Pitfalls Between Science, Politics and Public Debate: Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic

In early July 2021, Armin Laschet, the German conservative party’s candidate to succeed Angela Merkel as chancellor of Germany, found himself in a political firestorm. During a parliamentary debate on the role of a council of experts on the COVID-19 pandemic that had advised Laschet in his role as prime minister of North-Rhine Westphalia, he had stated: “I rarely if ever agree with the AfD. But today you said a sentence that is true. If somebody comes and says ‘science’ says this and that, one is well advised to question what the agenda behind this is. Because science always has minority opinions.” Laschet warned of reducing scientific discussions to “instrumentalization for political purposes” – and was heavily criticized for this statement. However, his critics did not just focus on Laschet’s ill-advised support for a speaker of the far-right AfD party. They also accused him of an anti-scientific attitude, and of legitimizing questionable minority opinions.

Given the magnitude of both the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic and the climate crisis, the extent and manner in which politicians rely on science to inform policymaking has become an ever more central – and contested – issue. The pandemic in particular has exposed many typical pitfalls that lurk in the triangular relationship between science, politics and public debate. Scientists, policymakers and the media can and should learn lessons from this on how policymakers and the public can best draw on scientific expertise. And in doing so, it is worth taking a closer look at one particular case, namely that of an informal group of scientists (consisting of economists, sociologists and China researchers) that was formed by State Secretary Markus Kerber at the German Ministry of the Interior (BMI). Within four days, from March 19 to 22, 2020, this group wrote a paper entitled “How We Get COVID-19 Under Control” – a paper with a fascinating and highly peculiar genesis and reception.

In the paper, the experts outline three scenarios for the spread of the novel coronavirus, including the expected death toll: the “worst case” (with an estimated one million deaths in Germany in 2020), the “stretch” scenario (220,000 deaths), and “hammer and dance” (12,000 deaths). The advisors also propose a large number of political recommendations for action to avoid the worst case scenario. Among other ideas, they call for subordinating data protection in favor of health protection concerns and argued that “the use of big data and location tracking is inevitable.” Much of the paper addresses how to successfully secure public consent for restrictive measures.

As the introduction points out, the key to getting the public onboard is to emphasize the worst case scenario: “To mobilize society’s capacity for endurance, concealing the worst case scenario is not an option.” Accordingly, the paper goes into great detail about how to “shock” the public into consenting to temporary restrictions on their freedom:

“To achieve the desired shock effect, the concrete effects of the contagion on human society must be made clear: 1) Many seriously ill people are brought to the hospital by their relatives, but are turned away and die agonizingly at home, gasping for air. Suffocation, or not getting enough air, is a primal fear for every human being. As is the situation in which nothing can be done to help families whose lives are in danger. The pictures from Italy are disturbing. 2) ‘Children will hardly suffer from the epidemic’: False. Children will easily become infected even with curfew restrictions in place, e.g., from the neighbor’s children. If they then infect their parents and one of them dies at home in agony, and the children feel that they are to blame because, for example, they forgot to wash their hands after playing, this is the worst thing a child could ever experience.”

The text was initially classified, but as early as the end of March, the Süddeutsche Zeitung reported using information from a “confidential strategy paper.” The website FragDenStaat eventually published the paper on April 1, 2020, after which Germany’s Interior Ministry also posted the full text online.

After its publication, opposition parties in the Bundestag asked a lot of questions about the origins of the paper. In its answers, the Interior Ministry described its own role as “purely coordinating and editorial (preparation of a summary)” and claimed that “the development of the paper arose from a professional dialogue between the BMI and various social scientists, and was initiated by the scientists.”

More than a year later, the expert paper is still making waves. At the beginning of February 2021, Welt am Sonntag published its findings on the genesis of the document, which were based on insights gained from e‑mail correspondences between the researchers and BMI State Secretary Markus Kerber. These messages were obtained by a Berlin lawyer by way of a freedom of information request. Journalists Anette Dowideit and Alexander Nabert write:

“During those four days, Kerber and other high-ranking ministry officials meticulously followed the researchers’ work and dictated a clear course of action. Records shows that there were telephone conferences between the BMI and the researchers at short intervals while they worked on their model and the resulting recommendations.”

And they conclude: “Almost 200 pages of e‑mails prove that the researchers, at least in this case, acted by no means as independently as scientists and the German government have consistently claimed since the beginning of the pandemic – but instead worked toward a fixed result predetermined by politicians.” In doing so, science becomes “the extended arm of politics.” In response, Dietmar Bartsch, parliamentary group leader of Germany’s left party, criticized: “When science gives up its independence, credibility suffers. But trust and credibility are key to strengthening acceptance for measures in a crisis.”

At the end of February, Welt am Sonntag published another article dealing with Otto Kölbl, a member of the Interior Ministry’s ad hoc task force. He authored the passages on “shock effect” in the draft paper, leading to the special interest in his background. Kölbl, a 52-year-old German scholar, is both a language examiner for German and a doctoral student in German studies at the University of Lausanne. The institution stopped Kölbl from using the university’s official e‑mail address for his publications related to the COVID-19 pandemic. When State Secretary Kerber sent an e‑mail to the responsible dean at the University of Lausanne in support of Kölbl’s role as an advisor to the Interior Ministry, the university initially found the message “not plausible,” as they could not believe a senior German government official would take an interest in Kölbl’s opinions on the pandemic. They emphasized that Kölbl’s activities related to COVID-19 had “no connection whatsoever” to his work as a language examiner for the university.

On his Twitter profile, Kölbl continues to tout himself as a member of the currently inactive BMI Coronavirus task force. He is, as made clear by his public statements, a Mao fan as well as an ardent defender of the Chinese party-state and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPC) repression tactics. For Andreas Rosenfelder, WELT’s head of feature pages, the report on Kölbl “puts the German government’s course concerning pandemic policy in a new light and is required reading for anyone who wonders how the authoritarian element found its way into a liberal society.”

The accusations put forward in the two Welt articles cannot both be true at the same time. Either CPC fan and paper co-author Otto Kölbl convinced Germany’s Interior Ministry to adopt repressive measures during the pandemic that are inspired by China’s policies – or the researchers delivered a commissioned work according to the ministry’s political guidelines.

On closer examination, the idea that Kölbl influenced the German government’s direction toward “authoritarian elements” can quickly be dismissed. The preferences of State Secretary Kerber and Interior Minister Horst Seehofer were clear early on in the pandemic. Seehofer in particular pushed for tough measures as early as February 2000, as journalist Robin Alexander details in his book Machtverfall. Both State Secretary Kerber and Interior Minister Seehofer have survived threatening – even life-threatening – viral illnesses in recent years. This fact may have contributed to their early preference for decisive pandemic containment, reported outlets like ZEIT. As a comparison, in the early weeks of the pandemic, German Chancellor Angela Merkel still accepted that everyone would eventually be infected with COVID-19, and that the task was to simply slow the wave so that hospitals would not be overwhelmed.

As Alexander further details in his book (p. 215), it was Seehofer who directed Kerber to seek out scientific support in favor of drawing a tougher line on COVID-19 restrictions. A four-hour meeting on March 11, 2020 with virologists Lothar Wieler and Christian Drosten – at the time the most important scientific advisors of Chancellor Merkel and Health Minister Jens Spahn – had left Seehofer deeply dissatisfied. As Alexander writes, Seehofer “decided to no longer rely on the virologists advising Merkel and Spahn.” To this end, Kerber sought out support and additional ideas for tough policy from the German academic community. During this process, he became aware of Kölbl through a paper on lessons from China’s Coronavirus response in Wuhan that he wrote together with Bonn-based China researcher Maximilian Mayer – one of the current heads of the #NoCovid movement. Kölbl and Mayer argued that “there is no alternative to containment of COVID-19.”

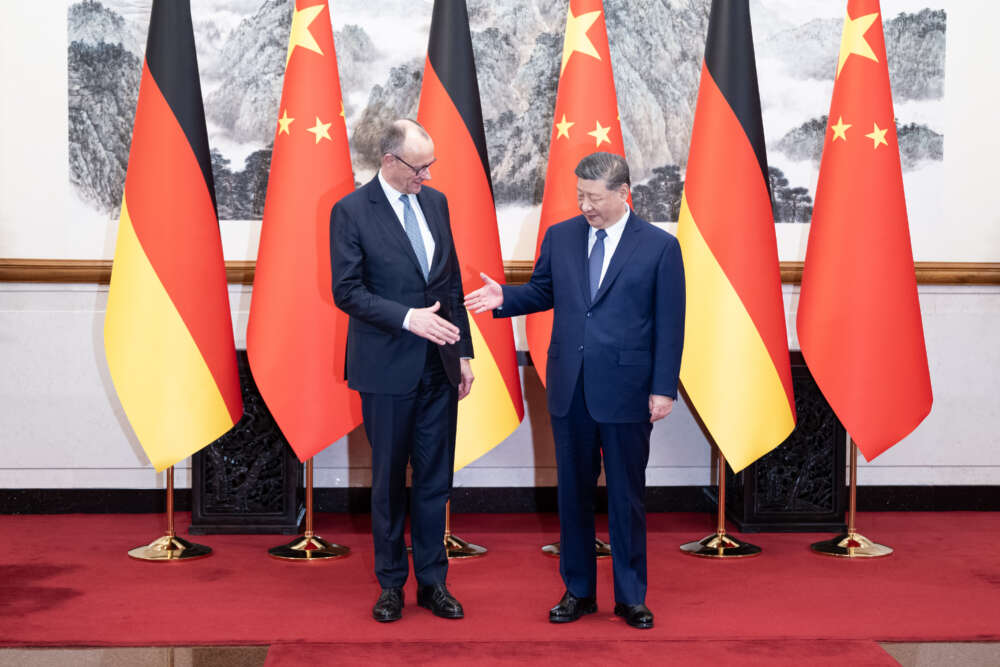

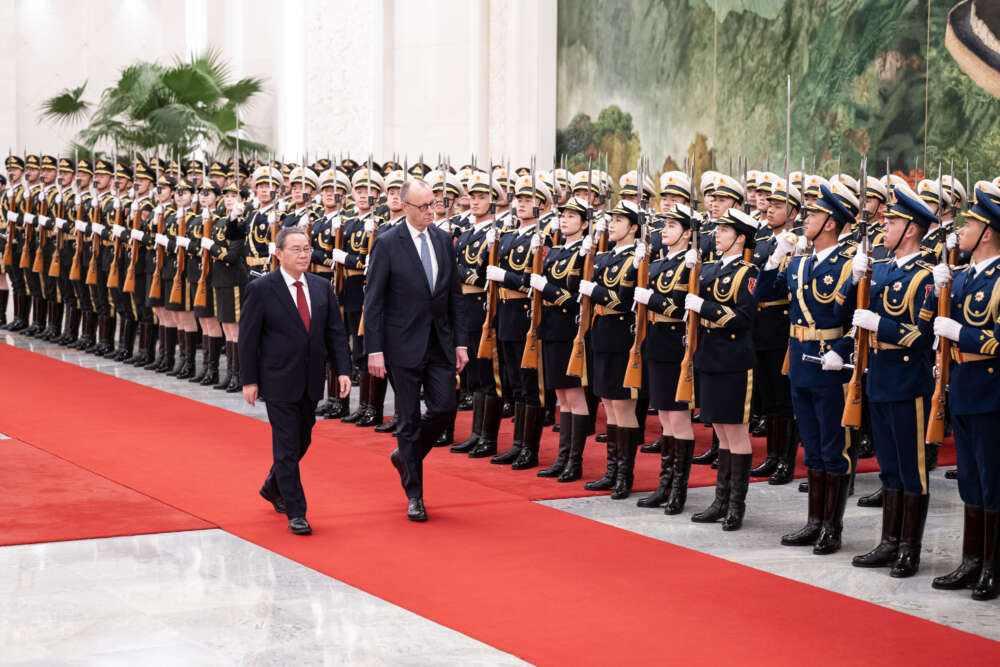

Undoubtedly, Kerber made a political mistake by not checking Kölbl’s background further before appointing him to the BMI expert panel – especially after the University of Lausanne so clearly distanced itself from the association. A person with such abhorrent political views on the CPC should not be appointed to a public German task force. However, it would be wrong to assume that Kerber in any way sympathizes with Kölbl’s views on the CPC. The state secretary stands out among Germany’s top officials as somebody who is extremely critical of the role and influence of the Chinese party-state and who advocates for Germany to adopt a robust China policy. For this reason, it would be absurd to assume that Kerber shares any of Kölbl’s views on China. It is much more likely that Kölbl’s positions on the CPC were unknown to the BMI at the time of his appointment to the task force.

What about the second accusation that scientists let themselves be controlled by Kerber and his ministry – in other words, that the researchers provided arguments for a “politically determined result” and thus undermined their scientific independence? Certainly, Kerber only appointed experts (notably, there were no female researchers in the group) whose positions he tended to share. Without question, Kerber wanted to gather arguments and proposals in favor of tough restrictions, and hoped to use the scientists’ paper to convince the rest of the German government of the same. That is hardly surprising – policymakers often choose their advisers based on whether the latter fundamentally agrees with their own beliefs. And they use the findings to further their position in the political debate within the government or in public.

Scientific advisors are not necessarily compromised by their awareness that their advice is sought to enable or legitimize political action. They can still use their advisory work to suggest proposals that they believe will bring about political and social improvements, or simply help better inform decision-makers. However, it is crucial to keep one basic fact in mind: in most cases, these experts are asked to provide specific recommendations for political action. These suggestions may be based on scientific research and expertise, but in most cases, they go well beyond that. Not all political recommendations for action can, for example, be scientifically substantiated in terms of their effectiveness. And even where the advice is backed by science evidence, there always remains a normative element that surrounds political action – whether that is about what the goal should be or what trade-offs we should make vis-à-vis other priorities.

Of course, this is not a new phenomenon – think, for example, of natural scientists who vehemently oppose nuclear weapons. A nuclear physicist who advocates for Germany to sign the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons does not do so solely based on their scientific expertise. Normative beliefs and values play a central role.

Further, many of the questions that researchers are asked by politicians and journalists are aimed at answers containing normative valuations – and therefore go far beyond objective facts and established research findings. The “shock effect” central to the recent BMI paper written is just one example.

In heated political and social debates, the researchers who make public recommendations or act as advisors to decision-makers will inevitably be caught in the crossfire of criticism. Often, these advisers become themselves political targets, which can put them in an uncomfortable position. However, it would be a serious loss for the quality of public debates and political decision-making if researchers were deterred by this pressure and instead retreated to the ivory tower.

There are some important lessons to be learned from the controversy surrounding the BMI’s Corona Advisory Group – specifically, about how scientists, policymakers and journalists can strike the difficult balance between science, politics and the public to benefit all sides.

First, attempting to disqualify others through ad hominem attacks is not a useful tactic. Two DER SPIEGEL editors did so rabidly in an interview with Berlin virologist Christian Drosten, in which they argued, “in the past year, more damage has probably been done by experts who repeatedly argued against scientifically based measures – for example, Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit and Hendrik Streeck – than by corona deniers.” Such an outlandish accusation camouflaged as a question should not have any place in quality journalism.

The fact that the leadership of DER SPIEGEL publicly defended the two editors’ comments undermines the credibility of science journalism. Equally counterproductive, however, was the public attack by virologist Schmidt-Chanasit against his fellow scientist Maximilian Mayer, in which he ideologically placed Mayer next to his Mao-worshipping co-author Kölbl in order to question the credibility of the #NoCovid approach.

It also did not help that Christian Drosten, one of the most influential experts in the COVID-19 pandemic, referred to a statement co-signed by Schmidt-Chanasit and Bonn-based virologist Hendrik Streeck an example of “pseudo-expertise.” Drosten also claimed that the phrase “learning to live with the virus” – a term often used by Streeck – falls in the realm of “science denial.”

Second: All pandemic-related actors – in science, politics and the public – should establish maximum possible transparency. There are good reasons not to publish all of the details when scientists advise politicians, including for confidentiality. However, such valid reasons hardly existed in the case of the BMI’s Coronavirus task force: it is unlikely that the researchers handled secret government information. And when the internal report from a group of experts advising politicians is first classified as “confidential”, but a short time later made available to individual journalists to selectively report on, it undermines the credibility of all those involved – and is also serves as grist to the mill of conspiracy theorists.

To avoid this situation, the BMI should have proactively published the report on its website. It also did not help that the BMI downplayed its role in the genesis of the paper in its response to parliamentary inquiries – the e‑mail correspondence between those involved, which has since been made public, suggests that the ministry took a very active role in shaping the work of the task force.

Third, roles should be clearly distributed. Scientists give recommendations, but politicians decide on the course of action – and should not hide behind science when making uncomfortable decisions. For example, it was extremely counterproductive for Berlin Mayor Michael Müller to argue, as justification for extending contact restrictions in January 2021, that “without exception” all of the experts consulted had confirmed that the restrictions were the right choice. The fact is: there is no unanimous position in the scientific community on this political decision. Instead of validating his decision, Müller’s statement rather reveals the selective choice of his interlocutors from the scientific community.

When politicians suggest the uniformity of scientific opinion to legitimize uncomfortable decisions, the credibility of both science and politics suffer. As sociologist Alexander Bogner put it in his book, The Epistemization of the Political: “a policy that sees itself – thanks to its agreement with science – as without alternatives provokes a policy of alternative facts.” (page 121)

This formulation is somewhat exaggerated. But relying on the claim that “there is no alternative” supposedly based on science may well help to fuel anti-scientific protest movements. Swiss historian Caspar Hirschi underscores this danger in an essay: “Populists use expertocratic distortion to paint a doomed picture of expert rule, expertocrats use the populist one to shield expert testimony from democratic discussion.” As an antidote, Hirschi offers the sound advice that “democracy is strongest when political decisions are based as much as possible on scientific expertise, and legitimized with it as little as possible.”

Fourth, scientists should refrain from claiming scientific absolutes when making policy recommendations. For example, virologist and #NoCovid advocate Melanie Brinkmann often presents her beliefs as scientifically uncontroversial and classifies scientists with other opinions as an irrelevant minority. In addition, experts who stressed the strong seasonal effects on the spread of the Coronavirus were long regarded as holding a fringe position, only to be proven right by recent studies. Denying the plurality of the spectrum of scientific opinion can further undermine trust in science. That seems to have been the point Laschet also wanted to make with his somewhat ill-fated intervention in early July.

Sociologist Bogner aptly warns against the illusion of “purely knowledge driven politics.” Such a notion, he claims, is “based on the mistaken assumption that there are always ‘right’ or true answers to political disputes.” But, as Bogner goes on to write, that is not the case: “Even if we have reliable figures on the infectiousness of a virus or on the extent of global warming, those numbers contain no blueprint for political action.”

Especially in times of crisis, scientific evidence can provide an important impetus for political debates about the “right” course forward. As shown in the current debates on the Coronavirus pandemic, such societal discussions function best when they are conducted with transparency, openness to different positions and a clear division of roles between politics and science.

Incidentally, this is also the best way to defend academic freedom and harness its power for debates in an open society.

This commentary was originally published in German by Cicero Magazin on May 05, 2021. The English version is a part of our web magazine COVID-19 and Academic Freedom.