German Greens’ Reality Check

Why a Green Government Will Frustrate the Country’s Allies on Security

The German Greens are riding high. The party surged to a lead in at least one recent opinion poll after unveiling their first-ever candidate for chancellor, 40-year-old Annalena Baerbock. A lot can still happen between now and Germany’s September 26 elections, but it’s becoming hard to imagine a scenario in which the next coalition government doesn’t include the Greens.

International commentators have gotten their hopes high for what this means for German foreign and security policy. A recent feature in the New York Times celebrated the Greens as a “pragmatic party promising an assertive stance abroad,” committed to “Germany’s membership in NATO and its strong alliance with the United States.” Another analyst argues that a coalition of Greens and the conservative Christian Democrats “could finally create a coherent defense policy.”

Those commentators are likely to be disappointed. A government in which the Greens play a key role is unlikely to give Germany the security policy its NATO allies expect. To be sure, Baerbock leads a party that’s moved away from its anti-NATO, pacifist roots in the peace movement 40 years ago. They now see the military alliance as an “indispensable actor for European security” and have strong commitment to strengthening multilateralism and the European Union.

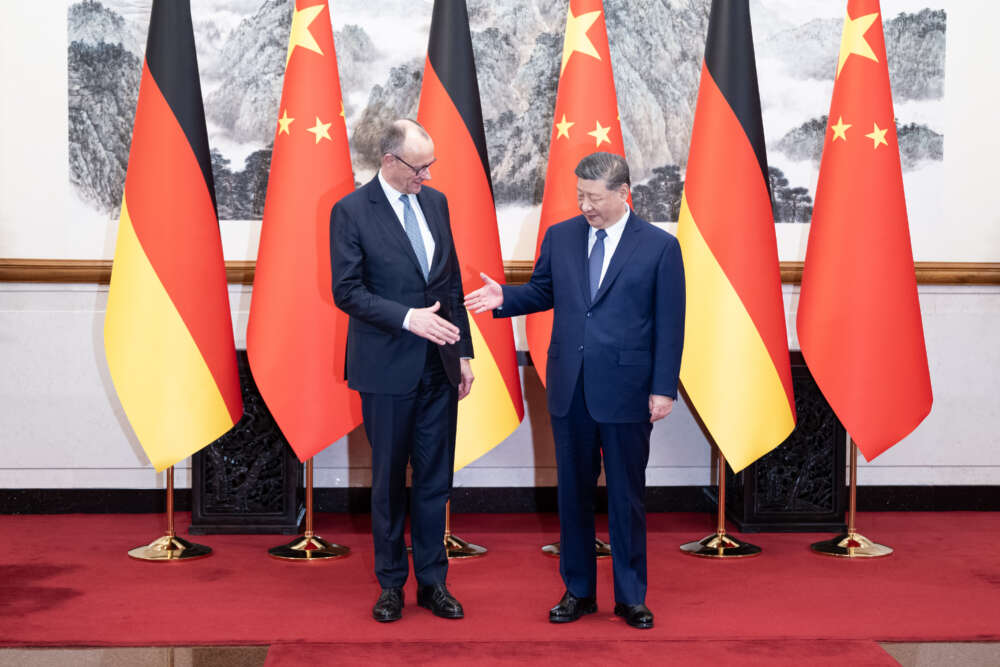

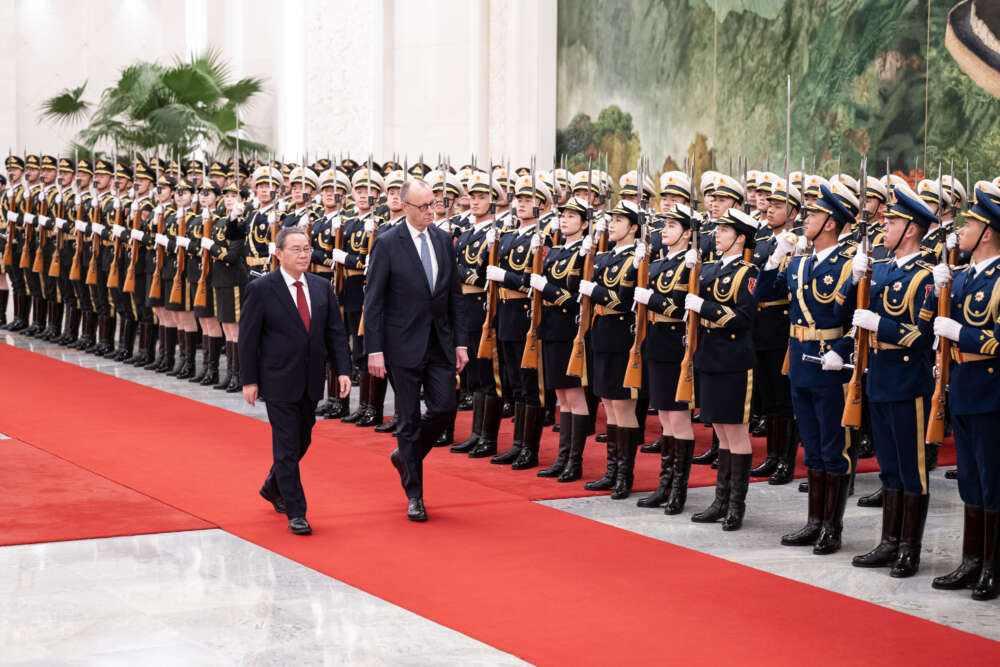

The new Greens are hawkish on human rights and the rule of law. They have been forceful in their attacks on Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s self-styled “illiberal state” project at the heart of the EU. They have also positioned themselves forcefully against authoritarian great powers. Norbert Röttgen, the CDU chairman of the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee, is right to say that “the Greens have the clearest stance of all the parties on China and Russia.”

The Greens’ growing support for transatlantic agendas is in part an alternative to “China’s authoritarian pursuit of hegemony.” The party opposed the EU’s recently-concluded Comprehensive Investment Agreement (CAI) with Beijing and seeks to block Huawei’s participation in Europe’s switch to 5G communications. Longtime Green MP Jürgen Trittin — a former minister who advocates European equidistance between China and the US — gets little traction within the party these days. That attention now goes to Reinhard Bütikofer, an MEP one of Europe’s most prominent critics of the Chinese Communist Party.

The party has been notably skeptical too toward the Kremlin, opposing the Nord Stream2 pipeline project, which the leadership of both the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats have supported.

The Greens are still the Greens, though. On military and security policy, the Green left wing is still going strong. The Greens’ election platform opposes the 2 percent defense spending goal Germany is committed to within NATO, terming it “arbitrary.”

The party does commit to “securely” funding German armed forces. But faced with hard choices amid a post-COVID budget squeeze, Green ministers would be unlikely to argue for higher military spending over, for example, investment in carbon-neutral and digital transformation, or social welfare programs — particularly with the party promising those in its election manifesto.

Once in government, the Greens may usher in the end of the Franco-German fighter jet, a key project of French-German defense cooperation. Baerbock is on record demanding Germany sign the Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty, pulling out of NATO’s nuclear sharing programs, and withdrawing all US nuclear weapons from German soil. She has not repudiated these positions since stating them three years ago. This is also a nod to the many Green party activists passionate about “feminist foreign policy” who set nuclear deterrence as an expression of “toxic masculinity” that needs to be overcome.

But while a coalition between the Christian Democrats and the Greens might not give international commentators the policy they’re expecting, the contest between Baerbock and the Christian Democratic candidate Armin Laschet will hopefully provide Germany with the foreign and security policy debate it needs.

Laschet strongly supports the NATO 2 percent goal and he believes in nuclear deterrence. He’s well placed to press Baerbock on how exactly she squares the Green party’s acute awareness of the threats posed by both the Kremlin and Beijing, with its security and military policy stance.

For her part, Baerbock can press Laschet on arms control and disarmament, as well as on his party’s weak stance on Nord Stream2 — and perhaps on chumminess with lobbyists acting on behalf of authoritarian governments, and the need for a very different China policy than the one carried out under Chancellor Angela Merkel.

And maybe a moderator in these debates will press both Baerbock and Laschet on how Germany and Europe should prepare for the day on which the US decides to no longer guarantee Europe’s security with nuclear weapons.

After 16 years in opposition, the Greens now have some of Germany’s best voices on foreign policy, and they have no shortage of ideas. But on the core of security policy, they are fundamentally out of step with Germany’s key allies.

This commentary was originally published in Politico Europe on April 23, 2021.