From Just in Time to Just in Case

An editorial in this week’s Global Times, the flagship newspaper of the Chinese party-state, argues that Beijing is not weaponizing Europe’s dependencies on China’s critical raw materials. Instead, it claims, the export controls — which have significant repercussions for European industrial production — are legally sound and reflect “China’s consistent goal of maintaining global peace and regional stability.” A nice propaganda lie. In reality, China is blatantly using Europe’s near-complete reliance on its many critical raw materials as leverage in negotiations. It is refreshing that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recently criticized “China’s coercion through export restrictions,” noting that Beijing is “using this quasi-monopoly not only as a bargaining chip, but also weaponizing it to undermine competitors in key industries.”

What is troubling is that some representatives of German industry still seem to trust Beijing’s propaganda. Maximilian Butek from the German Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, for example, said China had no intention of restricting European access to rare earths. In an earlier article in the Global Times, his colleague, Oliver Oehms in Beijing, called for the German government to focus more on China’s role as an innovation partner. In April, representatives from three dozen German companies published a paper urging a more conciliatory approach to Beijing. They published it anonymously out of fear of being branded as “naive China sympathizers.” But “naivety” is a rather generous term for positions that amount to willful denial of reality.

China has openly targeted Germany’s core industries with its “Made in China 2025” strategy — from automotive and chemicals to mechanical engineering. And it has systematically created dependencies for critical raw materials. For a long time, Germany welcomed this, both because China delivered materials cheaply, and because the processing of rare earths and metals is often highly polluting. China, in this sense, has been doing the dirty work for Germany.

However, since at least 2010, when Beijing imposed an embargo on rare earths against Japan following territorial disputes in the East China Sea, Germany has known that these dependencies pose a massive risk. Only in recent years has the German government made more serious efforts to reduce raw material dependencies, but its shift from a “just-in-time” efficiency mindset to a “just-in-case” resilience approach has been too half-hearted.

Without clear regulatory guidelines and incentives, German companies will continue to prioritize price when choosing suppliers — and that often means choosing China, as alternative sources tend to be significantly more expensive. But raw material markets are political. It is therefore imperative that the state not only sets clear requirements for responsible sourcing but also actively partners with companies to navigate and shape these markets.

Germany’s raw materials fund, established last year, needs significantly more financial resources to support investments in alternative sources of critical raw materials, ideally backed by long-term offtake guarantees that provide security for both suppliers and investors. This effort should be complemented by the development of strategic stockpiles, better recycling systems, and more investment in innovative processes that reduce the need for critical materials. All this must happen in close coordination with other European and international partners. Germany can learn a lot from Japan in this regard.

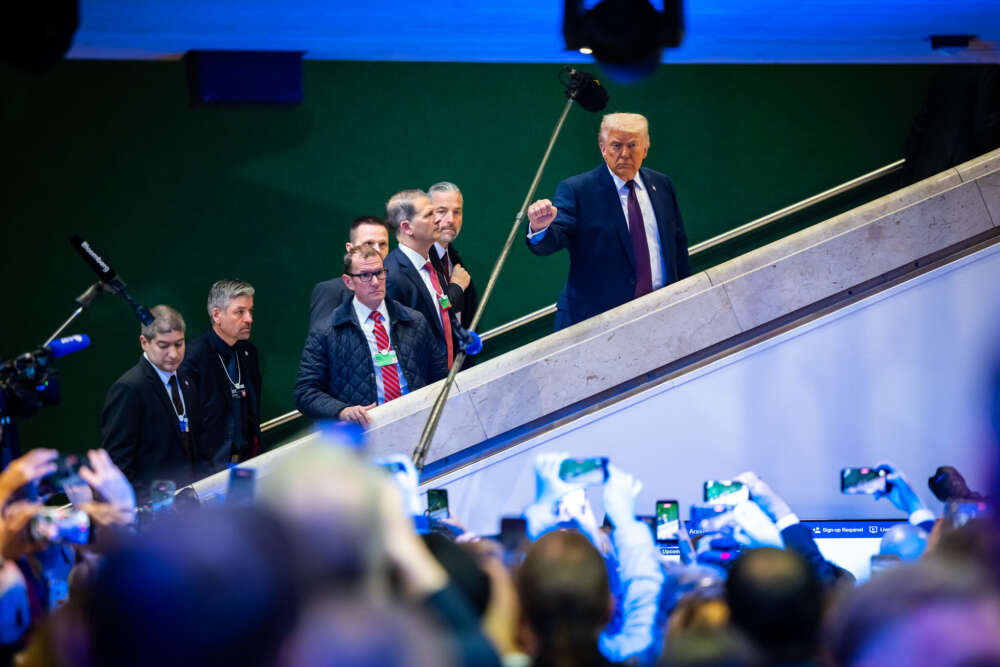

Fortunately, the BDI (Federation of German Industries), unlike the DIHK (Association of German Chambers of Commerce and Industry), advocates reducing dependencies on China and investing in Germany’s core strengths. As early as 2019, the BDI had already identified China as a “systemic competitor.” Today, BDI President Peter Leibinger not only promotes investment in “vertical supply chains in particularly critical areas” as a defensive move to reduce dependencies, but also calls for an offensive strategy modeled on Japan’s approach of “strategic indispensability”: “the targeted development of strengths that give [Germany] bargaining power.” Leibinger rightly emphasizes the need for better collaboration between politics, business and science, arguing that through this collaboration, German companies can identify technologies that only they master, and then expand on them. The new National Security Council should play a central role here. Positioned at the intersection of security, economy, and technology, this council should focus on safeguarding and evolving Germany’s endangered open social market economy model in an increasingly hostile world shaped by Xis, Trumps, and Putins.

This commentary was originally published in German by Handelsblatt on July 3, 2025.