Germany Needs to Rethink Competitiveness for a Hostile World

In February, Germany’s likely next chancellor Friedrich Merz made a promise that he would always be guided by a central question: “Does this government decision strengthen the competitiveness of our industry or harm it?” That sounds determined but suffers from a fatal flaw. Merz’ understanding of competitiveness is stuck in a world of the past. In that world, cost-cutting and deregulation offered plausible ways to sustain Germany as an export champion. But in today’s world, US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, are setting a very different tone in Germany’s two largest export markets beyond Europe.

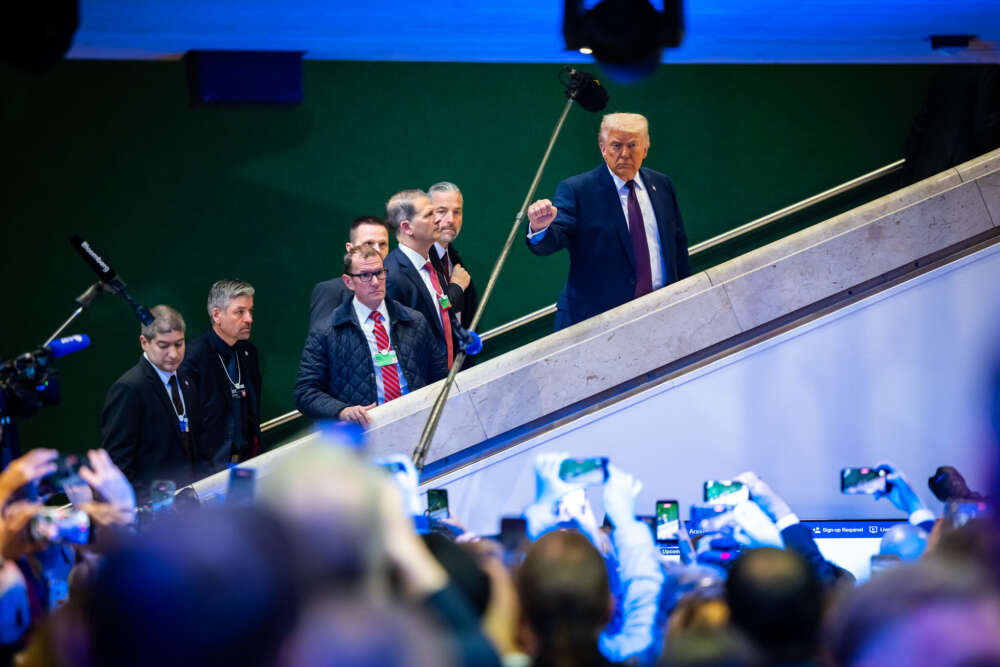

Trump’s misleadingly labeled “reciprocal tariffs” sent shockwaves through the global economy in early April. While it remains unclear whether they are truly intended to fundamentally restructure the global trading and financial order, to generate revenues for the US budget, or to serve as leverage to extract concessions in other policy areas, a sustained German trade surplus vis-à-vis the United States is clearly anathema to the US president. Moreover, he is seeking to neutralize the EU as a regulatory player that could pose a threat to the interests of US technology companies. Meanwhile, Xi is pushing policies to help Chinese companies achieve global dominance in Germany’s core industries such as automobiles, mechanical engineering, and chemicals — also in Europe. Both Trump and Xi are ruthlessly weaponizing dependencies.

Merz has already demonstrated his ability to leave outdated assumptions behind, waking up just days after the election to the need for a debt-fueled special fund for defense and infrastructure investment and for reforming the “debt brake” rules that had artificially constrained previous governments. He should now transform the idea of competitiveness to defend Germany’s social market economy in a hostile world. As Janka Oertel has pointed out in the discussion on China policy, the German language offers a nimble compound noun for this new lodestar: Systemwettbewerbsfähigkeit, or the capability of engaging in systemic competition. In the confrontation with Trump’s “America First” tech-oligarchic capitalism and Beijing’s authoritarian state capitalism, this new paradigm will enable Germany to resist economic coercion and unfair competition while reducing its excessive reliance on exports.

The Downfall of the Old Model

Many advocates of competitiveness have a one-sided view of the recent decades of success of German companies in global markets. Certainly, years of wage restraint and the labor market reforms in the early 2000s played a role in laying the groundwork for the golden age of German industry in the 2010s. However, in addition to the euro, which effectively created a significantly undervalued currency from a national point of view, a key factor was also a very favorable foreign policy environment. Thanks also to cheap energy from Russia, German companies could rely on good business in the US and China, two huge, fast-growing economies where German exports were welcome.

It is this second part of the story that has taken the more dramatic turn in recent years. Yes, rising wages, energy costs, and overregulation are increasingly affecting companies in Germany. Still, the country recorded a trade surplus of over €63 billion with the US in 2023 — the highest ever, belying the notion of a general crisis of competitiveness of German products. However, Trump sees this trade imbalance as a direct attack on US interests. He is now using tariffs to force production shifts to the US and is ruthlessly exploiting other countries’ dependencies for blackmail.

At the same time, Chinese firms, with massive state support, are launching a frontal assault on exactly the sectors where German companies have long been global leaders. China is not only systematically displacing German competitors in its own market, but also flooding the rest of the world with subsidized goods to permanently eliminate competitors in key sectors. Xi is explicit about his strategic goals. In 2020, he declared that China must become independent in all security-relevant areas while increasing the world’s dependence on Chinese supply chains.

Instead of decisively resisting this agenda, outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz, like his predecessor Angela Merkel before him, largely remained passive, driven by a dangerous mix of blind faith in the superiority of the German model and fear of Chinese retaliation against German companies. The most drastic example was Germany’s opposition to the European Union’s countervailing duties on Chinese electric cars in 2024, a disastrous move that Merz also supported at the time. While views in the German business community are far from uniform, the powerful auto executives appear to be prioritizing short-term sales figures in their declining Chinese market over the long-term survival of their companies. Moreover, the illusion that China is a “fitness center” where German companies can train for competition on global markets is still widespread. In reality, German firms are struggling on the treadmill while Beijing is pumping up their Chinese competitors with steroids in the form of political and financial support.

This short-sighted thinking is leaving Germany defenseless against a looming “China Shock 2.0,” where the survival of Germany’s key industries is at stake — especially as the effective closure of the US market for most products due to the escalating US tariffs means that Chinese overcapacities will be diverted even more toward the EU.

In this situation, it is dangerous to rely solely on supply-side reforms in a misguided bid to regain the title of “the world’s export champion,” or Exportweltmeister. Certainly, Germany needs to lower energy prices, slash regulations, and find solutions for the skilled labor shortages. Merz is right when he says that “Germany should create good framework conditions for all instead of high subsidies for a few.” However, a thoroughly reformed German state apparatus will have to play a crucial role to support key industries and especially high-tech innovation — as has historically always been the case, notably in the US.

Investing in System Competitiveness

There are still sizeable export markets to pursue outside the US and China, and the EU should negotiate to lower barriers to access wherever possible. That’s why it makes sense for the EU to quickly ratify the EU-Mercosur treaty and fast-track the conclusion of an EU-India trade and investment deal. But above all, Germany needs to reinvent its model to protect its prosperity and security in a time of systemic competition and hostile external forces.

First, Germany needs to pursue stronger measures, in concert with its European partners, to protect key sectors from unfair competition. European leaders need to agree on a list of critical industries that they absolutely want to keep on the continent, be it due to concerns about security threats or economic coercion or because their role in providing employment and innovation capacity outweighs the benefits of cheap imports from elsewhere. As Sander Tordoir convincingly argues, the fact that Europe’s heavy industry base is stronger than that of the US is a trump card in times of urgent rearmament needs. To this end, at both the national and EU levels, all available instruments need be used in a creative way, ranging from countervailing duties and “Made in EU” (or “by group of trusted allies”) clauses to regulation.

Security-relevant areas require special treatment, as exemplified by the United States with a new rule that effectively excludes Chinese suppliers from the American market for connected vehicles. Given the extent to which China and the US have already abandoned the fundamental rules of the multilateral trading system, many measures will probably even be WTO-compliant. Reliability on trade is an asset for Europe vis-à-vis smaller players in times of Trump. At the same time, Europe needs to be resolute and flexible. “Within WTO rules where possible — beyond them where necessary” must be the guiding principle.

Second, building on steps such as the “anti-coercion instrument,” the German government must help further develop the EU-level toolbox against economic coercion and support its decisive application in critical situations. Control over access to the still highly attractive European market remains the EU’s most important source of leverage, which should be used even more consciously in the future. At the same time, efforts to identify and reduce critical dependencies on both China and the US clearly need to be intensified.

Berlin must finally abandon the notion that earnest appeals to the business community and better corporate risk management will suffice, given the frequent divergences between public and private interest and major collective action problems in areas such as diversifying sources of raw materials. Since it is, even in a best-case scenario, not realistic for Europe to eliminate all dependencies on unreliable actors, these efforts need to be complemented by initiatives to establish its own “strategic indispensability” in the form of strengths in important technological niches that can be politically leveraged when necessary. This will also require advances in areas such as export and investment controls as well as research security.

Third, and most fundamentally, the next German government should drive a deliberate effort to make Germany less dependent on exports outside the EU by boosting domestic demand and strengthening the EU’s internal market. This includes eliminating remaining barriers within the EU, which still correspond to a tariff of 45 percent on goods and 110 percent on services. At the same time, overdue investments in defense and infrastructure modernization must be carried out in such a way that a large part of the resulting demand benefits European suppliers and production.

The Key Question

Finally, distributional issues must be recognized as central to building a more resilient economic model. The increasing concentration of wealth and income inequality not only creates political risk in its own right, but also hinders the necessary reduction of export dependency, given that lower-income groups have a significantly higher propensity to use additional income available for consumption.

Germany’s model has never faced as much pressure as it does today. Only by combining reforms, investments, and protective measures can the country continue the success story of the social market economy and sustain its economic and technological foundations also for military deterrence and defense. That is why ahead of every major decision as chancellor, Friedrich Merz should ask himself: “Does this strengthen our Systemwettbewerbsfähigkeit?”

This article was originally published by Internationale Politik Quarterly on April 16, 2025.