Competitive Cooperation: How to Think About Strengthening Multilateralism

“Multilateralism is under fire precisely when we need it most”, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said at the UN General Assembly debate in September of 2018. In many ways, this statement rings even truer two years later as the world confronts a pandemic on top of the climate crisis and protracted conflicts with a huge toll on civilians such as the Syrian war. Multilateralism faces severe challenges during the UN’s 75th birthday year and beyond. That is what most can agree on. Hardly anyone would claim that multilateralism is in great shape. But things get a lot murkier when it comes to what this crisis is exactly about, what has caused it and how we should think about improving the status quo. There is no shortage of papers on “XYZ should happen in order to have better multilateralism.”

This paper asks, “how should we think about the crisis of multilateralism and what can we possibly do about it?” It is a think piece, not a fine-grained policy paper. It seeks to complement and put in perspective the many often more fine-grained policy papers on fixing multilateralism that have come out recently. The level of ambition of this paper is different. It takes a step back. First, it seeks to sensitize for ways in which we should not think about the crisis of multilateralism for there are a number of misguided lenses in the broader public discussion. Second, it introduces a segmentation of multilateralism into four distinct “circles of multilateralism”: like-minded democratic multilateralism; like-minded authoritarian multilateralism sponsored by China and partly Russia; (near) universal diplomatic for a multilateralism and global public goods multilateralism. Third, it offers the principle of “competitive cooperation” as one way to approach thinking about how to realistically improve multilateralism in this constellation. Fourth, it briefly introduces some thoughts on how to implement this principle in each of the four spheres.

This paper is written from the perspective of democratic middle powers, with a preference for human rights and international law. Middle powers are a special breed in multilateralism. On the one hand, they have a lot at stake in terms of the health of multilateralism, a lot more at least than great powers that can much more afford a “might is right” attitude – or as German chancellor Merkel put it, rely on the “rule of the stronger” (Recht des Stärkeren) instead of the “rule of law” (Herrschaft des Rechts). Therefore, they have a strong incentive to invest in multilateral institutions since they generally see them as serving their interests. That interest they share with smaller states. On the other hand, middle powers also have significant ability to invest in multilateralism, an ability that is stronger than that of smaller governments. They can do agenda-setting, start new initiatives, defend rules and laws against attacks, mobilize support for global public goods. Middle powers have a particular responsibility to invest in strengthening multilateralism from which they have profited over the past decades. For simplicity’s sake, I use Gareth Evans’ understanding of a middle power:

‘Middle powers’ are best described as simply those states which, objectively, are not economically or militarily big or strong enough, either in their own regions or the wider world, to impose their policy preferences on anyone else – but which are nonetheless sufficiently capable, credible and motivated to be able to make an impact on international relations. What to me matters most in identifying middle powers is not in fact, for reasons I will explain, any objective measure of size – of GDP, population, landmass or anything else – but rather the effectiveness with which they practice what I describe as ‘middle power diplomacy’.

The latter criterion (diplomatic effectiveness) makes a country like Norway that has outsized influence in multilateral diplomacy a middle power that may not otherwise have been considered a middle power. The criterion of diplomatic effectiveness (more than other capabilities listed in Evans’ definition) are subject to changes depending on the government in charge. There is a case to be made that authoritarian, nationalist or populist turns can decrease the influence of middle powers in the international system. For example, Brazil under Bolsonaro is a less effective diplomatic player than Brazil under Lula or Dilma Rousseff.

Misguided Narratives: How (Not) to Talk About the Crisis of Multilateralism

Myth 1: It’s Multilateralism’s Fault.

A 2020 report by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) written by the Economist Intelligence Unit claims that “multilateralism has broken its promise to the world’s most vulnerable”. This assertion is based on the record of providing public goods to the world’s neediest during the current coronavirus pandemic. While there is much to be said about the shortcomings of the global coronavirus response, making “multilateralism” responsible does not advance the debate. As Richard Gowan points out, “saying that ‘multilateralism’ has broken a promise is misleading, and lets actual culprits off the hook. States and international organizations have screwed up. You can’t just blame the ‘ism’”.

Multilateralism is no actor that can be held responsible. In John Ruggie’s seminal definition, “multilateralism refers to coordinating relations among three or more states in accordance with certain principles.”

Today we would add “and non-state actors” into the definition. This makes clear that multilateralism is a practice by state and possibly non-state actors, not an actor in its own right. States are the principals of multilateralism and therefore should be held accountable for outcomes. If states choose to create agents in the form of international bureaucracies (e.g. secretariats for multilateral bodies) then those can also be held accountable for outcomes. “Don’t blame it on the ‘ism’” also applies the other way around in terms of making the case for multilateralism. While especially for democratic middle powers it is possible to make a principled general case that multilateralism is more desirable than the alternatives unilateralism and bilateralism, it is dangerous to limit the advocacy for multilateralism to this. From a sheer language perspective, “multilateralism” is a tough sell. It is an unwieldy term and to many has the “ring of a prescription drug” as German foreign minister Heiko Maas once put it in a late-night discussion program on German TV. Promoting multilateralism as an end in itself certainly is not a winning proposition with the general public, parts of which even in a country like Germany have recently become more skeptical (as evidenced in the debate on the Global Pact on Migration). So it is all the more important to make a concrete case what specific instances of applying multilateralism can achieve to address a key problem and what investments are necessary for multilateral arrangements to work in a particular field (see the recommendations by the Annual Policy Dialogue’s three Working Groups on sustainability, digitalization and social justice and inclusion).

Myth 2: A New US President Will Fix Multilateralism.

For sure, US president Donald Trump’s “America First” approach has created significant damage to multilateral bodies on all fronts. It was the shock of Trump’s victory that prompted German foreign minister Heiko Maas to start the “Alliance for Multilateralism” with like-minded middle powers such as Canada and France.

Still, banking on a change in the White House as the fix to multilateralism’s problems is an ill-considered bet. That is not just because Trump against the odds might still pull off a surprise victory in November. Even if Joe Biden becomes the next US president, this will not become the game changer fixing multilateralism’s problems that some may hope for. On a number of fronts (as will be discussed in greater detail below) a Biden victory does offer opportunities for strengthening multilateral bodies. But the work of the “Alliance for Multilateralism” will not be completed single-handedly just because Trump is no longer US president. The US can no longer play the role it played post-1945 in terms of the creation of the post-war multilateral order.

For that post-1945 order, John Ruggie is right to argue that, “when we look more closely at the post-World War II situation, (…) we find that it was less the fact of American hegemony that accounts for the explosion of multilateral arrangements than it was the fact of American hegemony.”

Stephen Wertheim retraces in his new book “Tomorrow, the World. The Birth of US Global Supremacy”, that US investment in multilateral institutions was not for completely altruistic reasons. Wertheim calls it “instrumental internationalism”. It served to underwrite and sell back home in the US the new US role as global hegemon. At the same time, this did allow for the creation and maintenance of a wide variation of multilateral bodies. And US exceptionalism notwithstanding, that great power multilateral exceptionalism of the US had positive effects on the multilateral system. In Europe for example it allowed for the creation of the European Union that helped to pacify the continent. And despite the severe failures of the Washington Consensus, the US underwriting the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund as stabilizing institutions helped to stabilize the economic and financial system after the Second World War.

A Biden victory will not easily get us back to that unique role of pro-multilateral US hegemony, at least not in terms of a longer-term stable equilibrium. James Goldgeier and Bruce Jentleson make a very persuasive case for why this is in a recent piece in Foreign Affairs.

“If we think of politics as we do monetary currencies — measuring stability by fluctuations within an equilibrium zone — why should the United States’ friends trust that even if Trump loses the 2020 election, American politics will stay within that political equilibrium zone for long? Instead, even close allies will have to hedge their bets, in case the United States shifts yet again in the following presidential election or even after the 2022 midterms.”

The US may rejoin the Paris agreement on climate change under Biden but leave it again under his successor. Democratic middle powers should take maximum advantage of a positive multilateral agenda they can pursue together with a President Biden. Rather than passively wait for whatever agenda the new US president proposes, they should approach the US administration with their own agenda on what to push for together. That way democratic middle powers can capitalize on the opportunity that a change in the White House offers. At the same time, they should continue to engage with key members of the US Congress which plays an important role in crucial aspects of multilateralism. They should, however, continue with formats such as the Alliance for Multilateralism. Regardless of who is in the White House, multilateralism can profit from that extra push in all three baskets of activity of the Alliance for Multilateralism: defending international norms when attacked, providing impetus for reforming multilateral institutions and pushing for new approaches to underregulated areas. At the same time, formats like the Alliance for Multilateralism offer a hedge for when things turn sour again with a more nationalist-reckless US administration.

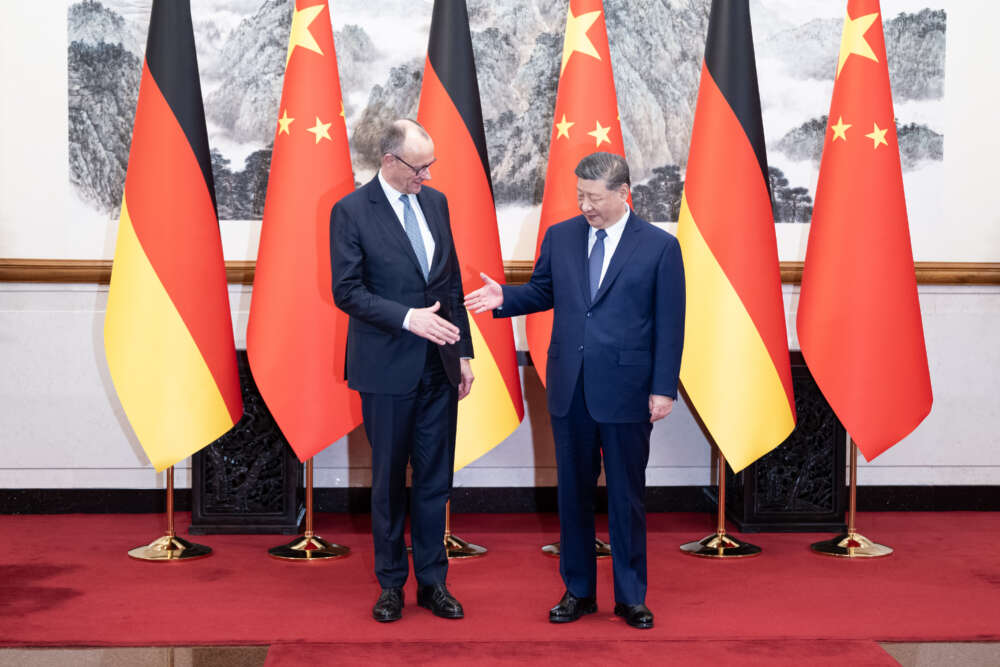

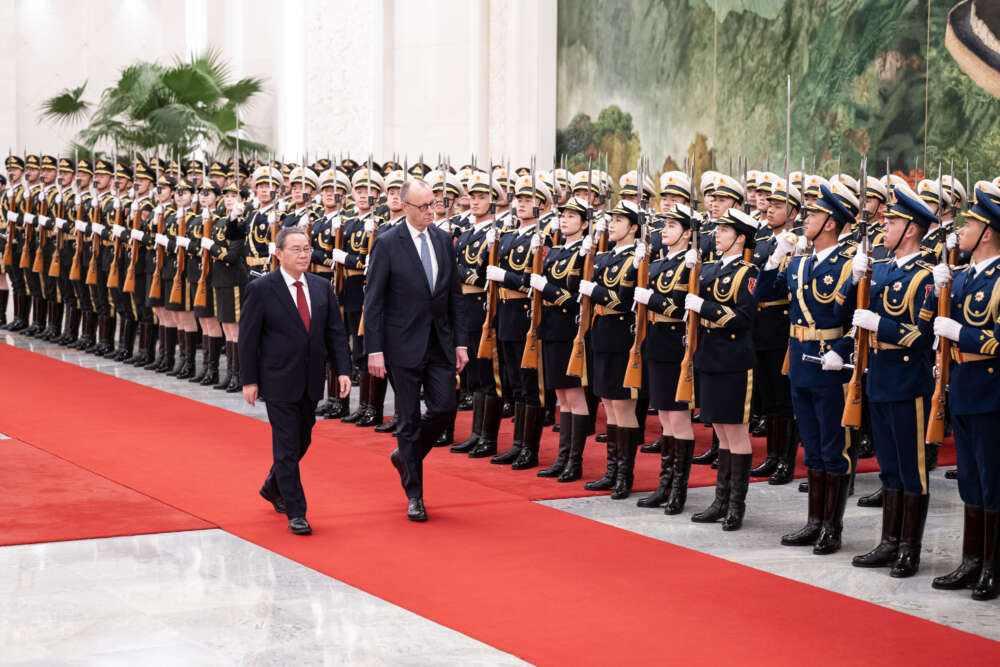

Myth 3: China Will Fix It.

In his Davos speech in 2017, Chairman Xi sought to convince the world that Beijing is the new champion of multilateralism — a reliable counterweight to reckless US unilateralism under Trump. Wherever possible, democratic middle powers should take Beijing by its word and demand concrete action to support multilateral initiatives, from new arms control treaties to action on the climate crisis (such as taking concrete steps toward the carbon neutrality by 2060 pledge that Chairman Xi has offered). But they should not have any illusions this will bear a lot of fruit. As EU High Representative Borrell has argued, in reality Beijing pursues a “selective multilateralism that wants, and is based on, a different understanding of the international order”.

This statement is a reflection that Beijing’s approach prioritizes its very own set of values negating universal human rights and a rules-based international order. The Chinese party-state seeks to counter any effort to hold it to account for violating human rights (such as through treatment of minorities or opposition voices within China and Hong Kong) or international law obligations (such as in the South China Sea). It builds coalitions of like-minded authoritarians and not so like-minded but easily bought off states in multilateral bodies to shield itself against criticism of the treatment of Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities. And as Katrin Kinzelbach details Beijing seeks to “launch a new global narrative that seeks to displace human rights”, implanting Chairman Xi’s vision of a “Community with Shared Future for Mankind” into numerous UN resolutions. And Beijing’s signature international project, the Belt and Road Initiative, is a series of bilateral arrangements with countries in multilateral draping.

As Nadège Rolland points out,

“Chinese leadership’s efforts to increase China’s discourse power should not be dismissed or misconstrued as mere propaganda or empty slogans. Rather, they should be seen as evidence of the leadership’s determination to alter the norms that underpin existing institutions and put in place the building blocks of a new international system coveted by the Chinese Communist Party.”

Myth 4: A Club of Democracies Can Fix It.

Under a President Biden there will be a renewed push for democracies working together more effectively. Democratic middle powers should welcome and harness this. A “Democratic 10” (D‑10) made up of the G7 members (including EU) plus Australia, India and South Korea is a good format to better coordinate multilateral policies among the world’s strongest democratic economies. The D‑10 idea (which has already been implemented at the track 1.5 level involving think tanks and policy planners) has recently also received support from the UK government. And a planned Biden “Global Summit for Democracy” (more on that below) is a good idea. But reviving the idea (fostered during the heady neoconservative days of the George W. Bush administration) that a new forum bringing together the world’s democracies could be an alternative to the United Nations is counterproductive. Precisely because we need to deal with conflicts diplomatically, we have universal membership bodies such as the United Nations. And to address truly transnational challenges such as climate change or pandemics you need both democracies and non-democracies at the table.

Myth 5: Public-Private Cooperation is the New Multilateralism and the Answer.

Public-private partnerships can make an important contribution to multilateralism. But unlike some today want to make us believe they are not exactly new. In the late 1990s we had a wave of thinking about global public policy networks and public-private partnerships. Some of these partnerships and networks have been able to make a positive difference, especially in global public health. Take the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) or the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) both of which have played a very constructive role in dealing with the current coronavirus pandemic. It is important to make use of these innovative approaches to multilateralism and find out if they can prove to make a positive difference. But over the past two decades they have not been able to influence the broader trajectory of multilateral policy-making which has been very much, among other factors, influenced by renewed great power geopolitical conflicts and a nationalist-sovereigntist backlash in a number of key countries. Public-private partnerships can complement efforts of states in often meaningful and important ways. Non-governmental organizations and businesses can bring important resources to the table, including expertise, perspectives from affected groups as well as money. It is for the principal actors of multilateral action, states, to define constructive ways to consult non-state actors in norm-setting processes where useful and appropriate. And public-private partnerships, if managed appropriately, can contribute to providing global public goods in areas such as global public health.

Myth 6: The Old West Alone Can Revive Multilateralism.

Many initiatives to revive multilateralism are put forward by countries of the “Old West”. But to succeed in today’s environment, efforts need to break out of this old club and include key players such as India, Brazil, Mexico as well as key Asian and African middle powers. There is a wealth of experience with multilateralism in Africa, Latin America and across Asia, from the African Union to ASEAN. Global efforts to revive multilateralism should draw on this rich experience.

Middle powers also need to reach out to smaller countries and offer themselves as credible partners for these smaller countries taking their concerns seriously and integrating them into their agendas. The majority of states are neither great nor middle powers. And at the UN to a significant extent politics is a numbers game, something that Beijing has very much realized when mobilizing supporters for its causes.

Smaller, non-Western states do no longer want to be merely the recipients of rules that were made by others. They want to have a stronger voice; better representation and they want to be co-shapers of rules. And Western states are well advised to make room for this.

Therefore, established Western middle powers also need to be credible advocates of reforming international bodies to reflect new power realities instead of clinging to overcome privileges. The European Union desperately clinging to the IMF top job is a very sad story in this regard and fundamentally undermines European credibility on this front. It is equally sad to see the US clinging to the World Bank presidency. That EU members decided not to put forward a candidate for the WTO top job in 2020 and instead chose to support highly qualified candidates from historically underrepresented regions (Africa and Asia) was a step in the right direction.

Myth 7: There Is a Single“Liberal International Order” to Defend.

For some in the West, multilateralism is about defending the “liberal international order”, a term that US researcher John Ikenberry coined in the 1990s. Many of today’s politicians in the West also use the phrase, but it is misleading. Champions of the concept tend to forget that the liberal international order during the Cold War was very much a bounded order. NATO, GATT, the OECD, the G7 and company were reserved for the Western club, while the Eastern bloc relied on its own institutions (such as the Warsaw Pact and COMECON). In addition, there were global multilateral institutions like the UN in which states struggled for order amid fierce competition.

For some time after 1989, the West was able to indulge in the vision that the bounded liberal order of the Cold War could globalize and become a universal “liberal international order”. Multilateralism was meant to be the core of a“new world order” beyond the great power rivalries (the idea of George Bush senior’s “New World Order”). Today, with the benefit of hindsight, we know that this was a pipe dream. Those calling the shots in Beijing and the Kremlin have decided they will not confine themselves into such an architecture any more than the Soviet Union was part of a “liberal international order” during the Cold War. Perhaps the central fallacy of the approach of globalizing the “liberal international order” was the assumption that China and others had every incentive to quietly “socialize” into a world order shaped by the West in which the West has a monopoly to decide what being a “responsible stakeholder” means. Beijing for one concluded that it would pursue a dual strategy of using its power to shape existing global institutions in its interest (going against universal values such as human rights as well as international law) while at the same time starting new parallel Sino-Centric organizations such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank or (together with Russia) the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Today, it has become clear that great power conflicts (especially between the US and China) are again a central framework constraining multilateralism. This also has an ideological dimension that many had thought was overcome with the demise of communism in 1989. Today, again there is a competition of systems between democracy and authoritarianism – but this time around with a high-tech authoritarian state capitalism that unlike during the Cold War is deeply embedded in the economic and technological systems of democracies.

All this means we can safely put the hopes for globalizing the “liberal international order” to rest for the foreseeable future. And rather than continuing to pretend that there is a single global “liberal international order” to defend, policymakers from democracies should base their approaches on a realistic assessment of the fragmented nature of today’s multilateral order.

How to Think About a Fragmented International Order: Four Circles of Multilateralism

Identifying and distinguishing between four circles of multilateralism can provide such a realistic depiction of the multilateral order. These circles are distinct because of the membership of the multilateral arrangements in these circles and the functions these arrangements fulfill.

The first circle encompasses the multilateral bodies orchestrating cooperation based on shared democratic or market economy principles (such as the OECD, NATO or G7). These are limited membership organizations, partly of regional or inter-regional nature. The Western core of these institutions of the like-minded is what constituted the “liberal international order” as a bounded order during the Cold War. Membership in these organizations is based on clear criteria. In the case of the OECD, members need to be democratic societies committed to the rule of law and protection of human rights and free-market economies. These can also be regional or sub-regional organizations, such as ECOWAS which has the “promotion and consolidation of a democratic system of governance in each member state” as key principle. For these organizations, democratic backsliding of one or several of their members constitutes a credibility problem.

The second circle involves multilateral bodies initiated by non-democracies, chiefly China and Russia. From the perspective of Western powers, these organizations have been described as “parallel institutions”. Already in 2007, Nazneen Barma, Ely Ratner and Steven Weber predicted the emergence of a “World Without the West”, the effort of emerging non-Western powers to “route around” institutions dominated by the US and “deepening ties among themselves in economic, political, and even security domains”. This has come to pass in the past decade. Membership in these multilateral efforts is not based on clear criteria in terms of the domestic make-up. These are not necessarily institutions of like-minded authoritarians. One prominent effort, the BRICS grouping, brings together Brazil, India, China, Russia and South Africa, a mix of democracies and non-democracies. What united the BRICS grouping was the counter-hegemonic impulse against the dominance of the US and the West and their own exclusive groupings such as the G7. This counter-hegemonic unity impulse is becoming less strong within BRICS the more powerful China becomes and the more some BRICS members such as India see China’s hegemonic aspirations as a threat.

Most prominent among the “parallel institutions” are clearly Beijing-centric efforts such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). An effort in the security realm co-led by China and Russia is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Another Russian-centric effort is the Eurasian Economic Union.

The third circle involves multilateral bodies with diverse and/or (near) universal membership. This includes various United Nations bodies as well as international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank. This is where most of the formalized diplomatic competition on international norms takes place. A particular case is the World Trade Organization (WTO) that was created for cooperation between industrialized countries – and for their interaction with emerging economies. However, the WTO was not designed for the membership of a large and economically strong authoritarian state-capitalist country such as China that at the same time claims developing country benefits. This has undermined the belief of the US and increasingly also other actors (such as the EU) that the challenges China poses can be adequately dealt with within the WTO framework that was not conceived for that.

The fourth circle comprises multilateral initiatives dealing with global public goods or global commons. These bring together a similarly diverse range of democracies and non-democracies as institutions in the third circle. But the functional area makes the fourth circle distinct: the imperative of cooperation is stronger and more evident with regard to global public goods than as regards other diplomatic fora. That is not to say that geopolitical rivalries and ideological differences do not play a role in institutions dealing with global public goods (recent experience with fighting the coronavirus pandemic clearly demonstrates this). But they tend to be less prominent than in other fora. Another distinct feature of this circle is the stronger importance of public-private formats and networks involving NGOs, philanthropies and business. It is important to stress that my understanding of global public goods or global commons is limited to problems that are global and transboundary by nature, not by choice. This means this area includes efforts to deal with the climate crisis, pandemics and global commons such as the oceans. It excludes trade, finance and technology. The latter are areas that can be global and transboundary by choice, but they can easily be re-designed to exclude others. The current debate on US “decoupling” from China illustrates this. In this context, it is important for democratic middle powers to come to terms with “weaponized interdependence”, the use of technological, financial and economic (inter)dependencies to coerce other players.

As Amrita Narlikar points out, it is key for democratic middle powers “to have some difficult conversations with their own electorates and with allies on the countries that they trust enough to not misuse economic ties for geostrategic purposes.” That means making conscious choices on technological or financial (inter)dependence, which unlike interdependence on pandemics and climate change is interdependence by choice and design and not interdependence that is functionally given and unchangeable.

The Imperative of Competitive Cooperation

Competitive cooperation is the imperative for democratic middle powers navigating these four circles. This principle brings together two of the key conditions democratic middle powers face: First, a competition of systems, chiefly with Beijing’s authoritarian state capitalism. Second, the need to cooperate on truly transboundary challenges such as climate change and pandemics as well as the need to have functioning global fora to negotiate differences. So democratic middle powers need to compete and cooperate at the same time. They need to cooperate with like-minded players in circle 1 to be competitive in the competition of systems playing out with parallel institutions (circle 2) and in universal membership institutions (circle 3). They also need to seek to shore up global institutions and cooperate with non-like-minded countries on global public goods in circle 4.

Circle 1: Coordination Among Like-Minded Democracies

Competitive cooperation means first of all strengthening the competitive base: the trust and credibility of democracies. Many democracies from the US, Europe to India deal with authoritarian tendencies at home. Fighting them is the only way they can be credible players. Similarly, organizations of like-minded democracies such as the European Union need to find ways to effectively deal with authoritarian governments in their midst (such as Hungary). Under a President Joe Biden the US could revert to playing a constructive role on bringing like-minded democracies together. Earlier this year, Biden pledged:

“During my first year in office, the United States will organize and host a global Summit for Democracy to renew the spirit and shared purpose of the nations of the free world. It will bring together the world’s democracies to strengthen our democratic institutions, honestly confront nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda.”

Biden said he would seek to galvanize “significant new country commitments in three areas: fighting corruption, defending against authoritarianism, and advancing human rights in their own nations and abroad”. He further stated that “as a summit commitment of the United States, I will issue a presidential policy directive that establishes combating corruption as a core national security interest and democratic responsibility, and I will lead efforts internationally to bring transparency to the global financial system, go after illicit tax havens, seize stolen assets, and make it more difficult for leaders who steal from their people to hide behind anonymous front companies”. The latter point on dealing with complicity in kleptocracy on the part of major financial centers is of crucial importance.

At its core, the Alliance for Multilateralism could be a mechanism of like-minded democratic countries looking out for one another in the face of economic and political coercion. One example is Beijing’s hostage diplomacy. In December 2018, Beijing took two Canadian citizens as hostages (one of which, Michael Kovrig, is a diplomat now working for the International Crisis Group), emulating a practice embraced by the likes of the regime in Tehran. Beijing’s goal is to put pressure on Canada in the extradition case of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou. Roland Paris has powerfully argued that:

“Such behaviors by national governments are eroding important restraints on international conduct. Worse, they risk normalizing murder, kidnapping and arbitrary detention as forms of statecraft. Mid-sized powers can and should work together to counter this trend – by publicizing such events, coming to each other’s assistance when their citizens are targeted, and penalizing perpetrators when it is feasible to do so. The alternative is to stand aside as the rule of law gradually gives way to the law of the jungle – a world in which mid-sized countries would face even graver dangers.”

Similarly, middle powers such as the EU, Australia, India and others could establish a collective security mechanism against economic coercion. Another suggestion is for democratic (middle) powers to form a technology alliance to better engage in global technology competition and set norms and standards. This is a reaction to the growing clout of China in this area. As Richard Gowan argues in a paper with Anthony Dworkin, new digital technologies (“cyber”, “artificial intelligence”) is an area in which middle powers in isolation do not carry much weight but can make a difference if they coordinate. Democratic middle powers need to be mindful that many countries simply want access to reliable and affordable technology. For many, it is a secondary concern whether they make themselves dependent on Chinese, US, Japanese, European or other technology. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that democratic countries such as different EU members and the US are competing with one another on the technology front and that discussions in Europe about “technological sovereignty” and industrial policy are also very much motivated by reducing dependence on the US and competing with US technology leaders.

Circle 2: Competing with“Parallel Institutions”

The emergence of “parallel” multilateral bodies should be nothing surprising to those who have traditionally called the shots. It was only natural that unchallenged US hegemony after the end of the Cold War would provoke a banding together of those unhappy with that state of affairs. That led to the birth of the BRICS. Equally, it should not come as a surprise that authoritarian great powers like to start their own multilateral bodies. This was the case with the Soviet Union. This is now the case with China and Russia. That is why there is no reason to react overly bitter or surprised about Beijing’s move to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or the joint venture with Moscow on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Democratic middle powers should try to shape these bodies in a productive direction where this seems like a realistic option. In the case of the AIIB it was the choice on the part of European middle powers and others to come on board and try to co-shape the new institution to adhere to good governance standards. They should now review the record of how well they have been able to achieve that goal and draw lessons from that. More often than not, trying to shape these institutions will not be the sensible option. The better approach is to be competitive and be sure to push against harmful initiatives from these parallel institutions and most of all offer better alternatives for third countries through other means. One example is the Connectivity Strategy of the European Union that seeks to provide an alternative to Chinese Belt and Road financing. Democratic middle powers should take care not to add legitimacy to ventures like the Belt and Road Initiative by signing memoranda of understanding.

Circle 3: Competing and Cooperating in Universal Membership Bodies

Democratic middle powers need to lead the effort to strengthen and reform multilateral bodies with (near) universal membership.

All democratic middle powers need to put their money where their mouth is and increase the predictability of funding for the UN system. As champions of multilateralism, democratic middle powers should proudly be the first line to pay their contributions to UN on time while others are often dragging their feet. If you are a champion of multilateralism, you should increase predictability of funding for UN agencies by increasing the share of core budget compared to discretionary funding for specific activities. And if you are a champion of multilateralism you should channel more of your funding supporting the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development through multilateral rather than bilateral channels. Democratic middle powers could support the Funding Compact as a mechanism that combines commitments on the part of member states for better funding with commitments on the part of UN agencies for better transparency, accountability and effectiveness. The reason for this is simple: the UN system can only be an effective forum for diplomacy and an effective implementer of commonly agreed goals if it is properly funded and better run.

At the same time, democratic middle powers should better coordinate to protect universal human rights, also in UN bodies where human rights abusers stand together and try to win over third countries (such as China trying to shield itself against criticism of its treatment of minorities or Saudi-Arabia seeking to justify its human rights record). Nicole Deitelhoff argues that “a key characteristic of the present crisis is not the lack of multilateral rules but that fewer and fewer states feel bound by them”, such as is the case in international humanitarian law (IHL). The Syrian war is a sad illustration of this. Democratic middle powers should reinforce cooperation to push back against violations of IHL.

Circle 4: Pushing for Cooperation on Global Commons

From the perspective of democratic middle powers, there is the need to enable international bodies to provide public goods and deal with truly transboundary challenges that regularly outpace and outcompete efforts to address them. This is precisely the opposite of what the Trump administration has done. This means investing in a better World Health Organization instead of running away from it. It means strengthening international agreements on dealing with the climate crisis instead of undermining them. It also means negotiating with geopolitical competitors to explore cooperation on these global public goods such as controlling pandemics and the climate crisis.

The coronavirus pandemic clearly illustrates the strains on the multilateral system. As Richard Gowan writes:

“It is hard to harness multilateralism to productive ends if the US and China frame global affairs as zero-sum competition. The two powers’ response to the COVID crisis has shown they can exploit and undermine multilateral organizations in their contest for global influence. The pandemic has at least done other states the service of illustrating how fragile some international institutions will be in period of major power competition.”

Indeed: Neither of the great powers (US and China) has played a constructive leadership role in the global handling of the pandemic. Multilateral bodies such as the World Health Organization have become sites of great power rivalry and they have a hard time navigating this. This (mis)handling of the pandemic by the US and China is demonstrating both, the need for and the success of middle power engagement. The need for global cooperation is illustrated very clearly by the pandemic in terms of both preparedness and reaction. Middle powers played a constructive role at the WHO and filled financial gaps. The EU and others contributed to funding for multilateral vaccine initiatives such as CEPI. The Alliance for Multilateralism strengthened the commitment to make vaccines available for all. Private philanthropic players contributed significantly. Public-private partnerships such as GAVI, CEPI have demonstrated their value added in the crisis.

This shows that democratic middle powers can indeed make an important contribution to strengthen global commons multilateralism despite great power rivalries. And it is here where a new US administration that is open again to global cooperation on climate change and pandemics could make perhaps the biggest difference. With a Biden administration, democratic middle powers could take crucial steps together on global public goods multilateralism. And they could make sure to constructively engage Beijing on both pandemics and the climate crisis and hold Beijing to account on its multilateral promises on distributing vaccines through the COVAX facility and reducing carbon emissions. Ideally, as Oliver Stuenkel has argued, democratic middle powers, the US and China also work together to incentivize the Brazilian government to stop Amazon deforestation.

Amrita Narlikar has written about “well-intentioned leaders” muttering “dull platitudes on multilateralism, motherhood and apple pie.” In order to improve the current state of multilateralism it is crucial to move beyond the feel-good rhetoric on multilateralism. Democratic middle powers can and must do both: strengthen their cooperation in global competition of systems and strengthen cooperation to stabilize and reform multilateral bodies involving both democracies and non-democracies.

This commentary was published on October 28, 2020 as part of the 2020 Annual Policy Dialogue “Multilateralism that Delivers” in cooperation with the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the World Leadership Alliance-Club de Madrid.

The author would like to thank the members of the Bertelsmann Stiftung, Club de Madrid and GPPi teams as well as the members of the review group convened by the Bertelsmann Stiftung for extremely helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. The author would also like to thank Julian Philippi for research support as well the team at the Foreign Policy Planning staff for very helpful conversations in the context of a joint project on multilateralism. All opinions and positions in this paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the participating organizations or members of the review group.