent of respondents (in a survey bicc conducted in 2023 and 2024 in Cameroon, Chad, and Nigeria) indicated that the primary challenge to (re)integrating former members of armed groups was communities not wanting them back. More than 20 percent (and up to 30 percent in Chad) believed that those associated with armed groups were a security risk.

To make defection programming more effective, it is key to consider community perspectives from the outset and integrate those into current programming, including identifying prospects for peaceful coexistence and potential reconciliation.

Towards Peace in the Lake Chad Basin: Regional Approaches to Boko Haram Reintegration and Transitional Justice

Steve Amuda, Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD-WEST AFRICA)

In 2016, the Nigerian government introduced Operation Safe Corridor to create an opportunity for Boko Haram members to surrender, demobilize, disassociate, and reintegrate into the larger society. Despite the initiative’s successes, it has been criticized for a poor human rights record and for a failure to properly engage with communities that those associated with armed groups return to.

Borno State, which has long been the epicenter of the conflict, also introduced a local approach, called the Borno Model, initially as a spontaneous arrangement to receive and manage mass exits from Boko Haram following the death of leader Abubakar Shekau in 2021. Building on the initial exodus, and with support from various stakeholders (including the UNDP), Borno State has used dialogue and mass media campaigns, as well as targeted communications, to persuade Boko Haram/ISWAP members to embrace peace, laying down their arms to national troops at the various reception centers.

The program strives to address and overcome the gaps identified in Operation Safe Corridor by moving away from securitized approaches and fostering greater community participation through a more inclusive and effective methodology. It avoids the use of controversial facilities like the Joint Investigation Centre at Giwa Barracks, where arbitrary detentions and abusive interrogation techniques have been extensively documented. It facilitates more regular and sustained communication between communities and those returning from Boko Haram held areas. The model centers the transitional justice system, adopting reintegration and reconciliation of victims and perpetrators through non-judicial means.

The successful progress of the Borno Model hinges on its ability to reintegrate former perpetrators back into communities to cohabit peacefully and productively with victims of Boko Haram. So far, the model has struggled with accountability and restorative justice measures, which have led to resentment on the part of victims and the communities. There is a trust deficit between ex-associates of Boko Haram and community members, broken social cohesion caused by years of violence, and a lack of strategic communication on the part of the Borno State. Communities often raised concerns that their grievances and needs were not properly considered in the implementation of programs like the Borno Model. The lack of a clearly outlined and practically functional reintegration strategy leads to the fear of community retribution.

Governments across the Lake Chad Basin should adopt a policy framework that ensures the inclusion of communities and victims of the insurgency in the process of reintegration. Sustainable reintegration of defectors should be locally owned; community-based participation could facilitate greater social acceptance of former members of armed groups, build trust, and foster social cohesion. This should include strengthening the capacity of traditional and religious leaders.

Towards Locally Anchored, Regionally Coherent Reintegration

Taken together, these two contributions highlight the difficulty many countries in the Lake Chad Basin have had in developing effective programs for reintegrating former associates of armed groups. Although defection programs exist across the region, their disparate and uncoordinated nature limits their effectiveness. Even Nigeria, which has developed much more formalized and advanced systems than some of its neighbors (such as Chad), struggles to deliver on a sustainable disengagement pathway for former associates of armed groups (and the communities that they eventually live amidst). While more recent models, like the Borno Model, have gone a long way in addressing the failures of securitized approaches of the past, they too struggle with community acceptance and with delivering clear, actionable frameworks.

Both contributions offer clear guidance for national and local governments seeking to improve systems for disarming and reintegrating former members of armed groups. First, these initiatives must focus on community engagement from the outset, recognizing the role of local actors in facilitating acceptance and the prospects for reconciliation. This engagement must include providing social and public goods to the community – not just to former associates of armed groups – to limit grievances and improve the acceptance rate of these programs. Second, these initiatives must be practical, clear and accountable. Third, these initiatives must address the psychosocial and gender-specific needs of former associates of armed groups to foster durable reintegration. A holistic approach rooted in these principles would be a good basis for regional approaches providing a lasting pathway to the sustainable reintegration of former Boko Haram members.

Our project will continue to explore these issues through additional research and policy engagement, including an upcoming policy brief focused on what lessons the Borno Model offers the wider Lake Chad Basin.

These contributions were collated by Abi Watson (GPPi) and Taiwo Adebayo, an ISS researcher based in Abuja (Nigeria).

Please note: The opinions expressed by the authors are their own and do not reflect the official positions of GPPi, ISS or any affiliated organizations.

[1] Terms “ex-combatant” and “former associate” have important differences as they refer to the different levels of engagement within armed groups designated as terrorist organizations, which has direct legal implications for the individuals concerned. While “ex-combatant” implies an active role within the group that is subject to prosecution in the absence of other legal provisions, “former associate” refers to a person who was previously associated with an armed group. The determination of association and ex-association is contingent on a screening process. This is discussed much more extensively here: https://www.bicc.de/Publications/Report/Maximising-Impact-of-Defection-Programming-in-the – Lake-Chad-Basin/pu/14863

[2] Disengagement, Disassociation, Reintegration and Reconciliation (DDRR) approaches recognise that in contexts of violent extremism, one or more of the preconditions for disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) are missing, that is, the signing of a ceasefire or peace agreement, confidence in the peace process, willingness of the parties to the conflict to engage in DDR and minimum security guarantees for the implementation of a DDR programme. This is discussed much more extensively here: https://www.bicc.de/Publications/Report/Maximising-Impact-of-Defection-Programming-in-the – Lake-Chad-Basin/pu/14863