Space – Flows – Rules: Securing the Commons in a Network Order

Revisiting Haushofer’s Ghost

In 2025, maps (still) shape incentives, but they no longer dictate outcomes. Power travels not only through straits and passes, but along supply chains, data cables, payment rails, and technical standards – and is bounded by power‑backed rules that raise the cost of coercion. This essay keeps Karl Haushofer’s map, where geopolitics still matters, while discarding his original myth that geography is everything. Instead: geography frames, connectivity scripts and power‑backed rules decide.

Chapter 1. Maps Set the Stage, Networks Write the Script

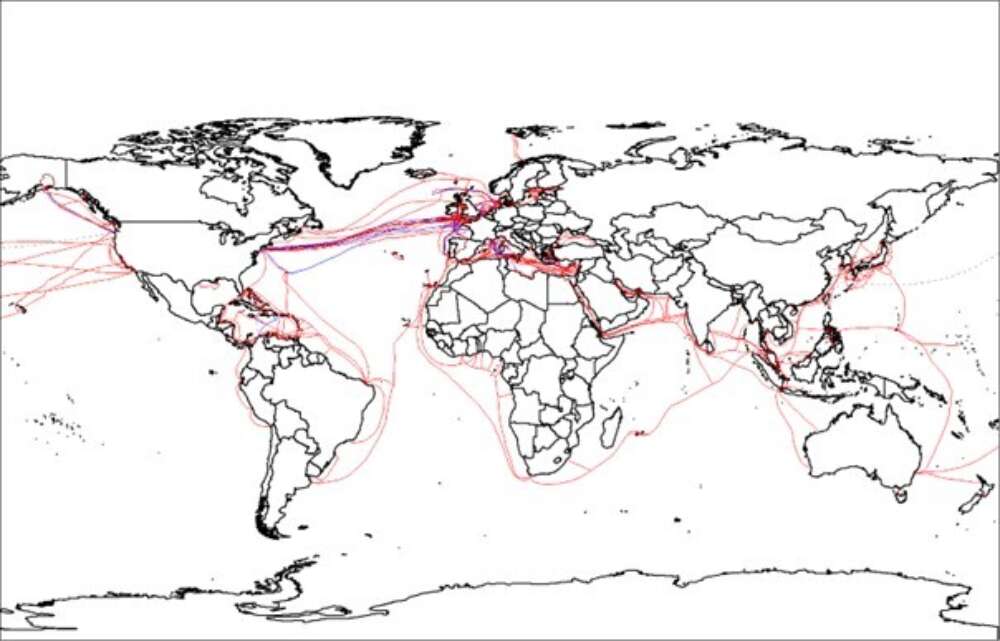

On a clear August morning in 2023, Russian Kalibr missiles slammed into the grain terminals of Odesa, snarling Ukraine’s Black Sea exports. A thousand miles away, an explosive drone launched by Houthi rebels shuttled toward a tanker in early July 2025, briefly spiking naval insurance rates, as shippers contemplated detours around the African continent. Meanwhile, far from any battlefield, engineers in hazmat suits were quietly shaping the balance of power at Taiwan’s chip foundries, responsible for producing over 90 percent of the world’s most advanced semiconductors. Today, power moves along straits and passes, but it also runs through supply chains, data cables, payment rails, and technical standards.

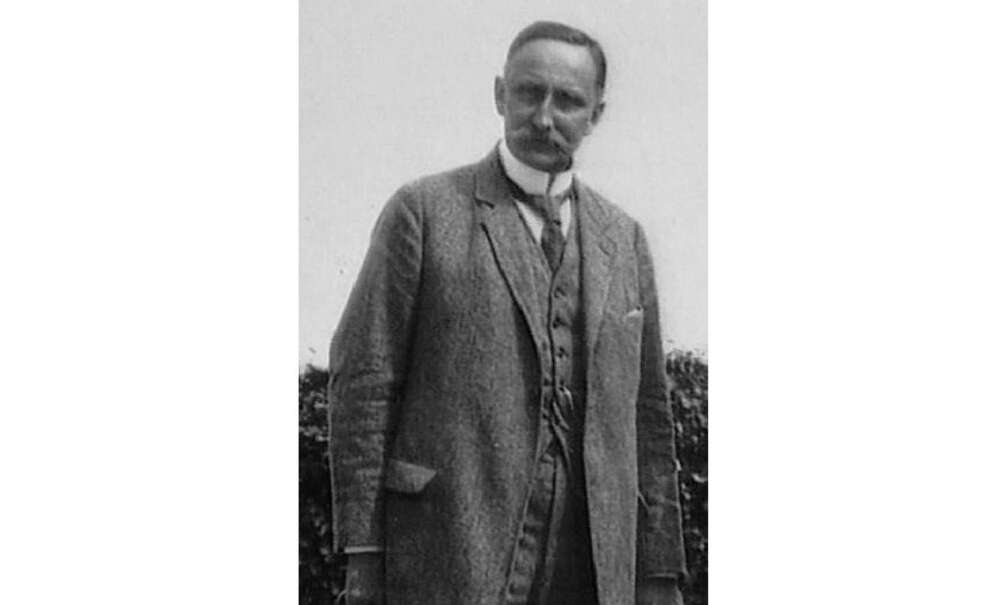

This essay seeks to revisit German general-turned-geographer Karl Haushofer’s (1869−1946) notion of Geopolitik, firmly distancing itself from the dark ways in which this concept was twisted and Haushofer’s zero-sum, pseudo-Darwinian interpretation of the world, while keeping other elements and viewing Haushofer’s map as a useful analytical lens. How would Karl Haushofer view our current landscape of power? Would he even recognize the map? This piece argues that he would – power still matters – but that we need to reconsider and re-weigh certain elements he fundamentally underestimated.

Old maps seem to speak again. Karl Haushofer would recognize the stage – land and sea, corridors and chokepoints, buffers and depth – but he would misread the script. Unlike in his day and age, geography no longer decides (though it still frames). Today, straits like the Bosphorus or the Hormuz (in the Persian Gulf) matter, but so do fiber‑optic cable landings and semiconductor fabs. A coastal port can be blockaded, but a nation’s internet can also be throttled by cutting undersea cables or denying satellite access. Vulnerabilities are not merely physical chokepoints – they include the “panopticon” side of interdependence: surveillance, espionage, and data exfiltration that coerce without kinetic disruption.

In short, maps set the stage, connectivity writes the script, and power‑backed rules referee and, at times, decide the outcome.

This essay offers a way to use Haushofer without being used by him. We can return to his classical geopolitical categories, treating them as organizing concepts (space, resources, lines of communication), while rejecting the determinism and imperial ambitions that discredited Haushofer’s school. My approach is to test today’s crises against a broader analytical framework – one that accounts for space, flows and rules – and to derive policy responses that secure connectivity (through layered, polycentric governance, credible deterrence by denial and punishment, and enforceable minilateral coalitions), reduce overdependence, and compete in connectivity and standards without sliding back into carved‑up “spheres” of influence. The goal is a fluid, network‑aware grand strategy: academically grounded, frank about power and enforcement, and cognizant of the fact that maps matter, but they do not rule outcomes.

Chapter 2. Keep the Lens, Drop the Dogma

Karl Haushofer’s interwar Geopolitik fused strands from Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén, Halford Mackinder, and Alfred Thayer Mahan into an applied political geography with a determinist cast. He imagined a world of Pan-regions: quasi‑autarkic continental blocs vying for self‑sufficiency, strategy as a contest between land and sea power, and chokepoints as hinges of fate. Any wholesale “revival” of this doctrine is discredited by its instrumentalization under National Socialism – most infamously the racialized misuse of Lebensraum – which cherry‑picked and radicalized parts of the vocabulary to justify expansion and worse. What remains usable is a lens, not a law.

Two categories survive as organizing concepts. Raum names spatial conditions – depth, distance, terrain – that structure opportunity and risk in war and statecraft. Verkehr denotes lines of communication – routes, bases, and bottlenecks – that move power across space, including the sensors, repair capacity, and standards that govern them. Taken together, they discipline analysis by reminding us that location imposes constraints and that logistics are political. Yet neither category warrants determinism. Raum frames problems but does not decide outcomes; technology, organizations and institutions mediate what geography permits. Verkehr elevates logistics to strategy: railways, ports, canals, straits, air corridors, undersea cables, and satellites are levers of power. Control and denial along these networks can offset positional disadvantage and amplify coalition reach.

A compact genealogy situates this lens. Ratzel coined Lebensraum as a biological metaphor later distorted in policy; Kjellén coined Geopolitik; Mackinder linked continental primacy to a Eurasian “Heartland”; Mahan made command of sea lanes central. Haushofer popularized these vocabularies – via the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, amongst others – by recasting strategy as securing space and controlling flows. That genealogy is instructive precisely because it marks what to keep and what to drop.

What we drop is the dogma: determinism, the autarkic illusion of Pan‑regions and organic metaphors that erase small‑state agency. In a networked economy, autarky is brittle and uneconomic; resilience arises from diversified interdependence with trusted partners, not from fortress blocs.

This pruning clarifies the bridge to the framework developed below. Space still frames incentives; flows redistribute leverage across and beyond that space; and rules convert network position into power when – and only when – backed by capabilities, market leverage, credible attribution, and enforceable coalitions.

In short: keep the map, drop the myth.

Chapter 3. Space, Flows, Rules – Under Moving Maps

To create a usable framework for the twenty-first century, we need to combine Haushofer’s spatial lens with three additional forces he underweighted – and a fourth he could not have foreseen. The framework rests on four axioms: (1) space still frames incentives; (2) flows redistribute leverage; (3) rules can temper raw coercion when backed by capabilities, market leverage and enforceable coalitions; and (4) technology/climate are shifting the geometry itself.

(1) Space still frames incentives. Geography (still) poses enduring strategic dilemmas that leaders must solve. From the Black Sea to the Malacca Strait in Southeast Asia, physical terrain continues to set the parameters of conflict and commerce. No amount of technological progress has repealed the fact that seizing a narrow strait can throttle trade: one-fifth of global oil passes through Hormuz, and China still faces its “Malacca dilemma” (over 80 percent of China’s crude imports transit the Malacca Strait). Being landlocked or lacking strategic depth remains a vulnerability for nations – consider how Ukraine’s flat steppe offered invaders a broad front. Meanwhile, countries like Türkiye or Egypt can leverage their control of strategic waterways (the Bosphorus, the Suez) for diplomatic influence. In short, geography still sets problems that strategy must solve, even if it no longer provides all the answers.

(2) Flows redistribute leverage across (and beyond) that space. In today’s hyperconnected world, power travels not only with tanks and ships, but along supply chains, fiber‑optic cables, satellite constellations, logistics networks and the plumbing of finance. These networks can bypass, magnify or weaponize geography. A deep‑water port still matters; so does the cable landing station that brings a region online. A mountain pass can shape a battle, but so can control over a software stack or a payments network like SWIFT.

States now systematically exploit these interdependencies. As Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman argue, “weaponized interdependence” works through chokepoints (controlling critical nodes to exclude others) and panopticon effects (using centrality in networks to see and thus influence behavior). In such a system, pivotal nodes – from high‑tech sensors to banking and data infrastructure – become instruments of coercion. We see this in practice: US‑led restrictions on advanced semiconductors and access to SWIFT have constrained Russia’s ability to obtain precision components and finance its war effort.

By contrast, panopticon leverage arises where network centrality confers visibility and pressure without overt disruption – through cloud platforms, app distribution, satellite telemetry, or data‑rich telecom backbones. Beijing and Washington alike understand that commanding supply‑chain chokepoints (rare‑earth processing, high‑end lithography) yields strategic leverage. Connectivity creates new chokepoints absent from old maps: the concentration of cutting‑edge chip fabrication in Taiwan functions as a non‑territorial chokepoint for the global economy.

A second lever is visibility into flows: control over cloud‑ and satellite‑based sensors, telecom equipment and data standards confers panopticon capacity that can coerce, short of kinetic attack. Control over flows and networks can match – and sometimes exceed – the power of holding territory, but only when attribution is credible (i.e., responsibility for attacks can be assigned and explained with high confidence), legal levers exist and coalitions are prepared to impose costs. Where those conditions are absent, territorial control still yields blunt leverage.

(3) Rules and standards convert network position into power – when backed by capabilities, market leverage, and enforceable coalitions – and they can temper raw coercion. Legal and normative regimes, from payment systems to technical standards, allow states – especially liberal democracies – to shape choices at a distance, but only when attribution is credible and compliance‑and‑sanction pathways exist.

Multilateral sanctions and compliance systems can financially isolate aggressors – witness the EU and G7 partners’ push to remove major Russian banks from SWIFT and restrict high‑tech imports – raising the long‑term costs of the war in Ukraine. Targeted export controls on advanced technologies – led by the United States, the EU, Japan and others in the semiconductor domain – likewise show how standards and licensing can constrain a rival’s ascent.

International law and institutions also raise the reputational and economic price of territorial adventurism when violations can be attributed and collectively penalized. When Turkey invoked the 1936 Montreux Convention in 2022 to close the Straits to belligerent warships, it limited Russia’s naval movements in the Black Sea – evidence that treaties can bind even great powers. Maritime law (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS) and straits regimes do not prevent every breach, but they furnish the legal footing for diplomatic pushback, collective pressure and coalition‑based enforcement. By upholding principles such as freedom of navigation and exclusive economic zones, broad – if heterogeneous – enforcement coalitions signal that aggressive faits accomplis will not be cost‑free.

Put simply: rules backed by power mediate geography. A century ago, might made right; today, norm‑breaking invites sanctions and stigma – unevenly and often slowly. Whether a state (or cluster of states) can deter such rule‑breaking depends on coalition breadth, market share and legal venue. Linked to capabilities and market leverage, rules become instruments of statecraft in their own right. States deeply integrated into a rules‑based order and enforcement coalitions attract capital, talent and partners through predictability and legitimacy; those who flout the rules court technological isolation and economic shunning.

(4) Technology and climate are shifting geometry itself. Strategic geography is no longer static. Technical innovation and planetary changes are redrawing maps once thought fixed – not a factor Haushofer could have possibly included in his vision of geopolitics. The proliferation of precision‑strike weapons blurs the boundary between land and sea power; cyber tools and commercial satellite constellations ignore borders entirely.

At the same time, climate change is altering our shared physical reality, with great strategic effect. Drought, predicted to increase with global warming, has periodically choked traffic through the Panama Canal and Europe’s Rhine. Warming Arctic seas are opening new maritime passages across the far – historically frozen – north. These arctic shortcuts could cut Europe‑Asia transit distances dramatically, yet positional advantage is not automatic: it depends on enabling capacity (icebreakers, search‑and‑rescue infrastructure, insurability) as well as on legal clarity. In short, technology and climate are introducing variables and vulnerabilities classical geopolitics scarcely considered. The map is moving under our feet.

Synthesis – A Practical Maxim: Interdependence Without Overdependence

When triangulating space, flows and rules to secure our position, the objective is not autarky, but rather deliberate redundancy and diversification at critical nodes, built with allies. No single supplier, route or technical standard should be able to hold the system ransom. This logic underpins the shift toward de‑risking from China (rather than wholesale decoupling). The United States and its allies are adopting a similar posture in sensitive sectors – onshoring or ally‑shoring the most vital supply chains – while keeping trade open where risks are lower. Resilience, from this perspective, is characterized by switch time (how quickly supply routes and sources can be reconfigured), coalition depth, path diversity and the average time it takes to restore critical nodes – not by the mirage of total self‑sufficiency.

Recent analyses underscore the folly of autarky: building fully self‑sufficient semiconductor ecosystems in each major region would be economically untenable and duplicative. The feasible path is open interdependence with guardrails and backups: stockpiling critical materials, diversifying import sources, investing in allied capacity, and tailoring export controls to the few technologies that are truly decisive in geopolitics.

The guiding principle is simple: eliminate single points of failure. Properly structured, interdependence binds economies into a positive‑sum web where the whole exceeds the parts.

In the next section, three geopolitical theaters test this maxim in practice.

Chapter 4. Three Theaters, One Policy Lesson: Secure the Commons

One danger looms large: if an actor can monopolize a critical node, interdependence becomes a lever of coercion. This essay will now consider three current strategic theaters to demonstrate this dynamic: (1) Ukraine and the Black Sea, (2) Taiwan and the “Silicon Strait” and (3) the corridors from the Red Sea to the Arctic. Each example illustrates how geography sets the stage, but flows and rules increasingly write the script. Across the board, one policy lesson becomes clear: secure the commons and the “connective tissue,” not new empires.

Ukraine & the Black Sea: Arm the Map, Secure the Flows

A map‑forward lens on Russia’s war against Ukraine highlights the old hardware of geopolitics – depth across a flat frontier, Crimea’s leverage over the Black Sea, Türkiye’s treaty‑based control of the Straits under the Montreux Convention. Those facts still matter. But Ukraine’s endurance has rested just as much on networks and rules as on terrain and troops.

When the Black Sea Fleet tried to choke Ukraine’s seaborne trade, Kyiv shifted exports to rail and the Danube. In parallel, shared Western intelligence and long‑range precision weapons shortened Ukraine’s “kill chain” (the time from detection to strike): domestically adapted sea drones and anti‑ship missiles, cued by allied ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) hit Russian naval assets and made an amphibious assault implausible. Sanctions and export controls tightened access to finance and precision components, forcing costly improvisation in Russia’s defense industry. Law mattered, too: Ankara’s faithful application of Montreux in 2022 kept additional Russian warships out of the Black Sea. UN diplomacy and tailored insurance arrangements kept some grain moving despite the threat.

Space set the problem; flows and rules helped blunt it. Ukraine needs tanks, missiles, and brigades – but also secure corridors, resilient networks, and norms that are actually upheld.

A practical way to tie these pieces together is a “Black Sea commons” strategy with a single aim: keep Ukraine connected to the world. That means persistent coastal defense and de‑mining so ports and sea lanes stay usable; integrated air‑ and missile‑defenses to protect ports and river nodes from UAVs and missiles; and reliable risk‑sharing (e.g., public insurance backstops or guarantees) so commercial shipping does not fold after each strike. It also means steady coordination with Ankara so the Straits regime functions as an instrument of stability, not a bargaining chip.

This vision now has an institutional anchor. In May 2025, the EU outlined a Black Sea strategy with a “Maritime Security Hub” to enhance situational awareness “from space to seabed,” coordinate de‑mining, and protect critical maritime infrastructure, alongside Global Gateway investments to harden ports, the Danube and cross‑border links, and renewed cooperation with Türkiye against Russia’s shadow fleet (sanctions‑evading tankers).

The basic point is simple: an open, rules‑based Black Sea serves everyone’s long‑term interest. Ukraine’s economic resilience – its capacity to export, import, and finance itself under fire – is deterrence by endurance. If Moscow concludes that Ukraine cannot be strangled into surrender, bombardment and blockade lose value.

By mid‑2023, alternative routes were robust enough that renewed Russian obstruction did not cause systemic collapse: grain kept moving via the Danube and rail, with only moderate price effects. According to the European Commission, the EU – Ukraine “Solidarity Lanes” have moved roughly €236 billion in trade since May 2022, with more than €2 billion mobilized to scale them – yet Russian attacks still raise insurance costs and depress investment, underscoring the need to modernize and harden these corridors.

The lesson is clear: empower the networks and norms that make a beleaguered nation sustainable. Arm the map – and secure the flows.

Taiwan: The “Silicon Strait”

Taiwan is a textbook island linchpin: the keystone of the first island chain, bottling up a rising continental power and anchoring a maritime cordon. Its position complicates China’s access to the Pacific and sits astride sea lanes that carry trillions in trade. Sea‑denial capabilities (coastal anti‑ship missiles, submarines, smart mines), contested airspace, island‑based missiles and nearby allied bases (Okinawa, Guam) remain central to deterring an assault.

Taiwan’s decisive weight in 2025, however, lies as much in its foundries as in its fortifications. The island hosts the world’s most advanced semiconductor manufacturing – above all TSMC – and fabricates roughly 90 percent of the highest‑end logic chips. Designs from a handful of largely US‑based firms are produced using equipment from a single Dutch supplier, ASML, the sole provider of extreme‑ultraviolet (EUV) lithography. This concentration creates a non‑territorial chokepoint: a disruption would cascade through the global economy and unsettle the military balance. Western defense systems depend on these chips; so does China’s tech sector. This “silicon shield” raises the stakes for all sides and gives Taipei distinctive leverage.

Deterrence in the Taiwan Strait therefore rests on two pillars. First, military denial. Make invasion or coercion prohibitively costly and likely to fail. Concretely, this means: stockpile munitions and fuel, harden runways, power and command nodes against missile strikes, and deploy mobile coastal batteries that can fire and relocate quickly (“shoot‑and‑scoot”). Prepare for dispersed, resilient operations so no decapitation strike can paralyze the island. Coalition maritime posture should favor denial – submarines, unmanned systems and agile, survivable forces – over symbolic “show‑the‑flag” presence that is ill‑suited to a high‑intensity fight. Recent analyses consistently underscore asymmetric defense as Taiwan’s best bet against a larger attacker.

The second leg of deterrence should be industrial and economic deterrence. Harden fabs (fabrication plants where silicon wafers become chips) and their utilities against sabotage or strikes. Secure the upstream chip stack – Electronic Design Automation (EDA) tools, specialty materials, EUV lithography – through export controls, counter‑intelligence and physical security. Distribute selected nodes of capacity across trusted partners so allies can absorb shocks and provide surge capacity (additional output that can be brought online quickly in a crisis). Ongoing projects in the United States, Japan and Europe to build advanced fabs with Taiwanese participation create redundancy and crisis‑response options.

Signaling matters as much as structure. Any adversary should expect that seizing Taiwan’s chip infrastructure by force would be a Pyrrhic victory – the facilities would likely be damaged, while coordinated export controls and technology denial would trigger long‑term isolation.

In practical terms, treat semiconductors as sea lines of communication (SLOCs): they require escorts (aligned export‑control regimes), redundancy (allied capacity) and rules (norms against targeting civilian industrial infrastructure). Reinforcing both the military and economic dimensions of Taiwan’s security acknowledges that in this theater, connectivity to the global economy is as consequential as geography.

Taiwan’s role as the world’s semiconductor linchpin ensures that any conflict would reverberate globally. Properly signalled, that fact is itself a deterrent: coercion would nullify the very gains Beijing seeks, yielding ruin and isolation – far from the tidy win‑lose calculus of classical geopolitics.

From the Red Sea to the Arctic: Governing Corridors

For our third theater, consider two corridors: the Red Sea-Suez route linking Europe and Asia, and the emerging Arctic Northern Sea Route (NSR). Both show that position still matters, but that its value now hinges on governance, technology and shared stewardship.

The Red Sea and Suez have long been a classic chokepoint pair – narrow waterways where a single incident can have outsized effects. The world was roughly reminded of this in 2021, when the Ever Given container ship got stuck in the Canal, halting roughly $9 – 10 billion in daily trade for nearly a week. In recent years, non‑state actors have exposed this corridor’s vulnerability. In July 2018, Houthi forces struck two Saudi tankers near Bab al‑Mandeb, prompting a temporary halt to shipments and a spike in insurance premiums, as some traffic detoured around the Cape of Good Hope.

More recently, during Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza (since late 2023), drones and missiles have targeted ships in the Red Sea, periodically spiking fears of major disruption along a route that carries roughly 12 percent of global trade. Yet commerce has not collapsed. Instead, a form of networked resilience has kept the route open: collective naval presence, convoy coordination and dynamic insurance pricing have sustained traffic – at higher risk and cost, but without a systemic stop. Multinational coalitions such as the Combined Maritime Forces expanded patrols and escorts, while shippers adjusted transit timing and hardened their vessels. In essence, ad hoc adaptations preserved flow through a fragile corridor.

Now look north. Climate change is thinning Arctic sea ice, tempting some to view the NSR along Russia’s Siberian coast as a future Suez alternative. Such a route would save ships a significant distance: a Rotterdam – Yokohama voyage might be nearly 10,000 kilometers shorter via the NSR than via Suez, in theory cutting transit time dramatically. The reality is more complex. Costs, safety risks and legal ambiguity remain high. Even in the summer, ships require reinforced hulls or an icebreaker escort. The weather is harsh, and search‑and‑rescue (SAR) capacity is sparse. Insurers are wary, pricing policies steeply, given limited historical data and the prospect of catastrophic losses in remote waters. Governance is unsettled as well: Moscow treats much of the NSR as internal waters, while other states regard it as an international strait – an unresolved dispute with implications for fees, oversight and access.

As a result, true transit traffic (Asia – Europe) remains limited. Although Russia touted record NSR volumes in 2023 (roughly 36 million tons, largely domestic hydrocarbons), sanctions and uncertainty have made many shippers cautious of the route. The broader lesson is straightforward: geography’s value is conditional. A route must be rendered reliably navigable and governable through technology (ice‑capable ships, satellite communications), insurance and data (to price and mitigate risk) and clear legal regimes (so sailors and investors know which rules apply).

The policy implication across both waterways is the same: move from episodic crisis response to proactive corridor governance. Whether a warm chokepoint or a frozen frontier, the aim should be establishing a resilient commons rather than securing specific leverage points for any single power. In practice, that means setting up standing information‑sharing and coordination mechanisms for key corridors – for example, a permanent Red Sea maritime security forum bringing littoral states (those states connected to a specific waterway) and major users together to share real‑time threat intelligence on piracy, drones and mines. It means institutionalizing de‑mining and rapid‑repair capabilities. The Black Sea Mine Countermeasures Task Group, launched by Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania in 2024, offers a model of littoral cooperation that could be adapted for the Red Sea and major Indo‑Pacific sea lanes. It would also entail hardening the often‑overlooked “connective tissue”: undersea cables. Multiple critical internet cables traverse the Red Sea and Mediterranean. The related vulnerabilities became clear in 2008, when simultaneous cuts near Egypt caused widespread disruptions from the Middle East to India. To protect the globe’s connective tissue, then, corridor security must include cable monitoring, redundant pathways and ready repair capacity.

Finally, sustained legal clarity is essential to disincentivize opportunism, without turning commons into exclusive spheres. In the Arctic, a broad coalition of Arctic states, key maritime users and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) should affirm – through International Maritime Organization standards and Arctic governance arrangements – that the NSR will be open to all, and on equal terms. The more they are able to strengthen this commitment, the less tempting it becomes for any one state to “capture” the route.

Conversely, attempts to dominate a corridor should meet unified legal pushback, including arbitral rulings and freedom‑of‑navigation operations. The guiding norm is straightforward: treat major corridors as global commons to be cooperatively governed for reliable passage, not as prizes to be carved into private zones of control.

Chapter 5. Where Classical Geopolitics Misleads

This synthesis of maps and networks helps explain why a purely classical, “Haushoferian” approach is misleading in today’s world. Treating cartography as a set absolute obscures agency, technology and institutions – and invites at least four distinct hazards.

First: the determinism trap. Treating geography as fate is hazardous: agency, innovation and contingency routinely upend cartographic “prophecies.” Small states and non‑state actors now punch above their weight in ways terrain alone cannot predict. Hezbollah’s 2006 strike on an Israeli corvette with an advanced anti‑ship missile showed that even an actor without a navy can contest sea control if it masters the right capabilities. In 2020, Azerbaijan’s use of loitering munitions and drones blunted the traditional advantages of mountainous defensive positions in Nagorno‑Karabakh; precision from the air outran assumptions drawn from the map.

Cyber operations add a further layer of volatility: attacks on financial systems, logistics hubs and power grids can be launched across borders without a single soldier crossing, as the 2007 cyberattack on Estonia and NotPetya (a destructive malware attack in 2017) made plain. To borrow Colin S. Gray’s framing, geography furnishes the stage; it does not write the script. Asymmetric instruments – lawfare, guerrilla tactics, economic coercion, information operations – allow the “weak” to frustrate or even defeat the “strong,” a dynamic classical geopolitics often missed when it reduced small states to pawns.

History offers ample “upsets”: Vietnam’s endurance against the United States (1955 – 1975); Finland’s initial resistance to the USSR in the early months of the Second World War; the Baltic states leveraging EU and NATO membership to protect themselves despite their size. Fatalism about location is not only analytically wrong; it tempts aggressors to underrate the resolve, ingenuity and coalition‑building capacity of those they deem geographically doomed.

Second: the normative trap. Invoking “natural” buffers and “historic” spheres of influence is a solvent of sovereignty and a ready pretext for coercion. What masquerades as description quickly turns prescriptive: because a great power borders a smaller neighbor, it claims an “entitlement” to dominate it. That logic collides with the post‑1945 guardrails – territorial integrity, the inadmissibility of conquest and the right of self‑determination, regardless of a state’s size. These guardrails are not moral niceties; they are stability mechanisms for an interdependent world.

Europe’s experience is instructive. Durable peace did not flow from reviving Yalta‑style partitions, but from legal equality among states and dense institutional integration. Spheres that must be sustained by coercion are brittle and invite backlash: the Soviet bloc unraveled once Moscow’s grip loosened. In our time, Russia’s attempt to re‑impose a sphere has produced the opposite of acquiescence – Finland and Sweden raced into NATO; Ukraine doubled down on anchoring itself in the West; even partners like Kazakhstan assert wider room for maneuver.

The broader lesson is straightforward: sphere‑thinking is anachronistic and strategically self‑defeating. It discounts the agency of medium and small powers, misprices reputational costs and misreads a world in which legitimacy is a currency of influence.

Third: the allure of autarky. Classical geopolitics prized self‑sufficiency. Haushofer’s pan‑regions aimed for it. In a networked economy, however, autarky is a costly mirage. Resilience does not mean cloning entire ecosystems at home; it means diversification and redundancy with trusted partners. “Fortress economies” forfeit economies of scale, global talent pools and collaborative R&D – and they ossify behind protective walls. The bill is exorbitant (replicating a full advanced‑technology stack domestically runs into the trillions), and the result is often inferior and late. Worse, autarky is brittle: when a home‑grown system fails, there is no external slack to draw upon.

A better test for “secure supply” is straightforward: Does the measure reduce systemic risk at reasonable cost and within a realistic timeframe? Blanket re‑shoring usually fails that test; targeted ally‑shoring (moving critical links to trusted partners) of genuinely vital inputs, paired with diversified sourcing for everything else, fares much better.

The pandemic underscored the case for surge capacity and buffers in specific chains (e.g., medical supplies) without implying that every country should build its own cutting‑edge fabrication plant. From Japan to Australia, joint investment in critical minerals and processing shows how to de‑risk dependence without sacrificing openness. Resilience emerges from interdependence with safeguards – not from isolation.

Fourth: neglect of soft and regulatory power. Classical models underweight legitimacy, norms and rule‑setting as multipliers of material power. In a networked world, reputational and regulatory credibility attract capital, firms and talent, with partners gravitating to jurisdictions that enforce clear, fair rules. Regulatory power travels farthest when it rests on market size, technological depth and coalition alignment; its reach is sector‑specific and conditional.

The “Brussels Effect” – the extraterritorial pull of EU rules – remains potent, but chiefly in consumer‑facing domains such as data protection (GDPR), sustainability reporting and product safety. In technology‑heavy or security‑salient sectors, diffusion increasingly requires transatlantic or minilateral alignment and leverage along supply chains. Rule‑making in finance and tech matters only when paired with market‑access incentives and credible enforcement; otherwise, normative diffusion remains aspirational. Capturing an industry standard (5G architectures, payment messaging, AI safety protocols) can yield durable leverage – but only where market share and coalition coverage sustain the economics of compliance.

Europe’s weight – and its exposure to coercion over energy, raw materials and markets – argues for treating regulatory reach as a multiplier, not a substitute, for industrial and hard power. Narrative authority matters as well: the ability to frame issues persuasively shapes diplomatic alignments and market leverage. After Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, more than a thousand companies, driven by reputational risk and normative stance, curtailed operations in Russia beyond what sanctions strictly required. Effects varied by sector and jurisdiction, yet the voluntary exit imposed real economic costs independent of state coercion. Power now has a significant ideological component that lines on a map and resource endowments alone cannot capture.

States seen as reliable rule‑abiders with transparent institutions find it easier to assemble coalitions, mobilize private finance and sustain frontier technology ecosystems. Those that flout rules court isolation. Regulatory and soft power, properly used, do not replace deterrence – they compound it.

These three case studies, and the pitfalls related to the Haushoferian vision of maps as absolutes, prove that geopolitics fit for the twenty‑first century must pair spatial insight with an appreciation of networks, norms and intangible assets. It should recognize that agency can rewrite scripts that maps seem to dictate, that state sovereignty cannot be taken away without inviting instability, that resilience is built through diversified interdependence rather than autarkic illusions, and that regulatory credibility and soft power multiply the effects of material capabilities. Anything less risks strategic myopia dressed up as cartographic certainty.

Chapter 6. How to Secure the Commons: Eight Rules for a Networked Order

If geography frames incentives while networks and norms shape outcomes, priorities should shift from carving spheres to securing the commons. That means layered, polycentric governance and enforceable minilateral coalitions, not vague universalism. The true “high ground” is the integrity of the systems on which all nations rely – and the capabilities to defend them, repair them fast and credibly retaliate for attacks. What follows are eight rules that make resilience measurable rather than aspirational: with clear metrics; they turn resilience from aspiration into a measurable program.

Rule 1 – Make protection of the commons a standing mission. Treat sea lanes, air corridors, orbital paths, undersea cables, and core cyber backbones as one system to be defended and repaired continuously, not only after a crisis. That means steady investment in the unglamorous enablers of the commons: mine countermeasures and de‑mining; maritime domain‑awareness networks that track piracy, drones and submarines in real time; ice‑capable ships and polar infrastructure for safe Arctic transit and search‑and‑rescue; resilient satellite constellations with rapid‑reconstitution plans; and cable monitoring with the ability to dispatch a repair vessel at short notice. We also need shared forensic attribution and incident‑response capacity, common cyber‑threat intelligence and zero‑trust network designs – embedded in minilateral corridor agreements and in “cable clubs” (operator consortia that co‑own undersea cables) with pooled insurance and pre‑funded repair contracts. Finally, bring insurers, classification societies, cable consortia, and major cloud providers into joint exercises, attribution drills and cost‑sharing arrangements so roles get rehearsed and recovery is fast.

Rule 2 – Operationalize legal deterrence with attribution playbooks. Alongside hardening physical assets, legal deterrence must be strengthened and anchored in coalitions that can enforce it. Allies already warn that deliberate attacks on undersea cables and other critical subsea infrastructure may trigger a joint response; those words should become practice through agreed attribution procedures and a graduated sanctions ladder, with cross‑domain options where appropriate. International law should clearly condemn and penalize malicious cyber operations and debris‑creating anti‑satellite tests, and set explicit rules for close‑approach space maneuvers and for debris mitigation – backed by verification and penalties. The aim is to put connectivity protection in the first tier of national security, guided by measurable targets – how quickly responsibility is assigned, how quickly systems are fixed (Mean Time to Repair, MTTR), and how quickly partners mobilize (Coalition Activation Time, CAT) – so that investments and exercises are disciplined by outcomes. A handful of missiles can sink a carrier, but a robust allied network that protects cables and timing signals (e.g., GPS time) and hardens data integrity – via encryption, traffic shaping, and zero‑trust architectures (“never trust, always verify”) – can deny adversaries the ability to disrupt global systems short of total war.

Rule 3 – Pursue interdependence without overdependence. On the economic front, security should follow a simple rule: stay connected, avoid single‑point failures. Autarky is a costly mirage; complacency about concentrated dependencies is equally dangerous. The practical alternative is targeted de‑risking: identify the few sectors where reliance on a strategic rival creates unacceptable leverage – Europe’s dependence on China for rare earths, or the West’s reliance on Taiwan for leading‑edge chips – and then onshore or ally‑shore what can be moved, while adding redundancy and buffers where relocation is unrealistic. For most other goods, supplier diversification and caps on concentration suffice. If one country supplies 60 percent of a given input, rebalance toward roughly 30 percent by shifting orders to other partners. That is not decoupling; it is risk‑aware rebalancing with clear supplier‑of‑last‑resort arrangements. Complement this with strategic stockpiles and switching capacity for truly critical goods – six‑month reserves of essential medicines, pre‑negotiated contingency contracts with allies, modular production lines that can be repurposed in emergencies – plus periodic supply‑chain stress tests and transparency requirements that surface hidden single points of failure.

Rule 4 – Keep export controls narrow, aligned, and enforceable. Export controls should focus on the small set of technologies that confer genuine military‑strategic edge – and be backed by credible enforcement and joint compliance monitoring. Controls work best when key suppliers act in concert and share circumvention intelligence, and when they are paired with positive measures – targeted subsidies, joint R&D, and workforce development – that keep partners onside. Recent trilateral steps by the United States, Japan and the Netherlands to restrict exports of extreme‑ultraviolet (EUV) lithography tools to China show how a unified front can close loopholes, while the US CHIPS Act and the EU Chips Act build allied capacity to offer alternatives to Chinese chip‑dominance.

Rule 5 – Compete in connectivity with bankable projects, not slogans. Connectivity is now a competitive domain; we must compete while upholding open norms. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative shows how ports, rail, power, and digital systems translate into influence and standards. Western efforts – from the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment onward – will matter only if they deliver bankable projects: well‑prepared proposals with credible environmental and social safeguards and transparent procurement. Too often, promising ideas stall before they reach a lender, nudging governments toward quicker, opaque alternatives. The fix lies upstream: fund project preparation and impact assessments, run open tenders, and scale independent quality‑certification schemes (e.g., the Blue Dot Network) to crowd in private capital. The aim is simple: make the open network the lower‑risk, higher‑value choice.

Rule 6 – Treat the “global middle” as co‑architects. Do not force binary alignment. Treat countries that are neither US allies nor Chinese clients – the “global middle” from India and Brazil to the Gulf, ASEAN, and key African partners – as co‑architects of an infrastructural commons. Offer modular cooperation aligned with local priorities (maritime domain awareness with India; sustainable agriculture and Amazon protection with Brazil; smart‑city infrastructure and public health with Southeast Asia) without demanding across‑the‑board alignment. Price alignment where it matters most – security and high tech – by protecting sensitive technologies and upholding freedom of navigation; tolerate autonomy where core interests are not at stake. The operative mantra: expand the overlap of interests, incentives and co‑owned projects by investing in what publics value (jobs, skills, disaster relief, climate adaptation) and by sharing ownership through co‑financing and co‑design rather than take‑it‑or‑leave‑it packages. Influence follows tangible benefits and respect, not demands for fealty.

Rule 7 – Build guardrails for crowded domains. As competition deepens, it needs guardrails. Crowded arenas – the South China Sea, Earth’s orbit, and cyberspace – are prone to accidents and miscalculation. A close naval encounter, a satellite collision, or a misattributed cyberattack can escalate if channels are cold. Risk reduction is not a nicety; it is a necessity. Hotlines must exist, be tested and be used. At sea, reduce friction through predictable signaling around major exercises, mutually observed protocols (e.g., refraining from illuminating foreign ships with fire‑control radar), and updated equivalents of the US – Soviet Incidents at Sea Agreement to prevent dangerous encounters. In space and cyber, agree upon norms for orbital traffic management, debris mitigation and mutual restraint regarding GPS and communications satellites, alongside shared attribution frameworks and auditability. Because attribution can be contested or spoofed, coalitions should set confidence thresholds and require independent technical review before sanctions ladders trigger. These are pragmatic steps to keep sparks from becoming a forest fire.

Rule 8 – Enforce rules when breached. Violations of sovereignty, freedom of navigation, non‑aggression, or treaty commitments should trigger pre‑committed, coalition‑based consequences – not as moral posturing, but to deter copycats. If borders can be redrawn without penalty, the independence of every state becomes uncertain. The toolbox is graded: sanctions, diplomatic isolation, legal judgments, and – when necessary – credible military posture and proportionate retaliation. Together, they raise the price of coercion and reduce the odds of recurrence. Think of it as policing the global neighborhood: fail to prosecute one burglary, and you invite the next. The aim is not to revive the fatalism of classical geopolitics, but to harness its core realist insight – that power matters – in service of rules backed by power. By making rule‑breaking unprofitable, we can sustain a stable order even amid sharper competition.

Chapter 7. The Stage, the Script, the Ending

Haushofer’s ghost is worth keeping in view – to mark both what it clarifies and where it misleads. Geography still frames incentives; but in a world routed through cables, satellites, standards and finance, outcomes are decided where flows, attribution and enforcement intersect. Control over networks can rival – and at times surpass – control over territory, provided responsibility can be credibly assigned, legal levers exist, and coalitions are willing to impose costs.

What follows is less a recap than a test for strategy. Success in “securing the commons” will not mean fewer shocks; it will mean systems that fail safely and recover fast. The practical yardsticks are already visible in this essay’s rules: time‑to‑attribute, mean time to repair and coalition activation time. If these metrics decline across sea lanes, orbits, air corridors and data backbones, deterrence by denial and punishment is finally moving from aspiration to operating system.

Three political problems decide whether that operating system endures. Allocation: Who pays for redundancy, rapid repair and insurance backstops in a space where private actors (cloud providers, cable consortia, insurers, classification societies) carry much of the risk? Durable governance must formalize their role – through exercises, attribution drills and pre‑funded repair contracts – rather than treating them as afterthoughts. Inclusion: an open commons cannot be run as a closed club. Treat the global middle as co‑architects, not clients, by co‑financing and co‑designing modular projects where interests overlap – even when full alignment is neither possible nor necessary. Restraint: crowded domains need guardrails that are used, audited and verified. Misattribution is a structural hazard; confidence thresholds and independent technical review before sanction ladders trigger are therefore not niceties but safety valves.

These criteria enable falsifiable predictions. If we get them right, we should observe declining insurance spreads on critical routes after incidents; quicker restoration of traffic following cable cuts or satellite outages; fewer single‑point dependencies in critical inputs; and coalitions that can act across domains without improvisation. If we get them wrong, we should expect the reverse: geopolitics devolves back into spheres not because maps regained magic, but because networks proved brittle, attribution stayed contested, and enforcement coalitions hesitated.

In that sense, the point of revisiting Haushofer is not to exhume a doctrine but to discipline statecraft. Keep the map as a lens, drop the myth. An order that protects shared connective tissue with measurable resilience, polycentric but enforceable rules, and coalitions prepared to act will remain open even as competition sharpens. That is a more demanding vision than fatalism or slogans – and the one least vulnerable to cartographic hubris.

Author’s note:

I wish to thank the reviewers and several colleagues for their insightful and constructive feedback on an earlier version of this article. My deepest gratitude goes to Oliver Jung, associate at GPPi, whose invaluable support and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this article into its current form. Any remaining errors or ambiguities are, of course, solely my responsibility.